© economonitor.com

The White House and the nation's most prominent charities are embroiled in a tense behind-the-scenes debate over President Obama's push to scale back the nearly century-old tax deduction on donations that the charities say is crucial for their financial health.

In a series of recent meetings and calls, top White House aides have pressed nonprofit groups to line up behind the president's plan for reducing the federal deficit and averting the year-end "fiscal cliff," according to people familiar with the talks.

In part, the White House is seeking to win the support of nonprofit groups for Obama's central demand that income tax rates rise for upper-end taxpayers. There are early signs that several charities, whose boards often include the wealthy, are willing to endorse this change.

But the White House is also looking to limit the charitable deduction for high-income earners, and that has prompted frustration and resistance, with leaders of major nonprofit organizations, such as the United Way, the American Red Cross and Lutheran Services in America, closing ranks in opposing any change to the deduction.

"It's all castor oil," said Diana Aviv, president of Independent Sector, an umbrella group representing many nonprofits. "And the members of the nonprofit sector I represent don't want any part of it. It's a medicine we're not willing to drink."

The dispute is the latest in a long-standing struggle over the popular tax provision, which allows people to deduct charitable donations from their taxable income. The battle is playing out at the highest levels of government and in the corridors of K Street.

Since Obama first proposed to lower the deduction in 2009, more than 60 nonprofit groups have spent at least $21 million lobbying Congress and the White House to preserve it, lobbying records show. Although nonprofit officials characterize the effort as grass roots, including a recent "Lobby Day" during which the groups' staffers donated their time and descended on Capitol Hill, at least 25 organizations have hired Washington area lobbying firms.

The lobbying by some of the biggest players in the philanthropy world has intensified in recent weeks amid spreading concern over whether the charitable deduction could be affected by a deal to avoid the automatic spending cuts and tax increases set to kick in Jan. 1. Nonprofit group leaders say lowering or eliminating the deduction would reduce giving by wealthy donors. Studies have shown that people would donate less if the deduction were reduced, but estimates of the effect vary widely.

"It would be devastating," said Jatrice Martel Gaiter, executive vice president for external affairs at Volunteers of America, which has paid Patton Boggs - Washington's most lucrative lobby shop - nearly $200,000 to lobby on the charitable deduction and other issues in the past year. "Of course people want to say they are giving out of the goodness of their hearts, and of course they are, but the tax deduction makes our hearts larger and our goodness even better."

Nearly 40 million people a year claim the deduction on individual tax returns, according to congressional estimates. Because it costs the government so much tax revenue - about $230 billion between 2010 and 2014, according to Congress's Joint Committee on Taxation - proposals to limit this and other deductions have emerged as concern has grown over the government's finances.

Obama has proposed capping the value of tax deductions for individuals earning more than $200,000 ($250,000 for families) at 28 percent, regardless of their tax bracket. This would include deductions for mortgage interest and state and local taxes, along with charitable contributions.

The tax code allows people who itemize deductions to deduct their charitable contributions at their maximum marginal tax rate. So, for example, if someone in the highest tax bracket - now a 35 percent tax rate - gives $100 to charity, the donor saves $35 in taxes. If the deduction were capped at 28 percent, the donor would save only $28.

Capping deductions at 28 percent - including those for charitable contributions, mortgage interest, and state and local taxes - would raise $574 billion in new federal tax revenue over 10 years, according to White House estimates. The White House did not detail how much revenue would be produced specifically by lowering the charitable deduction.

Obama has dismissed the charities' contention that his plan would substantially damage their fundraising. White House officials, including Chief of Staff Jack Lew and senior adviser Valerie Jarrett, have recently been telling nonprofit leaders that they would face far graver danger under Republican deficit-reduction plans.

The White House's sessions with the leaders of charitable groups reflect a broader strategy to marshal support from a variety of outside interest groups for raising marginal tax rates for high-earning Americans. Obama has called for allowing George W. Bush-era tax cuts on the wealthy to expire at the end of the year, while Republicans have said that new tax revenue should be raised by closing loopholes and deductions. The administration's aim is to apply pressure on House Republicans to accept Obama's tax-rate plan.

Obama aides this week also signaled a willingness to overhaul corporate taxes as an enticement for the chief executives of major U.S. companies to speak out in favor of raising individual income taxes, and a number of prominent executives have begun backing the tax plan in recent days.

The efforts to press charities have been bumpy. Although many nonprofit leaders agree with Obama's view on top-end tax rates, they have been disappointed that the president seems unwilling to drop his plan for limiting the charitable deduction.

The frustration stems in part from what some nonprofit leaders describe as a philosophical disagreement between Obama and the nonprofit sector. The president has framed the tax deduction as a benefit for the wealthy, they say, while in their view, the deduction is a benefit for charities, which use the money to help the needy

Stacey Stewart, president of the United Way, cited a "disconnect" between the White House and charities. Stewart said she and others listened to the White House argument but were not willing to waver in their opposition to an "assault" on the charitable deduction.

White House officials have warned publicly and privately that Republicans would "eliminate" the charitable deduction altogether by placing caps on total deductions and rejecting higher tax rates, which represent an alternative source of revenue. Obama made this argument during an interview on Bloomberg Television last week, painting the GOP as the party that would hurt charities.

"There's been a lot of talk that somehow we can raise $800 billion or $1 trillion worth of revenue just by closing loopholes and deductions, but a lot of your viewers understand that the only way to do that would be if you completely eliminated, for example, charitable deductions," Obama said.

"Well, if you eliminated charitable deductions, that means every hospital and university and not-for-profit agency across the country would suddenly find themselves on the verge of collapse."Aides to House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) dispute the White House's characterization. They say House GOP leaders have signaled their desire to negotiate with Obama on all deductions, including the one on charitable giving.

"There are more than enough loopholes and tax shelters for the wealthy that can be pared back without going any further than the president's own proposal to limit charitable deductions," said Boehner spokesman Brendan Buck.

When the president initially proposed reducing the charitable deduction in 2009, originally to help pay for his health-care overhaul initiative, he said there was "very little evidence" that the change would significantly affect giving. Speaking at a news conference, he said the deduction "shouldn't be a determining factor as to whether you're giving that $100 to the homeless shelter down the street."

His proposal helped trigger the lobbying campaign to preserve the current deduction. The effort has involved an array of nonprofits representing artists and musicians to museums, universities and religious groups. Some of the best-known nonprofits - including the YMCA of Greater New York, the Boy Scouts of America and the Philanthropy Roundtable - have hired D.C. lobbying firms.

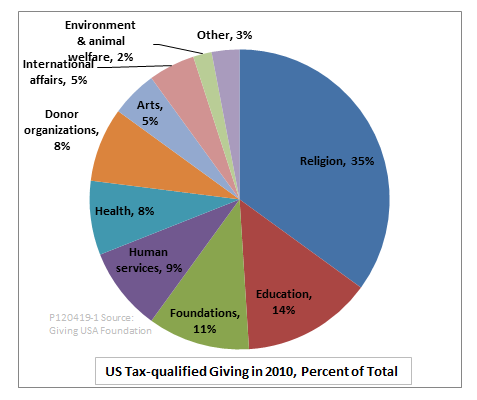

The charities characterize the lobbying expenses as a sound investment given the money at stake: Americans donated nearly $300 billion to charity last year. The groups say they had to act because lowering the deduction would reduce giving, primarily by the wealthy donors who make the bulk of contributions. With their finances squeezed by the economy and state budget cuts, charities say this would force them to cut funding for services such as aid to the poor and artistic programs.

"You don't need to be a Nobel economist to figure out that if you lost the deduction, people would have less of an incentive to give," said Kenneth Kies, a prominent Republican corporate tax lobbyist. His firm, the Federal Policy Group, has been paid more than $600,000 since 2009 to lobby on the charitable deduction and other issues by the Council on Foundations, a leading philanthropy group.

But Kies acknowledged that "no one knows exactly" how much reducing the deduction would affect giving.

A report last year by the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University concluded that the effect of Obama's proposals to reduce the charitable deduction and raise tax rates for the wealthy would be a "relatively modest decline" of up to 1.3 percent in itemized giving, or $2.43 billion a year. Other estimates have ranged as high as $7 billion a year.Some in the sector are skeptical that there would be any significant change.

"People give from the heart," said Jack Shakely, who headed the California Community Foundation, a large nonprofit, for 25 years. "They are grateful for the deduction if they can take advantage of it, but can you imagine if you normally gave $1,000 to a university and you gave them a check for $910? You would look like a jerk, and people know that."

Alice Crites and Lori Montgomery contributed to this report.

Comment: Why not reduce the Pentagon budget?

A New Record is Set for Military Spending: The Shame of Nations

Why is the Most Wasteful US Government Agency Not Part of the Deficit Discussion?