Back then, her dream was to become a successful surgeon and to marry a good man.

"I started to dream of the [wedding] gown when I was 10 or 11 years old. I dreamed of forming a small family - having a kid like my mum and to be a surgeon at the same time".

More than 30 years on, Samia is a fully-qualified doctor.

But in a country where the guardianship system means a woman's life is not her own, her dreams of a happy marriage - with a man of her own choosing - have been taken away from her.

Now, as she prepares to take her father before the Saudi Supreme Court, she spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service about her hopes that her experience may pave the way to a "girl rebellion".

Arranged marriage

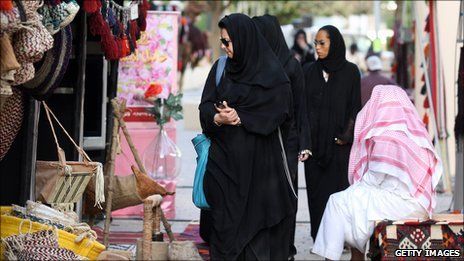

In Saudi Arabia, a highly conservative Islamic state, women must have a male guardian.

Until marriage, guardianship will typically be the job of the father, but this role can be performed by uncles, brothers, and even sons.

Under this tradition, Saudi women must obtain permission from their guardian to work, travel, study, marry, or even access certain types of healthcare.

For Samia, it meant months of trying to persuade her father, a successful businessman, that going to a mixed-gender medical school was a good idea for her future.

"I made a bargain with my parents," she remembers. "I tried to convince them that... if I submitted my papers to the medical school, I will get a big salary, and the salary would be in their hands. They accepted this deal."

As she began medical school, much of Samia's monthly income was taken by her family - but more importantly to her, her choice of male suitor was a decision she was not allowed to make.

Immediately after I stepped out of court, [my father] took me home and beat me, and locked me up in my room for three months""A lot of [colleagues from medical school] had proposed to me," she said. "But they had been refused by my parents for nonsense reasons."

The men were, her father and brothers warned, not from their tribe or were looking to steal her money.

For Samia, there was only one special man, who proposed after she graduated from medical school. Although he comes from a well-known and religious family, and is himself wealthy, her family still refused, she says.

"But I am very attached and I insisted on this guy," Samia says.

Instead, her father found a husband for her - a cousin, she says, who was much younger and less educated than her.

"He told me 'I'm offering you to him'," she recalls.

Locked up

By 2002, aged 33, Samia says her battles with her father were going nowhere.

Eventually, she went to the courts and filed a complaint against him. But, according to Samia, he was able to convince the judge that her chosen marriage candidates were unsuitable.

After the court case, her father and brothers became violent towards her, she says.

"Immediately after I stepped out of court, [my father] took me home and beat me, and locked me up in my room for three months," Samia remembers.

Desperate to get back to her studies, Samia agreed to drop the issue of marriage. By 2006, she had qualified as a surgeon and was earning an impressive wage, most of which was being taken by her family.

By now she was 38 and felt she was running out of time to get married.

Yet, just as before, approaching her father about the possibility of granting permission for marriage was met with anger. Samia was once again locked in her room for months - her father telling the hospital where Samia worked that she was mentally unstable.

It was then that one of her sisters managed to smuggle a mobile phone into Samia's room. She rang a human rights society, which told her to send a letter asking for help. She threw the letter out of her first-floor window to a friend waiting below.Representatives from the rights group came with the police to rescue her from her father's home in the city of Medina, she says. They placed her in a government shelter in another Saudi city and helped Samia take her case back to court. Again, she lost.

She now works as the duty doctor at the shelter on wages well below what she would earn as a surgeon. But she fears that her family would track her down at a hospital.

After telling a journalist her story, news of her plight spread across Saudi Arabia and a lawyer agreed to take on her case pro-bono.

After years of failed appeals, Samia and the human rights society are gearing up to face the Saudi Supreme Court which, according to Amnesty International's Saudi Arabia researcher Dina el-Mamoun, will be a tough battle.

"It's difficult to win these cases because there are no clear guidelines in terms of what they have to prove. The judges have huge discretion in relation to these cases. The outcome really depends on which judge gets the case and who rules on it," says Ms Mamoun.

Samia's case is not a one off. Across the oil-rich desert kingdom, dozens of women are taking guardianship grievances to court. And they are gaining public support.

"I think in terms of public opinion, you do see a lot of sympathy with these women," says Ms Mamoun.

Samia, now 43, is still clinging to her childhood dream of having a family. Her special man, she says, is waiting for her and fighting bravely alongside her.

"I'm still dreaming," she says. "The flame will be alive until my death."

*We have withheld Samia's real name for privacy reasons.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter