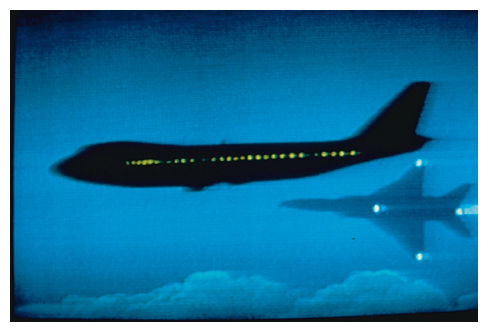

© Getty Images/Fotobank

In the early hours of the morning, some 30 years ago and at the height of the cold war, Soviet fighters were ordered to scramble and intercept a Boeing 747 passenger jet in the skies above Sakhalin.

A few hours later, on September 1, 1983, Korean Airlines flight 007 was shot down west of Sakhalin Island, in the Sea of Japan, known to Koreans as the East Sea, killing 269 passengers and crew.

Following a lengthy investigation, the International Civil Aviation Organisation found that the 747 had accidentally strayed into Soviet airspace. But it condemned the Soviet Union for shooting down the aircraft.

However, the controversy continues. The official explanation, which the governments of at least four countries - South Korea, Japan, Russia and the United States - adhere to, said the Korean Airlines Boeing 747 was on a routine flight from New York to Seoul, with a refuelling stop in Anchorage, Alaska.

Its route lay above the Pacific Ocean, skirting Soviet territory. However, right from the take-off in Anchorage the aircraft began to deviate from its course. By the time it was shot down to the southwest of Sakhalin, the Boeing 747 was some 500km off its intended route.

At 4:51am local time the aircraft entered Soviet airspace above a restricted area in Kamchatka, where a Soviet nuclear missile base was situated.

According to the official explanation, the Soviet air defence mistook the Boeing for a US RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft, which was reportedly monitoring the launch of a Soviet ballistic missile on the same night. On radar screens, an RC-135 looks exactly the same as a passenger Boeing.

MiG-23 fighter jets were scrambled to intercept the Korean aircraft above Kamchatka and accompany it until it left Soviet airspace.

However, at 6:13am, the Boeing crossed the Soviet border again, this time above Sakhalin. Su-15 interceptor aircraft were dispatched to deal with it. At 6:24am, fighter pilot Gennadi Osipovich launched two missiles that hit the aircraft.

The wreckage fell into the sea from an altitude of nine kilometres near the island of Moneron to the southwest of Sakhalin. According to the official report, the incident was a result of a series of coincidences.

However, those who were involved in the events on the Soviet side point to numerous inconsistencies, indicating that the Boeing entered Soviet airspace not by accident, and they continue to question the official explanation of what really happened.

The former Soviet military leadership, says the Boeing entered the country's airspace on a reconnaissance mission aimed at gathering information on radar installations in the Soviet far east. It should be noted that considerable areas of the Soviet far east were restricted territory.

The first question that the Soviets asked was how the aircraft could have deviated so much from its course.

The Boeing 747 was equipped with the most advanced navigation systems of its day, serving as a backup for each other. Furthermore, it is unusual for US and Japanese air-traffic controllers not to make any attempt to get in touch with the KAL-007 flight to tell the crew that they were off course.

The second question is whether there were passengers on board the aircraft. Unlike in other air crashes, a passenger list was not published following the disaster.

"

The Koreans were supposed to publish the list of passengers. That did not happen. Who then can claim that there were passengers there?" says test pilot and military expert Aleksandr Shcherbakov.

Only 30 body parts were found at the scene of the crash, despite the fact that there were more than 200 people on board. "

I am convinced that they were not there.They could not have disappeared or dissolved in seawater," says Anatoly Kornukov, who in 1983 headed the 48th Fighter Aviation Division of the Far East Military District.

Filipp Bobkov, who in 1983 served as a deputy chairman of the former KGB, said it was "

a carefully planned operation. There were no passengers, just the crew," he says.

The theory that the flight was a reconnaissance mission, Soviet officials believed, was further strengthened by a seemingly insignificant 40-minute delay that the aircraft had in Anchorage.

The delay in itself is a common enough and does not raise any questions. However, it allowed the aircraft to enter Soviet airspace simultaneously with the US Ferret-D/Farrah satellite.

"

Its departure was adjusted to coincide with the approach of a US satellite. The whole of the air defence system of the Soviet Far East was exposed," says Vasily Alekseyev, who in 1983 headed the Air Force counterintelligence division at the USSR Defence Ministry.

According to Ivan Tretyak, who in 1983 served as the commander of the Far East Military District, Soviet intelligence intercepted a coded message sent from the Boeing to the satellite saying, "

am seeing submarines deep underwater. Visibility good. Am taking pictures."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter