The report, from Pew Center on the States, finds that the gap has widened considerably in recent years, as states have been slammed by investment losses stemming from the 2008 financial crisis and budget crunches caused by the recession.

As of the 2010 fiscal year, the study found that states have about $757 billion less than they need for pension obligations. The states have about $2.31 trillion set aside, the report found, but their liability is about $3.07 trillion.

In addition, the report found that states have a health care liability of about $660 billion, but have set aside only $33.1 billion for those benefits. That leaves a $627 billion gap.

The two shortfalls add up to $1.38 trillion for the 2010 fiscal year, the most recent data available. That's an increase of $120 billion, or 9 percent, from the 2009 fiscal year.

Some say even those massive estimates fall woefully short. Josh Rauh, associate professor of finance at Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management, estimates that states are facing a shortfall of $4.4 trillion for pension obligations alone.

Rauh said that's because most states forecast on the assumption their investments will yield an 8 percent return. As anyone who's watched their 401(k) accounts rise and fall over the past 10 years knows, that's hardly guaranteed.

"That is simply not a valid way to do financial accounting," Rauh said.

David Draine, a senior researcher with Pew Center on the States, said the financial crisis and recession have played a big role in creating the shortfall, but he noted that the problem began before that.

"Many of these states also failed to make recommended contributions when times were good," he said.

Draine compared the situation to a person who owes a lot in credit card debt but is only making the minimum payments, if that. That can work for a while, but the balance keeps growing.

That's how it is with many states right now. They have enough money to pay their current retiree benefits but not necessarily those due in the future.

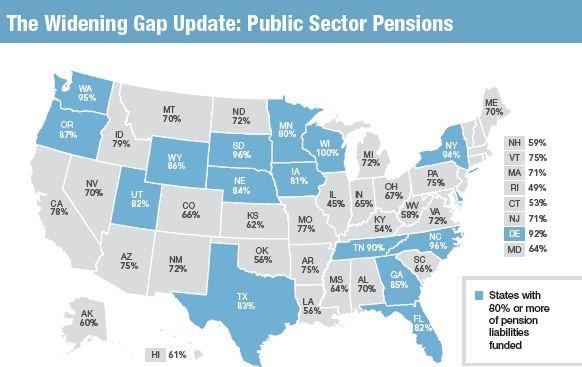

Generally speaking, a healthy pension fund should be 80 percent funded. The report found that 34 states were below that threshold in fiscal 2010, up significantly from 22 states just two years earlier.

The states in the worst shape as of 2010 include Connecticut, Illinois, Kentucky and Rhode Island. The states in the best shape include North Carolina, South Dakota, Washington and Wisconsin.

Many states are completely unprepared to pay for future retiree health care benefits. The report found that 17 states have not set aside any money for that.

Richard Kaplan, a law professor at the University of Illinois who has studied this issue extensively, said it's common for states to have set aside little or no money for retiree health care.

That's partly because they aren't obligated to, and partly because it's very difficult to anticipate what an employee's health care needs might be, let alone what it will cost.

Kaplan said most states have a legal or contractual obligation to make pension payments. But there are far fewer safeguards when it comes to health benefits.

"There is really nothing that is stopping a state or local government from saying this is too expensive or we're not going to cover this anymore," Kaplan said.

Many states are taking action to deal with these budget shortfalls. The Pew report, citing the National Conference of State Legislatures, said 43 states made benefit cuts, increased employee contributions or both between 2009 and 2011.

Rhode Island has been among the most aggressive, with a plan to cut benefits for both current and future retirees.

Rauh, the Kellogg professor, said many state and local governments are pushing to reduce or dismiss cost of living adjustments for retirees as a way to curb costs.

He said those changes have seemed more palatable than more aggressive changes, such as moving public employees into the types of plans that most private employers now use, which are largely driven by personal investments. There's plenty of evidence that many Americans have not done enough to save for retirement on their own using such plans.

"(The) 401(k) plans in the private sector have not exactly been a resounding success," he said.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter