Some 2,500 years ago, the ancient Greeks coined a new word: 'democracy'. In the city of Athens, whose citizens were allowed to decide their future for themselves, a new political system was taking shape, based on the freedom of the individual.

Athens was the wonder of the age, a shining beacon of literature and philosophy. It could hardly have been more different from its 21st-century successor, sunk in economic gloom and scarred by months of riots and demonstrations.

To anyone who cherishes the legacy of the ancient Greeks, the plight of their modern-day inheritors is nothing less than a tragedy. And yet amid the appalling economic headlines, the flame of freedom still burns in the land that gave democracy to the world.

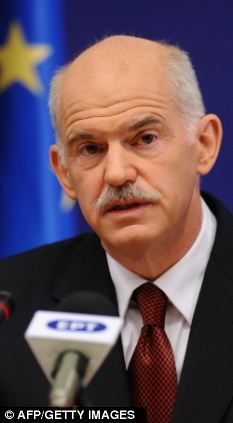

To most European leaders, the Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou's decision to submit the latest bailout to a national referendum is simply incomprehensible.

Brussels insiders have been queuing up to denounce his irresponsibility, insisting the future of the euro is simply too important to be decided by the ordinary men and women of Greece.

Yet despite all the consternation in the markets, it is easy to see why Mr Papandreou felt that he had no choice but to go to the people.

Austerity

On the streets of Athens and Thessaloniki, tempers are close to breaking point.

Under the terms of the European Union's latest bailout, VAT has been raised to 23 per cent, pensions have been cut by 20 per cent and some 30,000 public servants have been put on notice and given a whopping 60 per cent pay cut.

Compared with such astonishing austerity, even George Osborne's record spending cuts look relatively trifling.

And given that Greece's medicine is being administered by the Germans - who occupied the country exactly 70 years ago - you can readily understand why so many Greeks are smouldering with rage.

Only last week, nationwide ceremonies to mark the anniversary of the German invasion were disrupted by demonstrators furious that they were paying the price for the euro's survival.

Against this background, Mr Papandreou decided it was time to let the Greek people choose their economic destiny. As he pointed out, it would be grotesquely unfair to condemn a generation to brutal unemployment without letting the voters decide for themselves.

'We will not implement any programme by force,' he explained, 'but only with the consent of the Greek people. This is our democratic tradition and we demand that it is also respected abroad.'

But if Mr Papandreou was hoping for respect from his European counterparts, he must be sorely disappointed.

For the likes of French President Nicolas Sarkozy, the very notion that the Greeks might want a say in their own destiny is simply intolerable.

'Giving people a voice is always legitimate,' the French President remarked, barely able to suppress his disdain, 'but the solidarity of all eurozone countries is not possible unless each one agrees to measures deemed necessary.'

That little word 'but' is depressingly revealing. Evidently Mr Sarkozy believes that the 'solidarity' of the eurozone is much more important than letting the ordinary voter have his say.

The stark fact is that France and Germany are simply not interested in the hopes and fears of the Greek people. All that matters is to keep the euro alive. And if that means plunging Greece into a decade or more of unprecedented economic agony, then so be it.

But the outrage in the chancelleries of Europe also reflects a much deeper chasm between the leaders and the led.

The truth is that from the very beginning, the European project was conceived and driven by a narrow political elite with a deep horror of democratic populism.

For pioneers such as Jean Monnet, the French bureaucrat who dreamed up the original European Coal and Steel Community in the early Fifties, Europe was never meant to be a populist enterprise. For Monnet and his collaborators, great issues were best decided by well-educated, liberal-minded men in conference halls and committee rooms.

As a result, the great project of European union has never been properly democratic. Even when Britain entered what was then the European Economic Community in 1973, ordinary people were not allowed a say.

Ignoring calls for a referendum, Heath took Britain into the EEC anyway, and then marked the occasion with a gigantic classical music festival - a fitting symbol of an elite-driven enterprise that remained utterly remote from ordinary people.

Notorious

Time and again, the Brussels elite have either sidestepped or ignored attempts to make them accountable to ordinary voters. And even when people vote against the European project, they are compelled to vote again until they give the answer the political classes want to hear.

The most notorious example came in June 2001, when the Irish government asked its people to decide on the Nice Treaty, which allowed the EU to expand into Eastern Europe.

To the utter consternation of their political leaders, the Irish people voted 'No'.

But that was not good enough for the French and Germans, who ordered the Irish government to make their people vote again - and to make sure that this time they voted 'Yes'.

A year later, therefore, the Irish returned to the polls, with their government, the media and the Roman Catholic Church all pushing for a 'Yes' vote. Not surprisingly, Brussels got the result it wanted and democracy was the loser.

But, of course, we in Britain have no reason to feel smug about all this. During the last election, both the Tories and the Liberal Democrats embraced the notion of a referendum on Europe.

Yet when it came to the crunch two weeks ago, David Cameron and Nick Clegg ordered their MPs to vote against offering the public a referendum, claiming that the time was not quite right.

For our political masters, you suspect, the time never quite will be right.

By comparison, Mr Papandreou seems to be a man of rare courage.

The terrible irony of all this is that the European project was meant to be about banishing national hatreds and bringing the peoples of the continent together.

Courage

Instead, it has driven a deep wedge between a tiny elite of politicians and bureaucrats on the one hand, and tens of millions of ordinary people on the other.

If the politicians had the courage to trust the people - as Mr Papandreou is doing in Greece - they might be pleasantly surprised. We often forget, for example, that when the British people were asked to vote on Europe in 1975, two out of three chose to stay in.

Times have changed, of course, and a recent poll suggested that 49 per cent of British voters would choose to leave the EU. But I suspect that if it came to the crunch, a narrow majority would prefer reforming the system to smashing it entirely.

In their sheer contempt for the principles of democracy, Europe's arrogant leaders are undermining their own enterprise. And for the first time in half a century, the future of the European Union itself is in serious doubt.

Greece now faces two months of turmoil, and in January, its people will have a monumental choice. But at least they do have a choice.

And even at a moment of maximum economic peril, the principle of self-determination is worth all the money in the world.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter