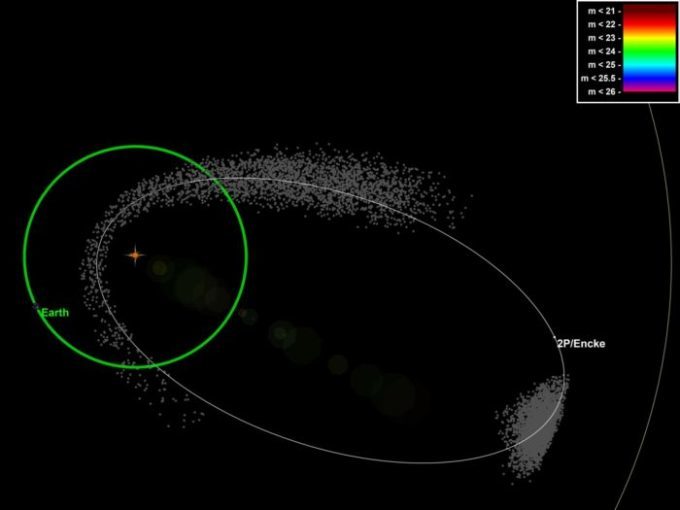

Starting on June 5 and running until July 18 of each year, Earth passes through a stream of meteoroids in space - bits of rock and ice left behind by a comet known as 2P/Encke as it travels around the Sun. As these bits of comet debris are swept up by the planet's atmosphere, they produce bright flashes of light across the sky. This is the Beta Taurid meteor shower, which reaches peak activity on June 28-29.

While Comet Encke is also responsible for the Southern and Northern Taurid meteor showers, which send streaks of light across the night skies in October and November, respectively, there's a catch to the June Beta Taurids.

Hardly anyone has seen a Beta Taurid meteor. Unlike most meteor showers, this one occurs during the day, because the meteoroids in this part of the stream are coming at Earth from the direction of the Sun.

A possible exception to this, however, is a very notable one - an explosive fireball meteor that quite dramatically lit up the morning sky over central Russia, on June 30, 1908. This explosion was so powerful that it flattened around 80 million trees across more than 2,000 square kilometres of the local terrain. It is now known as the Tunguska Event.

Fortunately, such an event was only expected to happen once every 1,000 years, or so we once thought.

Where Did The Tunguska Impactor Come From?

In his research of the Tunguska impact, Peter Brown, a professor of physics and astronomy at Western University in London, ON, traced back the trajectory of the object, based on the pattern of the flattened trees. He discovered that it closely matched with the trajectory of the Taurid meteoroid stream.

According to their paper, several large asteroids have already been discovered that have similar orbits to Comet Encke, and two large fireballs reported during the 2015 Southern Taurids meteor shower, in October, already provide evidence that the Taurid stream contains some larger objects.

If the Taurid swarm exists, it could be the source of the asteroid or comet fragment that caused the Tunguska Event, and it could contain many more similarly-sized objects.

If that is the case, these objects could - potentially - impact Earth far more often than once every 1,000 years.

"There is strong meteoric and near-Earth object evidence supporting the Taurid swarm and its potential existential risks," Clark said according to Western News. "But this summer brings a unique opportunity to observe and quantify these objects."

According to their research, the Taurid swarm may be making a relatively close pass by Earth towards the end of June 2019. Based on the known shape of Comet Encke's orbit, the swarm would fly 'underneath' the planet at a distance of about 30 million kilometres. While that is far enough away for there to be no worries of an impact now, it is close enough to use telescopes to search for the swarm.

Comment: There is plenty of reason to worry. Meteors sightings have been increasing in number all over the world. It's just a matter of time before we have another Chelyabinsk event.

"In the next month or so, we're going to be making the closest pass to the centre of this Taurid swarm - the closest we've made since 1975," Brown told the CBC.

"So for the first time with modern instruments, we can actually test the hypothesis that there's all this very dense material, home to tens [of metres] to hundreds of metres-sized objects, by actually looking ... at that centre."

Since the objects in the swarm would be travelling past us from the direction of the Sun at that time, they would be showing their dark sides to us, and they would be lost in the glare of daylight. Therefore, the team is waiting until August, since they believe the swarm will have passed us by then, and thus the objects in the swarm would be visible at night. They plan to use the Canada-France-Hawaii telescope, atop Mauna Kea, to view them at that time.

Is There A Danger

According to NASA, there are no known asteroid or comet impact threats for at least the next 100 years. That assessment, of course, only accounts for known asteroids and comets.

Comment: You can read more about that here: Meteorites, Asteroids, and Comets: Damages, Disasters, Injuries, Deaths, and Very Close Calls

If the Taurid swarm is proven to exist by the Western team's observations, and they do find that it contains large objects, measuring tens to hundreds of metres wide, this could, potentially, pose a threat to us.

While this is the closest pass of the swarm since 1975, according to their simulations, the researchers told CBC News that there are two upcoming passes, in 2032 and 2036, that will be even closer.

It would benefit us to know if this swarm of meteoroids actually exists, and if there are dangerous objects within it, so that we have time to prepare before the swarm returns for those close passes.

"It keeps reminding us these things can happen, and let's be honest, they will happen," Clark told Western News. "We don't know if it will be in a thousand years, a hundred years, or tomorrow. It reminds people of how small and exposed we are in the cosmos."

Sources: Western News, CBC

Comment: See also: