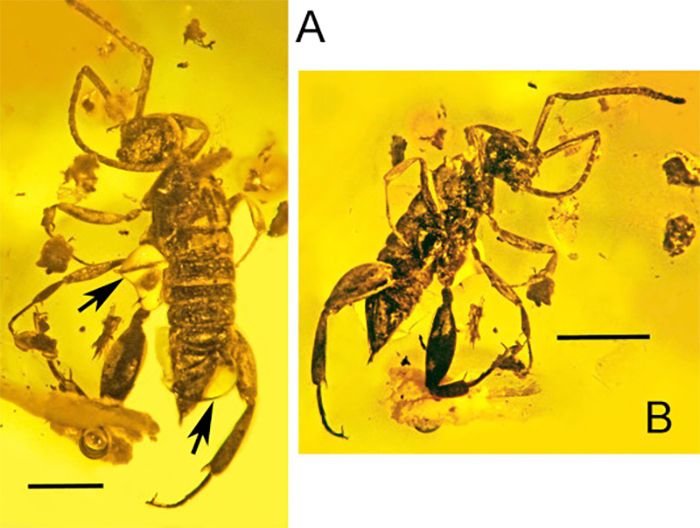

Researchers at Oregon State University have unveiled the preserved remains of an ancient parasitic wasp named Aptenoperissus burmanicus, which has the legs of a grasshopper, the abdomen of a cockroach and the antenna of an ant.

"When I first looked at this insect, I had no idea what it was," professor George Poinar Jr., one of the world's leading experts on life forms found preserved in amber, said in a statement. "You could see it's tough and robust, and could give a painful sting."

As detailed in a paper published in the journal Cretaceous Research , the unusual insect was discovered encased in amber retrieved from China's Hukawng Valley in Myanmar.

Researchers studying the female wasp believe it crawled along the forest floor hunting for insects hidden in crevices and other concealed habitats. When it encountered prey, it would paralyze its victims and lay its eggs. The eggs would then hatch and consume their host alive, much like modern day parasitic wasps do.

According to Poinar, the insect's unique appearance stumped scientists from around the world.

"We had various researchers and reviewers with different backgrounds, looking at this fossil through their own window of experience, and many of them saw something different," he added.

The team eventually took a clue from the insect's wasp-like face and included it as part of the larger order of Hymenoptera, which includes modern bees, wasps and ants. Under this umbrella, they created a new family called Aptenoperissidae, of which A. burmanicus is currently the only specimen.

"We ultimately had to create a new family for it, because it just didn't fit anywhere else," Poinar said. "And when it died out, this created an evolutionary dead end for that family."

As for the insect's demise, the researchers speculate that habitat loss, exposure to pathogens, or perhaps even a lack of wings may have contributed to its extinction. They hope further amber discoveries in the Hukawng Valley will yield new specimens and shed further light on one of the insect world's most bizarre creations.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter