To me, however, the two sisters at the heart of the Rochdale scandal are like my surrogate children.

Amber and Ruby [not their real names] are both grown-up now, with children of their own, but I know they still don't feel safe. This week, Amber told me that one of her abusers works in a takeaway close to her home in Rochdale. Her worst fright, though, came last year, when she allowed her daughter to play outside a friend's house with some other children.

Later, after saying goodbye to her friend, Amber turned and found one of her abusers in front of her, staring at her little girl. Smirking, he walked calmly to his car and drove away.

Oh, he knew who Amber was, all right. He was also fully aware that he'd escaped justice — like so many of his mates, who'd also raped or sexually abused the sisters. They, too, still freely walk the streets of Rochdale. So why weren't they prosecuted?

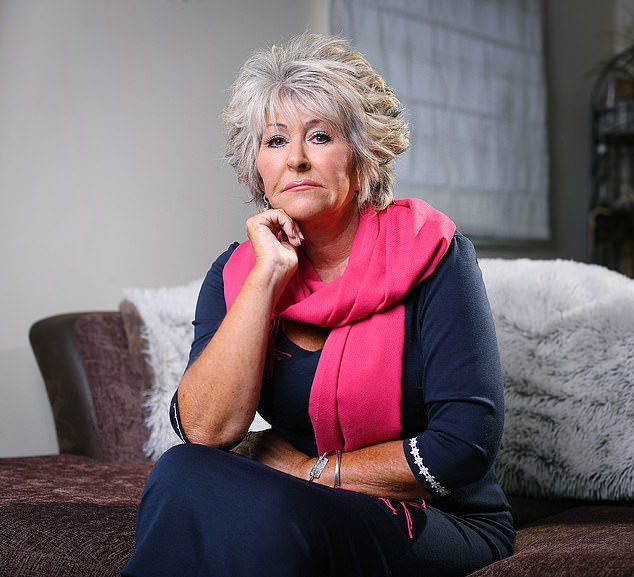

As the former police officer who was once at the centre of the Rochdale sex‑gang investigation — and as the whistleblower who exposed its appalling flaws — I believe I know the answer. It's politics.

Politics appear to drive too many policing decisions. Indeed, my own view is that if you're promoted to superintendent or above, you can freely let go of your conscience, it seems, and move smoothly up the ladder. But judge for yourselves. This is the story of what happened to Amber and Ruby . . . and to the paedophiles who preyed on them and so many others.

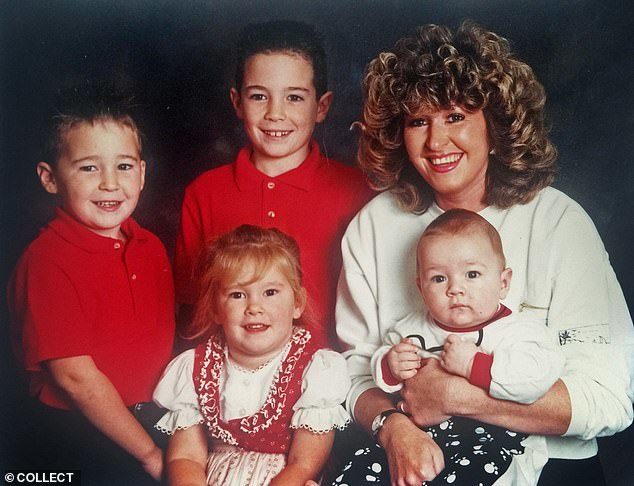

When I graduated from police college in 1997, I was already aged 42 and the mother of four children.

A few years later, I landed my dream job as a family liaison officer with Greater Manchester Police. Then, at the end of 2010, a detective chief superintendent summoned me to his office and asked me to join Operation Span.

It was being set up to investigate the serious sexual abuse of vulnerable white children by men of Asian origin which had been going on for a long time. And he needed me to interview the two sisters at the heart of the investigation.

'If anyone can gain the trust of this family, we know it's you, Mags,' he added. 'But because of their previous dealings with the police, the family is extremely hostile.'

What he went on to tell me almost defied belief.

This was, at least partly, because their child victims had been written off as 'unreliable witnesses' who, according to the Crown Prosecution Service, had made 'lifestyle choices' to become 'prostitutes'.

It got worse.

The police hadn't interviewed Amber as one of the victims. Instead, they'd arrested her — on suspicion of procuring a child into prostitution.

Her crime? Accompanying a friend who was four months younger to the kebab shop where some of the abusers hung out.

Yet at 15, she was an under-age victim herself, groomed by paedophiles and in no sense a 'madam'.

Rochdale police never charged Amber. By arresting her, however, they managed to traumatise and alienate her entire family.

Meanwhile, her sister, Ruby, had been raped by a married Asian man at the age of 12, and subsequently had an abortion. Unbeknown to her, the police had taken the foetus, which was currently stored in an 'exhibits' freezer.

My stomach lurched. Surely that was illegal?

Yet now, not only was I expected to break the news about the foetus to Ruby, but I was somehow supposed to win over two sisters who'd been badly let down by the police.

That didn't worry me, though. What did — very much so — was the thought of gaining the trust of vulnerable girls, only for the police to let them down yet again.

I knew only too well that this could happen, and not just because of their previous experience. As a police officer, I'd already taken part in a similar investigation in 2004 — and all the men had escaped scot-free.

'Thanks, but no thanks,' I told the chief superintendent, standing up abruptly as he looked at me in astonishment.

Five years before, I'd had high hopes when I joined Operation Augusta, which focused on girls sexually abused by Asian gangs in Manchester.

Early on, I'd been astonished to discover that social workers had compiled lists of dozens of these abused children, and repeatedly called in the police — but nothing had been done.

Yet now, the police seemed to have had a change of heart and had become fully committed to bringing the abusers to justice.

The fact that they were predominately of Pakistani origin barely registered: I've never been remotely racist.

The evidence was shocking. White girls — as young as 11 and all in care homes — had initially been approached by Pakistanis in their teens and 20s, who then became their 'boyfriends'.

After coercing them into sex, their abusers would pass them on to older men for sex, using cash incentives or threats of violence, or both.

There were sex parties involving up to 20 Asian men and one white girl, who was expected to have sex with them all in return for a few quid.

One day, I drove with a victim around the area where the men operated. On spotting a man emerging from a black 4 x 4, she suddenly covered her face with her hands. 'He's one of 'em who's been abusing us. I'd recognise him anywhere,' she said.

Later, back at the station, I did a check on the vehicle. Within minutes, I had a phone call from an officer who specialised in police corruption. Why had I just run that registration check, he asked.

After I'd explained, he told me: 'Right, well, we have this person under surveillance. He's a serving [police] officer, so let us deal with him, OK?'

So, it wasn't just takeaway workers and taxi drivers involved. If this was an organised ring of abusers, its tentacles appeared to have spread even into the police force.

By spring 2004, we had an initial list of almost 207 Asian men who we believed had been abusing at least 26 children. And we knew this was the tip of the iceberg.

Unfortunately, two years into Operation Augusta, I had to take several months off work. My husband Norman was in the final stages of colon cancer, so I dropped everything to care for him.

Still, I left Augusta with an easy conscience, utterly convinced that dozens of the paedophiles we'd identified were about to be charged.

Norman died on July 5, 2005, leaving me shocked and numbed. When I finally returned to work that September, I asked for an update.

'Oh, yeah, they've warned a couple of the younger lads under the Child Abduction Act,' a colleague told me.

No one had been charged, let alone convicted. I was devastated. All that work, and for what? It just didn't make sense.

I tried to speak to my bosses about it, but hit a brick wall.

In hindsight, perhaps I should have looked more closely at current events. On July 7, 2005, four home-grown terrorists had exploded bombs in London, killing 52 people and injuring almost 800. The last entry on the Augusta database had been made on July 6 — and the operation had been shut down the following month.

To the police, I believe, revealing the extent of child grooming of white girls by Muslim men would have been akin to adding petrol to an already inflammatory situation

By shutting down the operation, the police could avoid accusations of Islamophobia and the threat of riots on the streets.

Nothing else makes sense to me. To my mind, it was more convenient for the government to ignore the plight of a few girls from the so-called 'underclass' than to tackle the crimes of their abusers.

So now, five years on, I was being asked to take part in a similar exercise, with no guarantee it wouldn't end the same way.

But as I got up to leave, the chief superintendent told me to sit back down again.

'There'll be no repeat of Operation Augusta,' he insisted. 'I give you my word that will not happen this time. I know it's a massive challenge, but we need these girls as witnesses, Maggie. They're our best chance of putting these men away.'

He also reassured me that both the police and Crown Prosecution Service had decided that, far from being a procuress, Amber was purely a victim. I accepted the job. My first task, I decided, was to try to befriend the girls' mother, Lorna [also not her real name].

From the information we already had, I learned that she'd repeatedly told the authorities — police, social services, sexual health, council and education representatives — that her girls were being sexually abused. Nothing had been done, despite the fact that one of her daughters was 12.

It took weeks of phone calls, just chit-chat, to reach the point where Lorna agreed to meet for a cup of tea in a nearby supermarket. That day, I told her about my own children and we connected properly for the first time.

It was obvious to me that Lorna loved her kids — all seven of them. But she was just exhausted, trying to juggle so many balls in the air. In many ways, I admired the fact she was still standing.

Talking to me soon became a form of respite, even if I was a copper. One day, as we walked around a local reservoir, she suddenly confided: 'Those men, they pulled out a gun and threatened to kill Amber, you know.'

Everything was falling into place. We had DNA proof. We had detailed statements. So why was it that when I delivered the spectacular news to my bosses, I sensed something wasn't right . . .

It was the first time she'd touched on the abuse of her girls.

She sighed. 'I kept banging on doors, but no one would listen. Then, just when I thought it couldn't get any worse, they arrested Amber.

'They put her in a police cell for seven hours. She was 15 and terrified out of her wits. She'd done nothing wrong, Maggie.

'It left her scarred, up here,' Lorna said, tapping a finger against her head. 'She's scared stiff because she thinks they're gonna throw her in a cell again and never let her out.'

I assured her that, this time, everything would be different: 'My bosses have given their word. We'll support you all right through this process. Trust me.'

At this point, Ruby, now 15, still lived at home. She had anger issues, a Statement of Educational Needs and went to a special school.

Amber, now 18, had eventually broken away from the grooming gang, found a boyfriend and had a child. After the relationship foundered, she was forced to live in a tiny bedsit on the top floor of a hostel for the homeless — hardly the ideal place for a three- month-old baby.

Soon afterwards, Lorna took me to meet Amber. The girl who unlatched the door looked like a frightened child, but at least her baby boy seemed clean and happy.

She was horribly isolated. Simply because she'd been arrested in connection with an alleged sexual offence, social services had banned her from a drop-in centre for young mothers and even from taking a college course.

In my opinion, this was outrageous and cruel. I firmly believe that there's no such thing as a good victim or a bad victim, particularly when we're talking about a child who was raped on a daily basis. On top of that, Amber was frightened to leave the bedsit in case she bumped into the men who had abused her. So day after day, she sat alone, nursing her son in a shelter for the homeless.

That day, I rocked her baby to sleep. Afterwards, I started seeing Amber most days, trying to offer support and encouragement. Eventually, she agreed to let me interview her.

She'd had sex with one of her abusers, she said, after he'd got her drunk on Jack Daniel's. After that, they'd often gone to a place called The Balti House, where she'd been introduced to other men.

At first it was fun: along with other girls, she'd eat, drink and watch videos.

But all too soon Amber was being plied with alcohol until she was drunk — then ordered to have sex with men she knew only by their 'street names': Billy, Daddy, Car Zero, Cassie Cars, Tiger, Taz, Tariq, Pino, Saj ... the list went on and on.

Over subsequent interviews, Amber named 33 suspects, many of whom picked up young girls in their cars and raped them on the moors, far from view.

She also described the moment a man pulled a gun on her and Ruby because they'd refused to have sex with him: 'That made him mad, so he told me he'd kill me, shoot me. I was really scared.'

During another interview, she confided: 'Ruby sees these men as her friends. She doesn't want to help the police because she doesn't want her friends to go to prison.'

Yet I knew that Operation Span was particularly keen to place Ruby's account on the record, because DNA evidence would tie her aborted foetus both to herself and her abuser.

Meanwhile, the case was building strongly. We had evidence of dozens of abusers, and were confident that the network would be smashed.

Ruby refused to cooperate at first, but that April I had a break-through. 'People have let you down,' I told her. 'I'd like to speak to you so that they don't put other children through what you've been through.' She sighed, and suddenly agreed to talk.

'There's a man who picked me up from school,' she said. 'I'd have sex with him. He took me to another house, where there were ten men sat in a circle. They passed me around like a ball and took it in turns to have sex with me.'

There was a lot of boasting from the abusers about 'chilling with white girls'. Indeed, looking back, I believe strongly that we should have brought in a 'racially aggravated' element to the investigation. There was no doubt these girls were being targeted for their ethnicity — and the perception that white girls are 'easy'.

My heart ached for Ruby as she named the men and identified where they'd taken her. At one address, they kept a list of 20 names on the back of the door. Each man would tick a box to say he'd had sex, and then leave cash in a paedophile 'honesty' box for use of the premises.

Only one white girl was abused at a time, no doubt because a lone child is more vulnerable and easier to control. There are also no witnesses should she one day decide to cry rape.

At 12, Ruby was drinking neat vodka from a bottle, and often being sick in the cars that took her to other northern towns to have sex with strangers.

And then, of course, she became pregnant. When I told her the police still had her foetus, she looked at me in horror. 'What! That's not right. How could they do that? It's terrible.'

I explained that we needed a sample of her DNA so we could prove who the father was. She whisked the consent form from me: 'Just show me where to sign.'

After six months, everything was falling into place. We had DNA proof. We had detailed statements. Amber had identified eight abusers in her very first video identity parade and would soon be picking out the rest.

So why was it, then, that when I delivered all this spectacular news to my bosses, I sensed something wasn't right?

They should have been ecstatic. Instead, it felt like someone had died.

As I pondered over this, a senior officer turned to me. 'Maggie, let's be honest about this. What are these kids ever going to contribute to society?' he said. 'In my opinion, they should have just been drowned at birth.'

For once in my life, I was rendered utterly speechless. What was going on?

As I'll be revealing tomorrow, I was soon to find out . . .

Comment: Maggie Oliver reveals how the authorities attempted to avoid prosecuting Asian paedophiles in the last part of the series here. Apparently nothing has changed in Rochdale - she believe the gangs are still operating: