The archaeologists cannot bless roadwork enough. Especially in Jordan. It's just that certain thrusts of the mechanical shovel, such as the one in late 2016 at the school entrance in the village of Bayt Ras, in the north of the country, have a knack for unearthing secrets from the depths of the past. In the present case, it is a Roman tomb that was dug into the side of a hill, and whose existence was just revealed by the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, after securing access to the site.

"This tomb, which consists of two funerary chambers and contains a very large basalt sarcophagus, is in an excellent state of conservation, even though it appears to have already been 'visited.' It is part of a necropolis located to the east of an imposing theater that was recently unearthed," says with enthusiasm Julien Aliquot, one of the three researchers from the research unit Histoire et sources des mondes antiques (HiSoMA),1 which had investigated this hypogeum in the spring of 2017 and 2018, as part of two on-site surveys. "The tomb is located on the site of the ancient city of Capitolias, which was founded in the late first century CE, and was part of the Decapolis, a region that brought together Hellenized cities (provided with Greek-style institutions but belonging to the Roman Empire) in the southeastern area of the Near East, between Damascus and Amman."

An animated timeline

Many things are remarkable about this subterranean tomb of 52 m2. Let's start with the impressive number of figures (nearly 260, including gods, humans, and animals) painted on the walls of the largest chamber. Of course other Roman tombs from the Decapolis also offer sumptuous mythological decor, but none of them can hold a candle to this one in terms of iconography. "These teeming figures compose a narrative that is arranged on either side of a central painting, which represents a sacrifice offered by an officiant to the tutelary deities of Capitolias and Caesarea Maritima, the provincial capital of Judaea," says Aliquot.

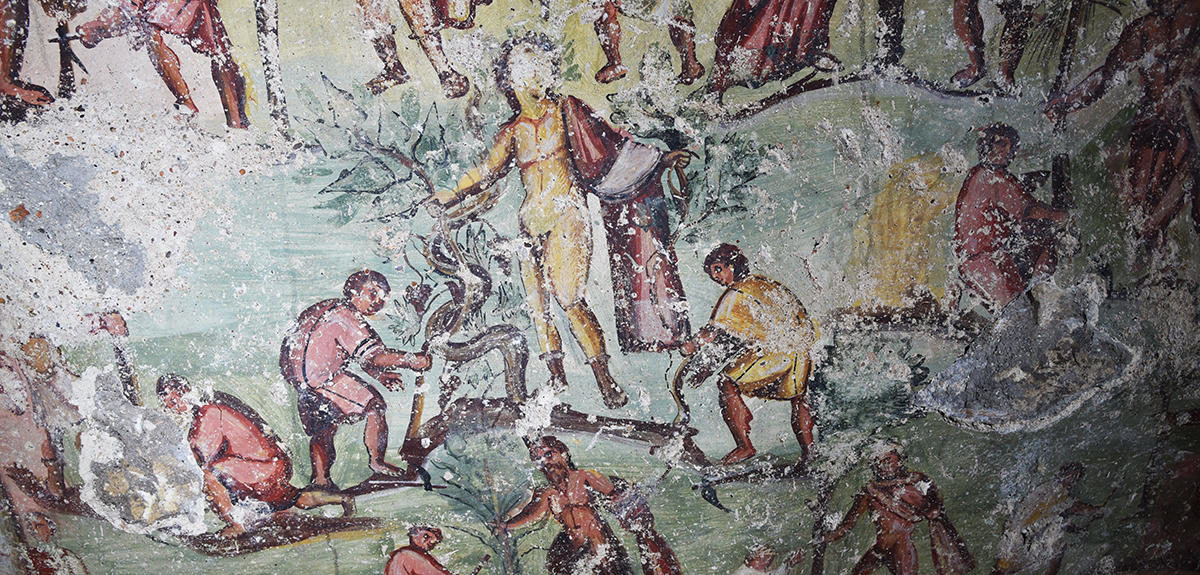

Whoever entered the tomb, before it was closed, first glimpsed on his left banqueting deities lying on beds, and tasting offerings brought by humans smaller than themselves. Again to the left of the entrance, a second painting with a country landscape shows peasants busy working the earth with the help of oxen, gathering fruit, tending grapevines... The next panel depicts woodcutters chopping down various species of trees with the help of gods, an exceedingly rare subject in Greco-Roman imagery.

No less original, to the right of the entrance, is a large painting illustrating the building of a rampart. "Characters resembling architects or foremen stand alongside laborers who are transporting materials on the backs of camels or donkeys, with stone cutters or masons climbing walls, sometimes resulting in accidents. This precise and picturesque scene of a construction site is followed by the last painting, in which a priest offers another sacrifice in honor of the city's guardian deities," explains Aliquot. Finally, displayed on the ceiling and walls on both sides of the entrance is a more classical composition evoking the Nile and the marine world, in which nymphs ride aquatic animals flanked by cupids, while a central medallion combines signs from the zodiac and the planets around a quadriga.

First Aramaic Comics? Already unique on account of the abundance and originality of its iconography, this tomb is even more so through the inscriptions that accompany the scenes depicting the construction site. "These 60 or so texts painted in black, some of which we have already deciphered, have the distinctive feature of being written in the local language of Aramaic, while using Greek letters," says Jean-Baptiste Yon, of the same research unit. "This combination of the two primary idioms of the ancient Near East is extremely rare, and will help to better identify the structure and evolution of Aramaic. The inscriptions are actually similar to speech bubbles in comic books, because they describe the activities of the characters, who offer explanations of what they are doing ('I am cutting (stone),' 'Alas for me! I am dead!'), which is also extraordinary."

The birth of Capitolias

With regard to the meaning of this very rich iconographic and textual arrangement, researchers are inclined to see it as an illustration of the various stages involved in the founding of Capitolias: consultation of the gods on the choice of site during a banquet, clearing of the plot, raising of a wall, thanks offered to the gods after the construction of the city... "According to our interpretation, there is a very good chance that the figure buried in the tomb is the person who had himself represented while officiating in the sacrifice scene from the central painting, and who consequently was the founder of the city," comments Pierre-Louis Gatier, of the same research unit. "His name has not yet been identified, although it could be engraved on the lintel of the door, which has not yet been cleared."

An international consortium of experts was created by the Department of Antiquities of Jordan for the study, conservation, and development of this one-of-a-kind jewel. Under the supervision of the Sustainable Cultural Heritage Through Engagement of Local Communities Project,2 hosted at Amman by the American Center of Oriental Research, the new Bayt Ras tomb is, among others, mobilizing Claude Vibert-Guigue, a specialist on ancient painting at the research unit Archéologie et philologie d'Orient et d'Occident,3 and Soizik Bechetoille, an architect at the French Institute for the Near East (Ifpo),4 in addition to the historians and epigraphists from HiSoMA, as well as two Italian institutes, the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione ed il Restauro (ISCR) and the Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA). The results of this ongoing research will be presented in Florence in January 2019, during the 14th International Conference on the History and Archaeology of Jordan.

Watch a short film on this discovery

Footnotes

Reader Comments