© Bryan Anselm/New York Times

Jean Wickham's two sons are in college. Her husband has worked at the same New Jersey casino for 36 years.

She recently felt secure enough to trade her full-time casino job for two part-time gigs that came with an expectation of bigger tips.

Then the coronavirus shut down every casino in Atlantic City and instantly put more than

26,000 people out of work — 10 percent of the county's population."I've worked since I was 14 years old," said Ms. Wickham, 55, a card dealer. "We've never had to rely on anyone else."

Until now.

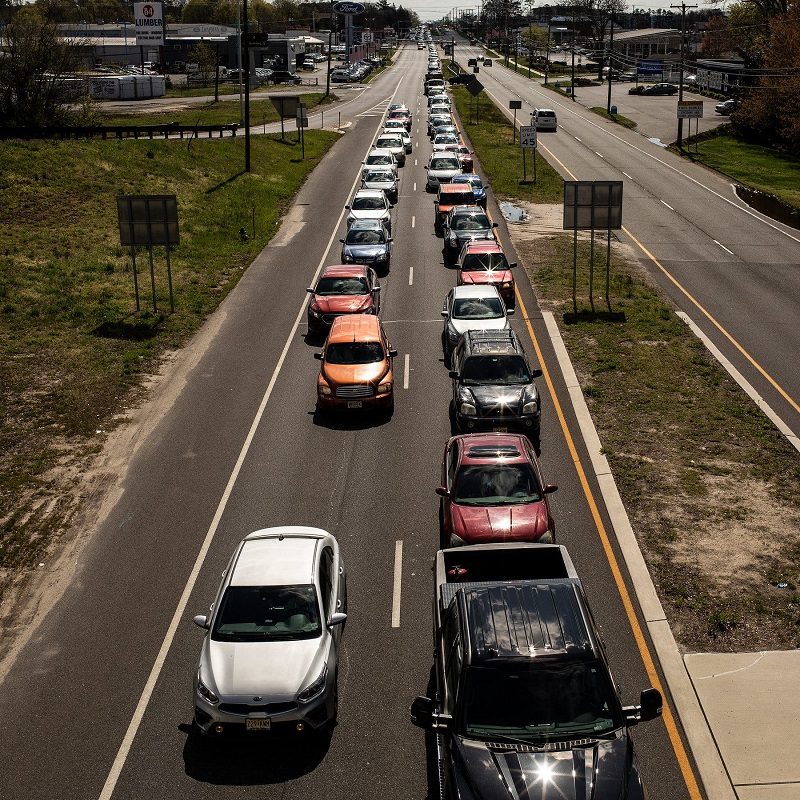

The Wickhams' minivan was one of thousands of vehicles that snaked as far as the eye could see one morning last week in Egg Harbor, N.J., 10 miles west of Atlantic City. The promise of fresh produce and a 30-pound box of canned food, pasta and rice from a food bank

drew so many cars that traffic was snarled for nearly a mile in three directions, leading to five accidents, the police said.

"I'm just afraid I'm going to lose my house," said Ms. Wickham, who lives in Egg Harbor. "I feel like a failure right now."

In more than 40 percent of households in New Jersey, at least one person is out of work because of the coronavirus pandemic, a

Monmouth University poll released on Monday found.

Many suddenly unemployed workers in one of the nation's wealthiest states say they have been pushed to the edge of hunger, forced to ask for help for the first time in their lives.

Lines at a food pantry in Summit, an affluent commuter town in northern New Jersey, stretch around the block every Tuesday evening. A food bank on the Jersey Shore has started a text service to give new users a discreet way to seek help.In Egg Harbor, the long line of Accords, Elantras, Odyssey minivans and a lone black Jaguar carried casino bartenders, poker dealers, housekeepers and cooks.

About 1,500 emergency meal kits, which provide supplemental food for a family of four for about 14 days, were distributed to casino workers by the

Community Food Bank of New Jersey in just under three hours, requiring several additional truckloads of food to be brought to the site.

Once all the meal kits were gone, many cars remained circled around the abandoned mall where the food was being handed out in the empty parking lot.Those drivers were given a five-pound bag of onions, three red cabbages and one green cabbage.Sgt. Larry Graham, who leads the Egg Harbor Township Police Department's traffic division, estimated that about

1,500 cars were turned away.

© Bryan Anselm/New York Times

The surge of need is unlike anything seen before by the Community Food Bank, the state's largest provider of emergency food, officials said, surpassing the demand that followed Hurricane Sandy and the

19-month Great Recession that ended in 2009.

The food bank's

Egg Harbor distribution center, which serves all or part of four counties in southern New Jersey, is now providing food for

2,500 families each week, up from 1,000 before the pandemic, said Kimberly Arroyo, director of agency relations and programs at the food bank."The need is just crazy," Ms. Arroyo said. "We're seeing families that we've never served before."

Last Monday,

Fulfill, a food bank that serves Monmouth and Ocean Counties, began offering a new way to help people access emergency food. Users text the words "findfood" to

888-918-2729 and are matched with the three nearest food pantries, based on ZIP code.

"This is a stigma-free service for them to get food for their families in a safe grab-and-go way, so they can spend the little money they have left on housing and co-pays" for health care, said Fulfill's chief executive, Kim Guadagno, who is New Jersey's former lieutenant governor.

Fulfill has also joined with Jersey Shore restaurants to provide 11,250 extra meals a day.Last Wednesday's food distribution for casino workers was run with help from Unite Here Local 54, the union that represents about 9,000 workers at Atlantic City's restaurants, casinos and hotels who earn an average of about $12.50 an hour, plus tips.

"As the man, I kind of have these antiquated ideas, like, I shouldn't ask for help," Richard De Angelis, 45, a poker dealer at the Golden Nugget casino, said as he popped the trunk of his car to accept food. He added, "It wasn't easy to come."

In New Jersey, considered the second-wealthiest state in the nation, a staggering 858,000 residents had filed for unemployment benefits by last Thursday, up from 84,000 for the same time period last year, Gov. Philip D. Murphy said last week.That number is likely to climb far higher. The antiquated computer system that handles

unemployment claims has been slowed by a high volume of users, and even temporarily

shut down at least once this week.

Catherine DiMaggio, a mother of four from Long Branch, N.J., who had worked part time in a bakery, said she was still waiting for an unemployment check weeks after filing.

A federal stimulus check covered many of her family's bills last month, but she recently turned to Reformation Community Food Pantry in West Long Branch to help plug this month's gap. It was her first time there.

"The stimulus paid our rent and paid the electric and the cable," Ms. DiMaggio, 40, said. "Now we've got to figure out next month."

No town seems immune to the hardship. In urban centers like

Newark, where the need was already high,

the demand has increased by 50 percent, said Nicole Williams, a spokeswoman for the Community Food Bank.In Jersey City, the state's second-largest city, the governor's March 21

stay-at-home order meant the end of Joseph Ayers's job in a pizza shop. His wife, who worked for the city, was furloughed, and his father-in-law, who lives with the family, also lost his job.

Mr. Ayers applied for food stamps for the first time, but said he was denied because he did not meet the income threshold.

"At one point we were all stable, up until now," he said.

In Summit, about 25 miles west of Manhattan, one food provider,

GRACE, was used to seeing about 100 families for its Tuesday food distribution before the pandemic.

Last week, there were 515 families."The people that we're seeing — their lives have just been decimated," said Amanda Block, the founder of GRACE. "It's not just the usual suspects."

She said the need crescendoed in waves as the economy slowly ground to a halt in an effort to slow the spread of the virus that has

killed at least 6,770 New Jersey residents.

First it was household workers, Ms. Block said, followed by restaurant employees, personal trainers and hair stylists. Now GRACE is seeing more people employed by contractors, after Governor Murphy ordered a stop to most nonessential construction.Still, the need may be greatest in southern New Jersey. An analysis last month by the Brookings Institution think tank found that the economy of Atlantic City could be the

third hardest-hit in the country.

A

recent study by Stockton University estimated that the pandemic's drain on the economy in southern New Jersey could reach $5.1 billion this year.

The extent of the effects on the economy will depend on how soon Jersey Shore businesses

can safely begin to reopen, and how comfortable customers are returning, said Oliver Cooke, a professor of economics at Stockton's William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy.

"The general level of fear is not just going to evaporate overnight," Professor Cooke said.

Manny Agbotse, a 49-year-old father of five, has worked for 13 years as a poker dealer at an Atlantic City casino.

He said he was collecting a 14-day emergency food kit to help replenish his shelves until he is able to get back to work.

"We are low," he said with a nod toward the food. "It's scary."Source: The New York Times

That said, why's this from the Orlando Slantinel? (Oh, I gotta wonder if it's some NYT sign up requirement.)