The hulking plant sat vacant until a co-op of Virginia dairy farmers purchased it in summer 2013 to process milk and ice cream, though on a far smaller scale than the 60,000 cases of ice cream that global food giant Unilever churned out every day.

Randy Inman, the board president for Shenandoah Family Farms, said he expected the plant's revival to trigger plenty of interest in its three dozen or so initial jobs. What he did not expect: 1,600 applicants and counting - a deluge.

Many applicants are desperate former employees still without work in a county with 7.3 percent unemployment and in an economy where manufacturing job openings now require more specialized abilities than the lower-skilled positions that have gone overseas or, in the case of Unilever, to Tennessee and Missouri, where labor and operating costs are cheaper.

Wall Street is booming, the Federal Reserve is paring back its stimulus, there are bidding wars for houses again, but for blue-collar workers in places like Hagerstown the economic recovery has yet to materialize, and many around town worry that it won't. Laid-off workers are living week-to-week on unemployment. They're working temp jobs and trying to reeducate themselves. They are trying to save their houses from foreclosure.

A handful of former workers have gotten lucky, returning to their old jobs as the plant begins production later this month. They won't earn as much as they did before, but they aren't complaining. One rehired worker - and his boss - spoke on the condition of anonymity. He is being inundated with pleas for help landing jobs from former colleagues.

"I've been hounded on Facebook," said the 60-year-old mechanic who had been working in lawn care before he got hired back. He has told the job seekers, "Put in a résumé; put in an application."

Brooks, whose unemployment benefits are about to run out, put in two.

"I'd even take a hand-packing job just to start," he said, meaning a job stuffing boxes with ice cream. "I didn't even get a call."

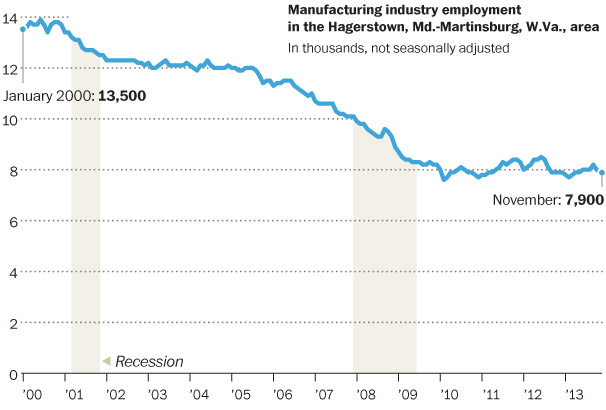

The country lost 6 million factory jobs between 2000 and 2009, and in Maryland, the job losses have been catastrophic. There were about 172,000 manufacturing jobs in the state in 2000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics; today there are about 104,000, a nearly 40 percent drop. In the Hagerstown area, which once produced airplanes, pipe organs and leather car seats, there were roughly 14,000 factory jobs in 2000. Today: about 8,000.

The staggering job losses have the attention - finally, some workers say - of Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley (D), who has revived the dormant Maryland Advisory Commission on Manufacturing Competitiveness. Later this month, the commission is scheduled to release recommendations on improving prospects for manufacturing jobs.

"For us to stay the course would mean continued erosion of middle-class jobs that are very hard to regrow," said Jeff Fuchs, the commission's chairman.

The challenge for elected officials, experts say, is preparing workers accustomed to the manufacturing of the past for what is needed now. New plants feature specialized machines that frequently use complex computer programs - "precision" manufacturing. Such factories require higher-skilled workers but fewer of them.

That's a difficult world for a former ice cream plant worker to enter.

"Workers need to be a step above what their fathers and grandfathers were capable of doing," Fuchs said. "The manufacturing employees of today need to be cross-skilled. They need to know how to do a lot. It's not just monitoring a machine and pushing a button when you're supposed to."

Maryland is investing more money to help workers. The state's new $4.5 million industry-led job training and competitive workforce program, called EARN (Employment Advancement Right Now), last week announced 29 grants for job training programs for a variety of industries, including biotechnology, cybersecurity, green jobs, health care, logistics and manufacturing.

"There is no progress without a job," O'Malley noted in making the announcement.

But reeducating lower-skilled workers is a long process with multiple challenges. Many workers enter job training programs with little to no formal education. Other workers have family circumstances that prevent them from putting in the necessary time to learn new skills. Still more are stubborn and think they will eventually land a job like the old one.

The job training experiences of many former ice cream workers offer a window into the difficulties. The laid-off workers were eligible for up to $4,500 in state and federal assistance for retraining. At the Western Maryland Consortium, a job training group, executive director Peter Thomas said 85 workers enrolled for services including remedial education, computer training and occupational skills development. Forty-nine have landed permanent jobs - as dental assistants, forklift operators, business accounting software workers or truck drivers, which was the largest new occupation for the reeducated ice cream plant employees.

One worker who went through the job training program was starting over after 28 years at the plant as a mechanic. He met his wife on the job. He had been working third shift - the graveyard shift - at the plant for years, and it was taking its toll.

When the plant closed, "I wasn't really depressed," he said. "I was ready for a change."

He got a truck driver's license, but he wound up taking a job working on a dairy farm. There weren't many other options. He was earning $26 an hour making ice cream. He's making $13 an hour now. His wife is studying to be a nurse.

"We have no benefits at all," he said. "We're going to look into the Obamacare thing if we can ever get online to do it."

They have cut back on spending. They've taken some money out of retirement accounts. But, he said, "My health is better because I'm not working third shift. Third shift is a miserable life. I'm happy. As long as I can survive, that's all I really care about."

The dairy co-op is gearing up for production on Jan. 22. It will process milk initially, then add ice cream products - gallon containers, novelty bars, cones. The Virginia farmers and their families will have their pictures on the products. The idea is to connect consumers with the source of their milk and ice cream. How many additional employees will be hired is unclear, but plans are to ramp up fast.

Inman, the co-op board's president, knows that many former workers are desperate to come back. In the lobby the other day, inside the local newspaper box, the main headline on the front page read: "Long-term jobless benefits at end?"

"We would like to be able to hire some more of these people back," he said.

oh well, maybe i can sell green energy, or maybe i can rent my brothers bedroom room, and hope my mom and dad dont notice, or maybe i can make cool graphix for websites, or maybe i can dig ditches, or maybe i can get two pizza delivery jobs, they havent cancelled my insurance yet.. maybe i can get one more bartending gig, and hope i get in the movies.

or maybe, this one dollar will win us the lotto, or maybe if i rewrite my resume on linkended,and monster, maybe then i will get the call. or maybe.........