It is no secret that while social media can be a wonderful world of learning and connection, it can equally be an ignorant cesspool that serves as a window into the darker corners of human nature.

Recently, Canadian clinical psychologist Jordan B. Peterson — author of the international bestseller 12 Rules For Life: An Antidote to Chaos — along with his daughter, decided to bravely pre-empt a foreshadowed character assassination by disclosing on social media that he had sought treatment for clonazepam dependence at a rehabilitation center.

Peterson had been prescribed clonazepam — a type of anti-anxiety medication of the benzodiazepine class — to help manage the stressors associated with the recent devastating news of his wife's cancer diagnosis.

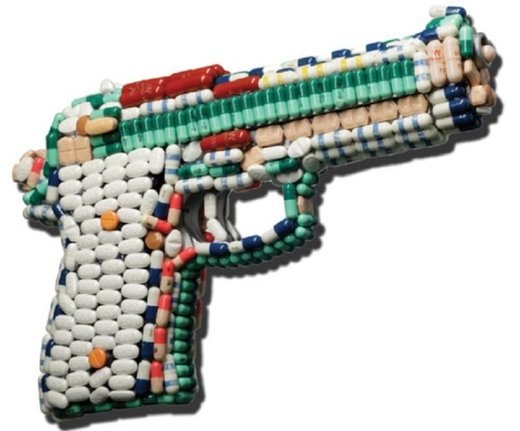

When it comes to the addiction and mental health treatment world, benzodiazepines can be thought of as wolves in sheep's clothing, with the exception of their beneficial use in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. If benzodiazepines are used repeatedly and temporarily to avoid or cope with uncomfortable emotions, thoughts, and memories, their use could lead to the development or worsening of psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety.

They are not first-line treatments for anxiety disorders, and clinical guidelines recommend that their use be restricted to the short term, due to the high potential for both dependency and addiction, as well as other side effects, including severe withdrawal symptoms, sedation, cognitive impairment, and the potential for death.

Full disclosure: I am a clinical psychologist who specializes in addiction, and I bear witness on a regular basis to the literal hell that is benzodiazepine dependence and the effects of addiction-related stigma. Also, Peterson was my undergraduate research supervisor at the University of Toronto approximately 15 years ago, and we have maintained some contact since that time. It is precisely for these reasons that I have decided to shine a light on the stigma directed towards him; it is often in those with whom we have a personal connection that the effects of stigma are particularly salient.

A cursory glance at comment sections or Twitter posts related to Peterson's disclosure quickly reveals beliefs centering on ideas about his moral failing, weakness, and inability to follow his own advice due to seeking treatment.

It might be argued that much of the negative commentary about Peterson is driven by a sense of karmic justice among those who disagree with his positions and politics. Agreed. And it is exactly this kind of moral and emotional reasoning that unearths lazy, sloppy, stigmatizing beliefs.

Look, I get it. Peterson has more than ruffled a few feathers during the past few years. And I own my personal bias as a Peterson supporter, though I steadfastly believe that he has had a net positive effect on the world.

But irrespective of your views on Peterson, it is a gross disservice to everyone to perpetuate harmful myths about people who seek mental health and addiction-related treatment. The fact that the hostility directed towards Peterson has manifested as this type of stigma is a clear indictment against our cultural milieu.

The other tiresome layer to this topic is the need for continued advocacy to dispel the myth that mental health professionals who seek treatment are incapable of imparting clinical wisdom. More generally, health care providers are not gods; they are human, and they go through the same life tragedies that you do. Judging anyone's response to a life tragedy, no matter who they are, and especially without context, is a terribly naïve and self-righteous stance that reflects an ill-formed understanding of human nature.

Peterson is no less susceptible to the ravages of life than the rest of us. Yes, he is equipped with knowledge about how to best respond, which is exactly what he did by seeking treatment. And in doing so, Peterson and his family are embodying the very strength that they have helped to inspire in so many others.

Jonathan N. Stea, Ph.D., R. Psych, is a registered and practicing clinical psychologist in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the University of Calgary. Clinically, he specializes in the assessment and treatment of concurrent addictive and psychiatric disorders. He is interested in topics related to knowledge translation and health misinformation in popular media, especially with respect to addiction and mental health. He has published in Scientific American on topics related to cannabis, opioids, addiction, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

I don't recall him casting stones at folks; he speaks in the abstract about problems best dealt with that way.

Of course, given the thorn of truth he's been in the side of the media/PTB they'll use any ammo they can get. (Akin to attacks on Trump for NOTHING...when Russia shuts down, Dumbocrats come up with more lies to fill the airwaves.

R.C.