How long we will need to wait for the final aria I can't and won't predict, but to place our current peril into perspective, I'd like to take you for a trip down a memory-holed lane. Back to December 5, 1996. For reference, the Nasdaq on that day was 1287.

Alan Greenspan, then chairman of the US Federal Reserve, gave his now-famous speech, posing the question: "How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values?"

It was an odd question, given that the exuberance was fuelled by the Fed chairman himself. For several years, Greenspan had been running interest rates around 4 per cent, while inflation hovered just below 3. This was well below the historical norm and was driving punters into increasingly speculative investments.

Pets.com came to symbolise this era: a badly run firm with a history of losses that spent far more on branding than it ever gained in revenue, yet the market embraced it with the enthusiasm my labrador has for leftover bacon.

Anything with a tangential link to the internet was drawing in cash, and by March 2000 the Nasdaq was a few kilobytes over 5000. Then, pop, the dotcom bubble burst, the Nasdaq fell and the global economy spluttered. This was over three years after Greenspan had warned the market, and the Nasdaq had nearly tripled in that time.

In hindsight, Pets.com and many of the other narrative- rather than profit-driven firms were always doomed to collapse, but something had to be the slap to bring mass hysteria to a close.

The dotcom recession wasn't unexpected. One contemporary and highly regarded economic writer, James Grant, wrote in his 1996 book The Trouble with Prosperity: "Predictably, the risks to saving are the greatest just when they appear to be the smallest. By suppressing crises, the modern financial welfare state has inadvertently promoted speculation. Never before has a boom ended except in crisis."

The trouble with permabears such as Grant is that they predict more recessions than occur. I am in that category. By nature and inclination, I am constantly looking for and finding evidence of the upcoming economic collapse.

Today the Nasdaq sits at over 15,000. That seems absurd to me, but I would have said that at 9000. A canny speculator could have made a lot of money ignoring my opinions.

So, bare this in mind as I outline why I think we are charging headlong towards an economic catastrophe that will make this pandemic seem like a runny nose.

Let's start with cheap money. For over 12 years we have had interest rates running at a fraction above inflation, as the Americans had for only five years before the dotcom crash.

Currently, rates are lower than inflation; a dangerous inflection point. Equities have ballooned. The NXZ50 has exploded from its post-GFC slump of 2500 to over 13,000 today.

During these economically unremarkable 13 years, our GDP hasn't even doubled. We have seen an even more extreme acceleration in property prices as Boomers facing retirement are throwing their saving at anything that promises a return.

Comment: In the US and UK property prices are soaring in part because investment giants and banks are buying up the rental market, with prices 30% higher than before the financial crash of 2008; which, lest we forget, was preceded by an unprecedented housing bubble and partly driven by endemic fraud in the property market.

If you think there is any connection between today's financial market and reality, may I remind you that Dogecoin has a market cap of US$38 billion. We have entered the tulip phase of the cycle.

The destruction of a safe haven for savers not only fuels reckless investment, it stimulates reckless borrowing. The most terrifying data maintained by the Reserve Bank, other than the transcripts of Adrian Orr's speeches, is our level of household debt to disposable income, and the cost of servicing that debt.

Just before the GFC, our average level of household debt, including mortgages, credit cards and student loans, was 158 per cent of the average household income. It was only 100 per cent in 2000. It fell slightly in the following years, but it is now soaring northwards.

Comment: Following the banking crash, governments - despite advice to the contrary - slashed public spending whilst they also pilfered the public purse to pump billions into the failed banks claiming that it was critical to keep economies afloat. This inevitably caused economies to slide, inflation to rise, wages to stagnate, unemployment and underemployment to rise, which, taken together meant it cost people a lot more just to maintain the same living standards. And now we have to factor in 17-plus months of rolling lockdowns.

According to our central bank, this now sits at 167 per cent, and this debt level is growing at an alarming rate, jumping by 2.6 per cent in the March quarter. We are taking on higher level of debts thanks to the massive loans required to enter the housing market.

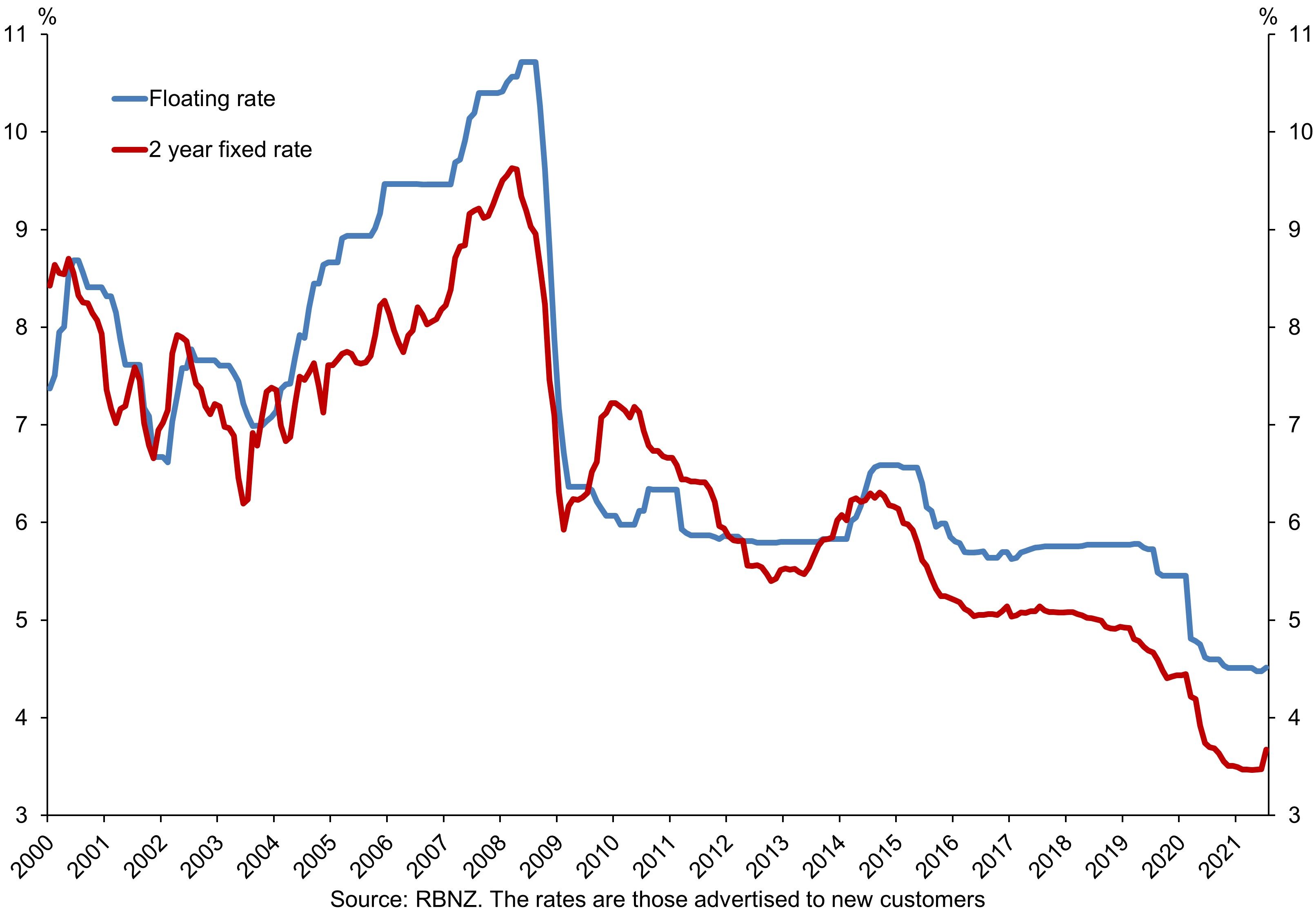

The reason all of this continues to work is that the cost of servicing these freighting levels is falling. We are taking on more debt and, at least in interest, it is costing less to do so thanks to near-zero interest rates.

When rates rise, there is going to be some severe economic heartburn as servicing costs quickly consume household budgets. Even respectable households will face a choice between meeting the mortgage payments and maintaining Ethan and Jemima in their private schools.

A 1 per cent increase in a million-dollar mortgage is $200 a week, and interest rates could increase by a lot more than that. They were 10 per cent in 2007 and inflation wasn't much higher than it is today.

The inevitable rise in rates will cause asset and equity prices to fall, causing panic and fear. Investment will fall as higher rates makes projects less profitable and many highly leveraged firms will fail.

We have run loose monetary policies for over a decade, printed a sixth of our GDP in new cash, and are currently forcing most of the workforce to be unproductive while borrowing money to give to firms to prevent them from collapsing.

This cannot continue. It will not continue. The only path forward is a massive economic crash, decades of stagnation or a surge of economic growth - and we are not growing our economy sitting at home eating the last of the bread weeks before its expiry date.

Damien Grant is a business owner based in Auckland. He writes from a libertarian perspective and is a member of the Taxpayers' Union but not of any political party.

Comment: As we've seen with the globally coordinated coronavirus hysteria, it's probable that the next crash will be contrived or hijacked by these same nefarious forces with the intent to further their enforcement of the dystopian agenda: