Byron Ruttan never had much luck with fathers or father figures.

His own father left town when he was three. His mother took up with a new man, but he would commit an armed robbery and land in Joyceville Institution, a federal prison just outside Kingston.

Byron never had much luck with courts, either. It was a court that assigned him a mentor - another paternal figure - when he was 12 years old, in 1979.

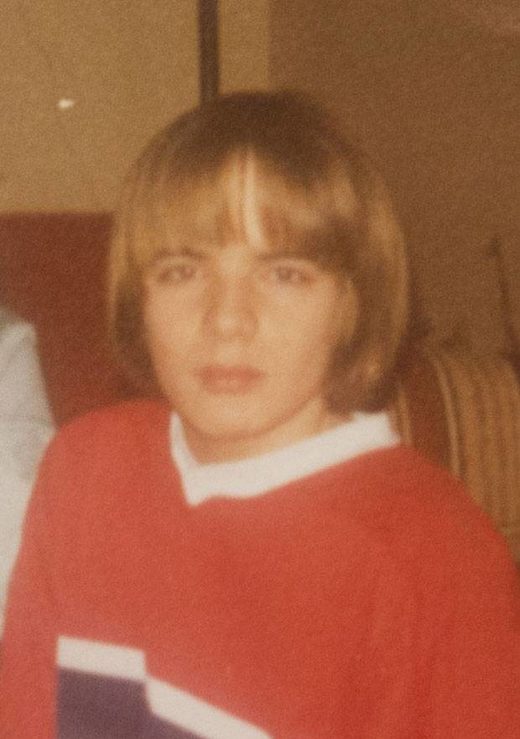

He had been cutting class. Living with his mother and three sisters in a rented townhouse in Kingston's tough north end, where all the families he knew lived on mothers' allowance or welfare, he would spend school days hiding out in a quarry. Sometimes he would steal $5 from his mother's purse. Eventually, the authorities brought him into court. (Whether it was police or child-protection workers is not clear, after all these years.) He was a handsome boy, blond, with strong cheekbones.

The judge told him that his mother couldn't take care of him on her own. Through a juvenile-diversion program meant to help young people in trouble stay out of criminal court or state care, a young man would become a kind of big brother to him. Byron had no choice in the matter: The judge issued a court order requiring him to accept the mentor.

Being assigned Mr. Williamson as a mentor was only the beginning of Byron's bad luck with the justice system. In 2009, police pressed charges against Mr. Williamson. But although a Kingston jury found him guilty of all charges, the Supreme Court of Canada ultimately let Mr. Williamson walk free - a decision that had nothing to do with his guilt or innocence. Rather, the country's highest court ruled that the 35 months it had taken to determine his guilt amounted to "unreasonable delay."

It was a pivotal moment - the sort that arrives every generation or so - when the justice system takes stock of itself.

That self-examination hinged on the case of yet another convicted criminal. B.C. resident Barrett Jordan had asked the Supreme Court to throw out his conviction for drug dealing on the grounds that his own trial, which took four years to complete, demonstrated the disappearance of "timely justice" from Canadian criminal courts.

The Supreme Court agreed.

The court's ruling in the Jordan case, on July 7, 2016, would strike the legal system like an earthquake - by mid-November, murder charges would be thrown out in two provinces over delay; by spring, federal and provincial justice ministers would meet in emergency session to figure out how to speed up the system. But Byron Ruttan was collateral damage of an even more immediate kind. Now 50, he was the first crime victim whose case was tossed overboard as a result of Jordan - on the very day the Supreme Court released the B.C. drug dealer from responsibility for his crime. In legal terms, R. v. Williamson was the "companion case" to R. v. Jordan. Jordan was the court's template for crushing delay. Simultaneously, the court applied the new template in Williamson.

Mr. Ruttan's story has never been told, mostly because of a publication ban on his identity, a restriction common in sexual-assault cases. But after being approached by The Globe and Mail last winter, he chose to ask a judge to lift the ban, and on Aug. 11, the judge did so. Having stayed silent through severe childhood sexual abuse, Mr. Ruttan was now ready to speak of his life, and the justice system, and how the ruling in R. v. Jordan affected him in ways large and small.

"I can't say I didn't think about it every day, because I did," he says of the abuse. For years he tried to chase it from his mind. "I thought, 'Leave it buried and eventually it will go away.' But it didn't."

Byron Ruttan was raped at least 50 times when he was 12 and forced to perform oral sex on about 10 occasions, according to factual findings made by the trial judge at the sentencing of Mr. Williamson. But he was ultimately denied the justice he sought, as the system suddenly switched the rules on delay. Bad timing was Mr. Ruttan's faithless yet inseparable escort throughout the course of the legal proceedings.

He was, as always, out of luck.

It is a sunny, cold February day in Verona, a town of 1,800 people nestled between two small lakes, 20 minutes' drive north of Kingston. Mr. Ruttan lives in a small rented house on the main street, with his common-law wife of 15 years, with whom he has two children.

The fatherless boy has been a father now for three decades. He has four children in all. A fifth, Brandon, had cystic fibrosis and died in 2008 at 25; a framed photo of him at the age of 5 sits on a wall unit in the living room. The children are 10, 18, 28 and 30. Three live in the house; the fourth has grown up and moved on to a nearby town. Around 1993, Mr. Ruttan went to Family Court and obtained custody of his first three children after his relationship with his previous spouse ended.

A tiny space heater provides the only warmth on the main floor of the cramped but homey house, its walls covered in framed pictures of the children. The temperature outside today is hovering around zero. Inside, the front room is cold, and Mr. Ruttan wears an overcoat.

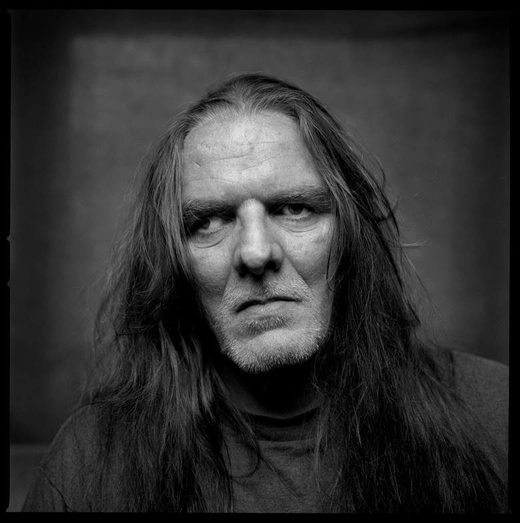

He is a hulking figure, well over six feet and 200 pounds. His hair, which he has not cut in a decade, is held in a long ponytail. He looks older than his years. He has had a lazy right eye from birth. (It was corrected by glasses when he was younger, and could be corrected again, by surgery, but he hasn't got around to it. The handsome 12-year-old is no more. His face reads like a victim-impact statement.

"Rugged, rough around the edges," is how Mr. Ruttan's eldest son, Bryon, describes him. He says that when he refers to his father as "the one-eyed, long-haired guy," everyone in town knows whom he's talking about.

Mr. Ruttan has lived many years with anger. "Certain things would set me off really bad. I could fly off the handle really easy," he says. He shuts his pet Rottweiler, Butch, into the bathroom while a reporter is visiting; the dog cries. Butch is notorious in the family for having once been chased by a Jack Russell terrier.

Mr. Ruttan is on medication for depression and other psychological problems. He has been to jail "eight or nine" times - for assault, fraud, theft. Sometimes just doing weekends, sometimes in full-time lockup, the longest stretch being three months, and the total time behind bars about a year. But not since he joined up with his spouse in 2000.

Supporting a family has never been easy for him. At times, he did not pay his rent, and life became a series of hurried midnight moves. "I wasn't much for budgeting," he says. "I made sure they had food. That was the most important thing. I made sure that there was love there." At the moment, he receives Ontario disability payments.

Over the years, he told his spouse, and all of his children, about Gavin (the name his former mentor calls himself) Williamson. But like many victims, Mr. Ruttan never went to the police, for reasons he would give voice to at the trial.

Then one day in the fall of 2008, he told his probation officer, Sue Corcoran, that he had to leave their monthly meeting early to see his pharmacist. She asked what meds he was on. When he gave her the list, she wanted to know why there were so many.

He told her what had happened. He was 41.

"It felt good, really good," he recalls thinking. "I got a lot off my chest."

She phoned the police. Three months later, on Jan. 6, 2009, in plain clothes, Detective Constable Jason Cahill of the Kingston police sexual-assault unit, accompanied by Detective Nancy McDonald, each of them with a gun under their suit jackets, went to Gananoque Secondary School and arrested Mr. Williamson in the principal's office, to which he had been summoned near the end of the day.

It was a quiet arrest. Det. Constable Cahill told Mr. Williamson, a teacher of history and geography, that he would be charged with "historical sexual offences," and advised him of his rights. Mr. Williamson said he did not want to speak to a lawyer. Det. Constable Cahill decided it was not necessary to place him in handcuffs. The two officers drove Mr. Williamson in an unmarked car to the police station, where another officer again advised him of his right to counsel.

Det. Constable Cahill had been on the unit only a few months, but he did an expert job of breaking through Mr. Williamson's initial denials. He gave the teacher a way to excuse his conduct by suggesting that Mr. Ruttan had been the aggressor, and that in such circumstances what was legally wrong may not have been morally wrong. Then he threatened to phone Mr. Williamson's parents; the teacher's father was terminally ill (he would, in fact, die less than a year later). Without a lawyer, hesitantly, gradually, Mr. Williamson admitted to engaging in some sexual activity, including a kind of simulated anal sex, with young Byron. The interview was recorded in a two-hour video.

"He called me," Mr. Ruttan said of Det. Constable Cahill, "and said, 'You won't believe it, he wouldn't shut his mouth about it.'" (Det. Constable Cahill did not respond to requests for comment for this story.)

The prosecution had a strong foundation on which to build a case. Mr. Williamson had confessed to breaching the line that adults, particularly those in a trust situation, must not cross with children.

Six days after the arrest, a judge granted Mr. Williamson bail.

Three teenage sisters and their stepmother were found in a submerged car in a canal in Kingston in June, 2009. What did this have to do with the Williamson case? Nothing, and everything. The young women's father, mother and brother were charged with their murders. Three accused, four counts each, the Crown calling it an "honour killing." The Shafia family case was long, and complicated. And it was slowing down the queue in the Kingston court system.

If that had been the only thing holding up the trial of Mr. Williamson, the Shafia trial might not have mattered.

But three days before the Williamson preliminary inquiry was to begin, in November, 2010, nearly a year after the schoolteacher had been charged, a bureaucratic error occurred: The court advised the prosecutor's office that the judge in the case had a funeral to attend that afternoon. The prosecutor let the witnesses know not to attend. No one told Mr. Williamson's defence counsel, Sean May of Ottawa. When the day came, Mr. Williamson and his counsel showed up in the courtroom. So, too, did the judge. No one has ever explained the erroneous advisory about the funeral.

The case was put over until Feb. 22, a three-month delay to schedule a one-day hearing.

When that day arrived, Mr. Williamson and his counsel again showed up at the courthouse, only to be told by court officials that neither the judge assigned to the case nor the investigating officer, Det. Constable Cahill, were available. In fact, the judge was at court and was available - and so, the hearing could, in fact, have begun. No one has explained that error, either.

But the result was all too real: another three-month wait, until May. The Shafia murder case was clogging up valuable court time. More bad timing for Mr. Ruttan.

Finally, the preliminary hearing took place, at which the judge ruled that there was enough evidence to go to trial. A date could be set. Mr. Williamson had asked for a jury trial, as was his right; but there was a shortage of places in which to conduct it. Once again, the Shafia murder case was an issue; having made it through a preliminary hearing, it was now occupying one of the two courtrooms used for jury trials at the Frontenac County Courthouse in Kingston. More than three months were scheduled for that complex case, causing several other jury trials to back up.

At last, the trial of Gavin Williamson was set for December, 2011 - 17 months after the preliminary hearing, and 35 months after his arrest.

But with his day in court looming, Mr. Williamson sought to have the case thrown out - for delay. His lawyer, Mr. May, brought what is known as an 11(b) challenge. Section 11(b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees that anyone charged with an offence has the "right to be tried within a reasonable time."

Before the Jordan ruling, reasonable-delay cases were based on flexible guidelines: Judges weighed the seriousness of an offence against the length of the delay and the harm (known as "prejudice") that such a delay would cause to the accused.

Mr. Williamson contended that he had experienced great prejudice: He told the court that he felt as if he had been under "house arrest" for two and a half years. What's more, he added, his relationship with a nephew had been affected by a bail condition that he not be alone with a child under 16. Ontario Superior Court Justice Gary Tranmer, a former personal-injury lawyer, didn't buy it. The house arrest was self-imposed, he said - and besides, there was no actual prejudice (such as witnesses' memories fading over time, making it harder to mount a defence). He also found very little "inferred prejudice" (such as the emotional pain of waiting for trial).

In the end, Justice Tranmer rejected the challenge, ruling that the delay, while well beyond the norm, was not extreme and was outweighed by the seriousness of the alleged offence. "Society's interest in protecting vulnerable children," he wrote, "is very high."

Two months later, the trial began.

Mr. Ruttan was the Crown's first witness. Under methodical questioning from Crown counsel Megan Williams, he described the first instance of rape, in a single bed in Mr. Williamson's university dorm room. He used simple terms and few words. He said it had hurt.

"Are you able to describe anything about the pain that you recall?" Ms. Williams asked, according to the court transcript.

"It's a pain that I don't think you can describe," he said.

And why hadn't he spoken up?

"Back then it was the wrong thing to have happen to you," he replied, adding that his classmates would think "that I was gay or something like that" and that he doubted he would be believed.

And how, asked Ms. Williams, had the abuse affected his life? He replied that he had missed out on a lot, and she asked what.

"Just being a normal kid," he told the courtroom.

Justice Tranmer later described Mr. Ruttan's testimony as calm and straightforward, given "as if with a flat affect." The witness, he said, did not embellish. He did not lament his lot in life, and he described his feelings only when asked directly about them.

Mr. May's cross-examination was tough. He had obtained, through a pretrial process, a decade's worth of deeply personal medical files from Mr. Ruttan's psychiatrist. Mr. Williamson had the judge's permission to view those records in the presence of Mr. May or another lawyer from his office.

From these medical files, Mr. May drew out intimate details, asking Mr. Ruttan about his psychological problems.

He moved on to Mr. Ruttan's criminal record: Assaulting a man he felt had bullied his eldest son, in a case heard just seven months earlier. Defrauding a store when he was 29 by renting stereo equipment, then faking a break-in and calling police to make a false report, and pawning the equipment. Stealing cash from an employer for whom he made food deliveries when he was 21.

"Lying, deceit, making things up, is a pattern in your life, to be fair to you?"

"It was, yes," replied Mr. Ruttan.

And then his childhood silence came under attack. Not only had Mr. Ruttan not cried out in that dorm room all those years ago, Mr. May observed, but he had "gone back and back and back" to be with Mr. Williamson. And even though other students on the all-male floor had become Byron's friends, buying him a bike with refund money from their empty beer bottles, he never told them, or anyone else about what he had now testified Mr. Williamson had done to him.

"You never breathe a word."

"No."

"It doesn't make much sense."

"No, it doesn't."

Mr. May remained on the offensive: "You are unhappy with a lot of the problems that you have had in your life, and you have found someone to blame, and you have manufactured and fabricated accusations against him? That's what I'm suggesting to you, sir."

"You can suggest it all you want," Mr. Ruttan replied, "but I know the truth."

The next day, Mr. Williamson testified in his own defence. He flatly denied any sexual activity had happened. He had been in shock when interviewed by Det. Constable Cahill, he said, fabricating incidents out of a "survival instinct to protect my parents mostly." He said that the law should require corroboration for Mr. Ruttan's allegations. (Parliament ended a requirement for corroboration of a sexual-assault complainant's testimony in 1983.) He accused Det. Constable Cahill of stereotyping him as a single, male teacher. "I did not assume," he said, "I would be treated like this in this country in 2011."

The jury convicted Mr. Williamson on all charges. At sentencing, Justice Tranmer cited two tough-on-pedophile rulings from the Ontario Court of Appeal - both written by Justice Michael Moldaver (who by this time was on the Supreme Court, where he would soon play a role in the Williamson case far beyond these citations). "Adult sexual predators who would put the lives of innocent children at risk to satisfy their deviant sexual needs," Justice Moldaver had written, "must know that they will pay a heavy price."

The Crown asked for a prison sentence of six to nine years. The defence asked for house arrest.

In sentencing Mr. Williamson, Justice Tranmer took note of Mr. Ruttan's victim-impact statement. "He grew up in life scared, angry, lost and very depressed. He lives with shame and hate every day and has nightmares at night, waking up in cold sweats and then staying awake the rest of the night. He is on medication which causes mood swings. He doesn't like to talk to people or be around people."

As mitigating factors, he cited Mr. Williamson's clean record and lack of threats against Mr. Ruttan.

He sentenced Mr. Williamson to four years in prison. Mr. Williamson filed an appeal, and was released on bail once again.

"He was out," Mr. Ruttan says, "before he was in."

R v. Williamson: Read the key rulings'A very difficult case'

2011: Ontario ruling on trial delay

2014: Ontario appeal ruling

2016: Supreme Court's Williamson ruling

2016: Supreme Court's R v Jordan ruling

The right to be tried in a reasonable time turns on the meaning of the word "reasonable." That, in turn, depends on context. And so, while, 4,300 kilometres away, the Jordan case was making its way through B.C.'s courts, the Ontario Court of Appeal set itself the task of separating the reasonable from the unreasonable in the delays that had beset the case of Kenneth Gavin Williamson (which the court calculated as taking 33 months, after deducting two months for delay caused by the defence.)

Mr. Williamson had suffered no obvious, direct harm from those delays, the three appeal-court judges said. He had not been in jail while awaiting trial; his bail conditions weren't onerous; and he had been receiving full pay while under suspension by the school board.

On the other hand, the justices noted that a long delay was, by definition, harmful. "The inferred prejudice is significant," the unanimous court wrote in August, 2014, pointing to "the stigma of being under a public cloud." That a jury had found Mr. Williamson guilty was not deemed relevant at this stage of the reasoning; to the court, what mattered was that he was presumed innocent during the period of delay.

Mr. Williamson had committed an "especially despicable" crime, they wrote; still, neither the Crown nor the Superior Court had taken his 11(b) rights seriously - Mr. Williamson had been turned away from the two preliminary hearing dates because of scheduling errors. By contrast, the defence was diligent in trying to move the case along.

"This is a very difficult case," Justice Peter Lauwers, who had been appointed by the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, wrote for the court. As he saw it, the most damning fact - the one that tipped the balance - was that the Crown had shown no initiative when the multiple-murder Shafia case had been tying up Kingston courtrooms. "The Crown did not have any explanation for why no one approached the Regional Senior Justice to see what other arrangements could be made to accommodate this trial under those circumstances, such as utilizing other venues in the Eastern Region."

Ms. Williams, the Crown's prosecutor on the file, declined to comment when contacted for this story.

"With great reluctance," the court erased Mr. Williamson's convictions for buggery, indecent assault and gross indecency, for the repeated assaults on 12-year-old Byron Ruttan.

The Crown appealed to the Supreme Court.

That the criminal courts were a quagmire was not news to the Supreme Court. In 1990, it had issued guidelines (in R v. Askov, a case initially involving extortion and related offences) for how long criminal proceedings should take. Over the next several months, 50,000 charges were thrown out in Ontario alone. Then, in 1992, in R. v. Morin (a case involving impaired driving), the court relaxed those guidelines.

Ever since, trials had become more complex, Charter rights more fully developed, the Crown duty of disclosing evidence to the defence more burdensome. Provinces set up high-level task forces to tackle the growing problem of delay, but in many jurisdictions, delays stretched ever longer.

Now, all these years later, the cases of Mr. Williamson and Mr. Jordan were before the court.

Mr. Jordan had been found guilty of dealing hard drugs over the phone in Surrey and Langley, B.C. The charges against him had taken four years to reach trial, yet the trial judge and B.C.'s highest court had deemed the long delay in his case acceptable.

Mr. Jordan's lawyer, Eric Gottardi, reminded the Supreme Court that the right to timely justice extends back 800 years, to Magna Carta, in England.

All nine judges on the Supreme Court agreed that the delay was intolerable, and threw out Mr. Jordan's conviction. Five said that the 1992 guidelines had created "a culture of complacency," and that the lower courts' acceptance of the four-year delay in Jordan proved their point.

One of those five (and the ruling's co-author, with two of his colleagues) was Justice Moldaver, whose tough decisions at a lower court had done so much to increase prison terms for people who prey on children. Criminal-justice delay was his pet subject; a Harper appointee, he had given lectures about it while an appeal-court judge, even invoking Peter Finch's mad-as-hell speech in the movie Network.

He and the other four judges in the majority set out to remake the system. Seriousness of an offence would, they wrote, no longer matter when deciding if a delay had been unreasonable; all accused have the same rights. Every delay caused harm, whether actual or inferred; no longer would accused people like Mr. Jordan have to prove such harm.

Most important, the majority wrote new time limits: 30 months for Superior Court, and 18 for Provincial Court. Beyond that, criminal proceedings would now be presumed to be too long.

To meet the new demands, the system would have to change in a hurry. The majority even suggested an end to preliminary inquiries, as a starting point.

But they included an important exception: Cases under way before this new ruling - that is, prior to July of 2016 - fell into a "transitional" period. If the Crown had reasonably relied on the rules as they had been, legal proceedings that carried on beyond the new time limits could still be deemed justified. That way, the justices said, there would be no repeat of the chaos that had followed the court's Askov ruling in 1990. Williamson was just such a transitional case.

But there was still that damning conclusion of the appeal court - that the Crown had not looked for alternative courtrooms. In fact, that is what ultimately settled it. The majority, this time six judges, wrote that the Crown "made no effort" to find answers to the delay. (The other three judges, besides the co-authors, Justice Russell Brown and Justice Andromache Karakatsanis, were Justice Rosalie Abella, Justice Suzanne Côté and, in a brief, separate concurrence, Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin.)

The three dissenting judges were dumbfounded. The appeal court's criticism of the Crown, wrote Justice Thomas Cromwell, joined by Justice Richard Wagner and Justice Clément Gascon, was "procedurally unfair, and speculative given that the trial judge had accepted the effect of the [Shafia murder trial] on the institutional resources in Kingston and that there was no evidence that there were any alternatives or that they could have been effective." Also, given that Mr. Williamson had been convicted of serious crimes against a child, and that the delay, while excessive, had not been extreme (they put it at 30.5 months), they said that the conviction should stand.

The majority was just as flabbergasted that the dissenters would mention the guilty verdict, writing that it had nothing (it even italicized the word) to do with the issue at hand. In the end - professing "great reluctance," as had the appeal court - the majority killed, forever, the prosecution of Mr. Williamson for crimes against Mr. Ruttan. "This case," they wrote, "is an example of how delay works to the detriment of everyone."

Mr. Ruttan could not have agreed less. As he put it to The Globe and Mail: "Maybe they should put themselves into the spot that I was in, instead of his spot, and his well-being."

Mr. Williamson declined to comment for this story. But court documents and his own correspondence with a teacher-certification body provide some details about him.

He retired as a teacher after the jury convicted him in 2015. An avid cyclist, while awaiting sentencing he wrote a book about his adventures in bicycling. When the Ontario College of Teachers scheduled a disciplinary hearing late last year, he declined to participate, saying in an e-mail to the college that he was financially secure on a full teachers pension and had no intention of renewing his certification. The college, after hearing testimony from Mr. Ruttan, revoked his teaching certification.

Because the guilty verdict was thrown out, Mr. Williamson is likely not covered by the National Sex Offender Registry. (His lawyer, Sean May, said he believes he is not covered; the RCMP, which oversees the registry, referred the question to Public Safety Canada, which did not provide an answer.)

A good father, with loving sons

Today, ready to make public that which he had been unable to cry out against all those years ago, Mr. Ruttan seems more at peace than he was last winter. "I'm not going to sit there all my life and be mad at the world," he told The Globe, shortly after Justice Tranmer lifted the publication ban on his identity. "What good does it do you?"

His youngest son, at 10 years old just short of the age Byron was when assigned his mentor, deserves some of the credit, says Mr. Ruttan's eldest son, Bryon. "He's our family psychiatrist. He sees Dad getting frustrated and he'll make him talk about what's bugging him. He's grown up with grown-up conversation." The little boy's constant refrain to his father: "Are you going to let that wreck your day?"

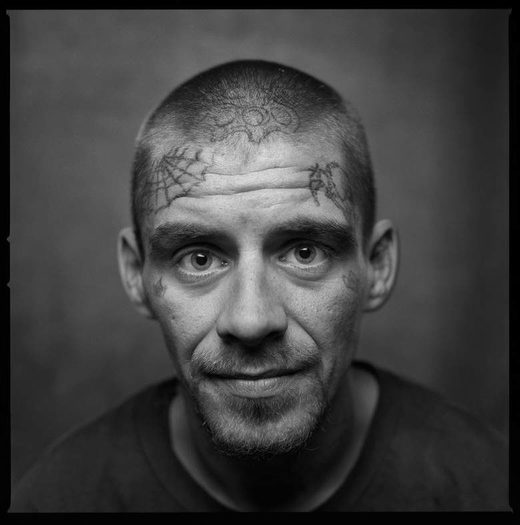

The sins committed against the father have deeply affected the next generation, as Bryon sees it. Bryon, who has children of his own, has a criminal record, which includes violence, and is dealing with his own anger. (The similarity in their names once even meant that the jail he was in gave him his father's meds by mistake, he says, and he woke in the morning with no memory of the night before.) He is struggling to turn his life around - "to grow up," as he puts it - and to be a presence in his own children's lives.

"We become products of our environment, I guess," says the heavily tattooed son. "First you've got to realize it, and then want to change. For Dad, though, it's different. It's deep, embedded issues in his mind I don't think he'll ever come to terms with."

Still, when asked to describe Byron, he offers this short summation: "He's my hero." And as a father? "Really big-hearted. An awesome Dad. He'd ground us, and then give us money so we wouldn't be mad at him for grounding us."

"He always struck me - typical of many of my clients - as, I don't know if it's empty or sad or something, but with that glimmer of hope," says his civil lawyer, Simona Jellinek of Toronto. (In an unusual event, a juror contacted Mr. Ruttan after the trial, and then, over doughnuts in the rural community of Harrowsmith, referred him to a local lawyer, who in turn referred him to Ms. Jellinek. Mr. Ruttan is now suing the Ontario government for $2.85-million, alleging that it failed to properly screen and supervise Mr. Ruttan's mentor. He is also suing Mr. Williamson himself. No trial date has been set.)

In the end, as his youngest son might say, he has not let his experience with the criminal justice-system ruin all his days.

"There might not be justice out there for me - for him," says Mr. Ruttan, referring to Mr. Williamson. But then he adds this: "I'm now here to tell anybody that wants to know, that's going through the same thing, that there is a light. It's difficult to see, but it's there."

And where there is light, there may yet be some luck.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter