To keep them from fighting back, he smashed their heads with rocks and wrapped his hands around their necks. Sometimes he threatened them with a gun.

Police became frustrated, unable to identify him even though they had his DNA from the crimes. Desperate for a break, they checked a database of convicted felons, but came up empty-handed.

Finally, they searched for a partial match to see whether he had a relative in the database. They got lucky — the man had a brother in custody, which led authorities to the assailant.

The "Roaming Rapist" is one of a handful of cases that California authorities have quietly solved in recent years using a controversial technique that scours an offender DNA database for a father, son or brother of an elusive crime suspect.

The state's early success using familial DNA searches to identify the so-called "Grim Sleeper" serial killer led Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck to predict that the method would "change the way policing is done in the United States." Civil liberty groups expressed alarm, saying the searches raised significant ethical and privacy concerns. Some questioned their legality.

Since then, familial DNA has made more modest progress than Beck predicted but has also gained wider respect. Eight other states have followed California's lead, formally embracing the technique as a crime-fighting tool. And though many opponents still express concerns, California's approach has won over some previous skeptics who say they are impressed with the state's strict policies limiting its use and the measured successes.

Using the method helped detectives in the state identify two murderers, including the Grim Sleeper, and five men wanted for sexual assaults, according to the attorney general's office.

Early last year, authorities arrested a San Diego County man accused of sneaking into children's bedrooms and cutting holes in their pajamas before molesting them. A few months later, a Vacaville man was arrested on suspicion of raping and sodomizing a woman along a bike path.

A Santa Cruz County judge in 2013 sentenced a man to life in prison for raping a coffee shop employee then barricading her inside a walk-in refrigerator.

Lab officials look for a relative by scanning genetic profiles in the offender database and looking for DNA samples that match with a suspect's along several, but not all, markers. From there, California's testing method focuses on part of the Y-chromosome passed down along the male line, identifying father-son or full brother relationships.

As more genetic markers for people's DNA are entered into offender databases, the technology will become more precise, said geneticist Frederick Bieber, a professor at Harvard University's medical school and a leading authority on the technique. That could help officials identify more distant relatives and track down criminals who aren't in the system, he said.

"The technology is powerful...there's demonstrable success," Bieber said.

Britain pioneered the use of familial DNA for crime solving more than a decade ago.

In one of the earliest cases, detectives reopened the 1988 killing of a 20-year-old woman in Wales and compared DNA from the assailant to genetic profiles in Britain's database of known offenders. In 2002, they got a partial match to a 14-year-old boy. The teen wasn't alive at the time of the slaying, but detectives used the clue to focus on his uncle, who eventually pleaded guilty to the murder.

Despite that conviction and others, the technology took some time to catch on in the U.S. and was used only sporadically. Among its earliest uses was the 2005 Kansas arrest of Dennis Rader, the BTK serial killer, which came after officials subpoenaed a tissue sample from his daughter's Pap smear taken at a medical clinic.

Gov. Jerry Brown — then the state's attorney general — began fielding letters and visits from prosecutors, urging him to consider using familial DNA. His advisers, however, were concerned approving the method might cause federal judges to shut down the whole database on constitutional grounds.

In 2008, Brown enacted a comprehensive familial DNA policy — making California the first state in the country to do so.

Under the policy, familial DNA is only to be used as a "last resort" when all other investigative angles have been exhausted. So far, the state Department of Justice has run 156 familial searches, many of them repeat queries, such as in the Grim Sleeper case.

An initial search turned up nothing, but state officials ran another scan in 2010. A partial match came back to a man added to the database after a 2008 arrest for firearm and drug offenses. Detectives zeroed in on the man's father, Lonnie Franklin Jr., who lived close to where many of the victims' bodies were dumped in South L.A.

Detectives believe Franklin killed at least 25 women over more than two decades. He was sentenced to death in August.

Nabbing Franklin changed things for now-UCLA Law School Dean Jennifer Mnookin, who once condemned using DNA to find suspects by searching for relatives. Mnookin argued that the method invades privacy rights and is racially discriminatory because African Americans and Latinos are disproportionately represented in DNA databases.

Although she still worries about the racial disparity, she said her view shifted after seeing the effect on big cases, such as Franklin's, and how infrequently the technology is used.

"If it's helping us solve big cases," Mnookin said, "it seems like a worthwhile trade-off."

Eight other states — Colorado, Wisconsin, Virginia, Michigan, Texas, Wyoming, Utah and Florida — have protocols for the use of familial DNA, and the technology has also been used informally by agencies elsewhere.

But the growing popularity of the technique has raised alarms for some privacy advocates, such as Steve Mercer, chief attorney for the forensic division of the Maryland Office of the Public Defender. Mercer successfully lobbied for his state's formal ban on familial searches. Washington, D.C., is the only other jurisdiction to prohibit them outright.

Searching for relatives through partial matches is intrusive, he said, and raises concerns about the 4th Amendment's prohibition on unreasonable search and seizure.

"It is a slippery slope," he said.

Critics also warn that partial matches can point authorities to innocent people. In 2014, the technology led police in an Idaho city to wrongfully suspect a New Orleans filmmaker of committing a notorious 1996 murder.

Police homed in on him after examining an online database of genetic profiles. One profile, which was a near match to DNA left at the crime scene, belonged to a man who had donated his DNA years earlier to a hereditary studies project conducted by the Mormon church. An ancestry research company purchased the program's database, making it publicly available.

Idaho Falls police obtained a court order compelling the company to turn over the identity of the man, who detectives thought could be related to the killer. Once they had his name, they scrubbed his family and focused on the man's son, Michael Usry.

Detectives flew to New Orleans and interrogated him for more than three hours, before ordering him to provide a cheek swab. Usry asked whether someone he knew had committed a heinous crime. No, the detectives told him, they were looking at him.

He waited anxiously for a month, wondering whether he'd be wrongfully arrested. Finally, an email came.

"Mr. Usry," it read, "your DNA did not match with our case. Sorry for the inconvenience."

The science is complicated and his experience shows it isn't the "perfect system" some supporters make it out to be, said Usry, now 37 and living in Colorado.

"I'm still just scratching my head," he said. "Civil rights are being taken from us at an alarming rate."

Still, supporters of familial DNA searches point to its successes.

Sacramento's "Roaming Rapist," Dereck Sanders, spent 14 years on the loose, attacking women in the late-1990s and early-2000s. He sexually assaulted 10 victims, including two teenagers,14 and 15, who sneaked out one night to meet up with friends.

Officials ran his DNA and began trailing Sanders, whose brother — a convicted rapist — was in the offender DNA database. Sacramento sheriff's deputies followed him to a McDonald's drive-thru, where he ordered a Happy Meal, and then to a park where he ate and threw away his trash. Detectives retrieved the garbage and took it back to the county's crime lab. There, officials tested the DNA from a straw Sanders had used.

It was a match.

"That was one of the happiest meals we ever had," said Rob Gold, the supervising deputy district attorney who prosecuted Sanders. "It would not have been solved without familial DNA."

Sanders' 14-year-old victim, who is now 33, said the rape destroyed her for years.

She obsessed over maintaining control in all situations and felt paranoid. She watched until her girlfriends walked into their homes and shut the door behind them, but still found herself texting them to double-check that they were safe. (The Times generally does not identify victims of sex crimes.)

She got counseling and tried to understand the different ways the rape had affected her. Still, the same two questions often came to mind. Is he hurting anyone else, she wondered? Will I ever get the chance to look him in the eye?

The answer came in the fall of 2014 at Sanders' trial, where she testified against him. He was convicted of multiple counts of sexual assault and sentenced to life in prison.

To her, the question of whether to use the technology is almost silly.

"It's out there, it's available," she said. "Do it."

Authorities in California have used familial DNA searches to solve several murder and sexual assault cases:

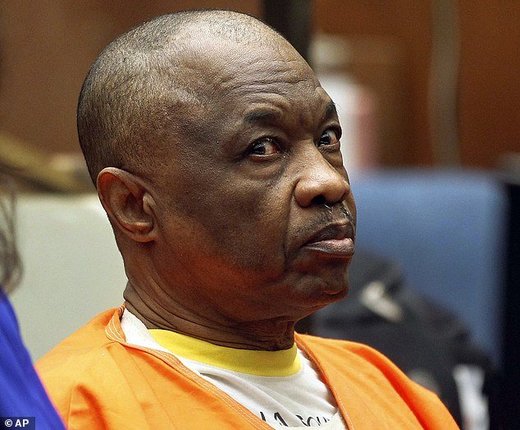

Lonnie Franklin Jr.

The "Grim Sleeper" serial killer prowled the streets of South L.A. for more than two decades. After getting a partial DNA hit to his son in 2010, authorities charged Franklin with killing nine women and a teenage girl. He was convicted earlier this year and sentenced to death.

Elvis Garcia

A man sexually assaulted a barista in a Santa Cruz coffee shop in 2008, threatening her with a knife and barricading her inside a walk-in refrigerator. In 2011, a partial hit to the assailant's father led police to Garcia, who was convicted of sodomy and sentenced to 65 years to life in prison.

James Brown

The 1978 slaying of a 26-year-old woman in an Orange County parking lot remained unsolved for three decades until familial DNA helped lead authorities to Brown, who died in 1996 and had been cremated. Forensic scientists used a DNA sample from his son to confirm Brown was the killer.

Dereck Sanders

Beginning in the late 1990s, the "Roaming Rapist" sexually assaulted women and girls across Sacramento County. Sheriff's deputies arrested Sanders in 2012 after a crime lab got a partial hit to his brother, a convicted rapist. Sanders is serving life in prison.

Michael Simpson

In 2002, a man raped and beat a 55-year-old woman behind a store in Sunnyvale. Using a familial DNA search, police identified Simpson as a suspect. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Gilbert Chavarria

During a heat wave in the summer of 2013, when many people left their windows cracked open, a San Diego County man snuck into the bedrooms of six children and cut holes in their pajamas before molesting them. Authorities said a familial DNA hit ultimately led them to arrest Chavarria. He has pleaded not guilty.

Jeremy Delaunay

In the summer of 2014, a teenager in Vacaville sexually assaulted a woman along a bike path before stealing her jewelry. A year later, authorities arrested Delaunay. He is serving six years in prison after pleading guilty to rape.

Part of the process of SMC development... you simply won't be able to hide anymore... implying that the current PTB better hope their side 'wins'.