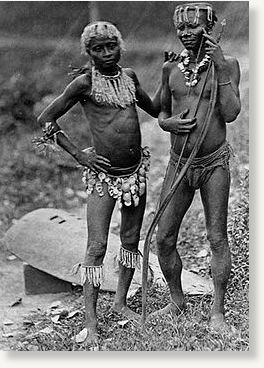

© UnknownTwo Great Andamanese men, in an 1875 photograph

Governed by India, the archipelago separates the Bay of Bengal from the Andaman Sea. The islands are home to several hunter-gatherer tribes who until fairly recently have had very little contact with the outside world.

Anthropologists initially feared the tribes could have been completely wiped out. But Indian Air Force pilots flying sorties over the islands days after the tsunami reported seeing men who fired arrows at their helicopters. Since then there have been reports that the islanders used their ancient knowledge of nature to escape the tsunami.

Bernice Notenboom, president of Moki Treks, a travel company specializing in indigenous cultural tourism, is one of the few outsiders to have visited the tribes. She tells

National Geographic of her impressions from her visit in April 2003.

How did the indigenous islanders fare in the tsunami? What have you been able to tell so far?Due to its remoteness, it took several days before reports came out about the dead and missing in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The first reliable reports on the fate of the Andamanese tribes indicate that most have survived.

Their awareness of the ocean, earth, and the movement of animals has been accumulated over 60,000 years of inhabiting the islands. Oral history teachings and their hunter-gatherer lifestyle might have prepared them to move deeper into the forests after they felt the first trembles of the earthquake.In contrast, the Nicobarese were badly hit. The southernmost island was only 260 miles (418 kilometers) from the epicenter and suffered a series of aftershock earthquakes not one of them less than magnitude 6 [on the moment-magnitude scale] in the days following the big shake. Tens of thousand people are missing and feared dead.

Anthropologists were concerned that in addition to the human tragedy and utter devastation, one of the casualties might be the extinction of some of the very ancient indigenous cultures occupying the islands. What can you tell us about these tribes? Where did they come from?The tribes present something of an enigma to anthropologists. The four Andaman tribes - the Great Andamanese, Onge, Jarawa, and Sentinelese - are known as the Negrito tribes and are of African descent. [Editor's Note: DNA evidence suggests these people might be the ancestors of some of the earliest humans to come out of Africa. Some scientists believe the Negrito residence in the islands goes back more than 30,000 years, possibly as far back as 60,000 years.] Those living on the Nicobar Islands - the Shompen and Nicobarese - are of Asian descent.

The Andamanese are hunter-gatherers who until 50 years ago lived mostly in isolation, with little interaction with the outside world. Now, with recent encroachments and settlers penetrating their lands, they have been forced to withdraw farther in the forests. Threatened by disease, overpopulation, Western influence, and lack of resources, most tribes on the islands are endangered and their numbers have dwindled to just a few hundred.

In contrast, the Nicobarese have become more assimilated and their lifestyles are more similar to those of mainland India. The indigenous Nicobarese have almost completely converted to Christianity. They became horticulturists and herders of pigs.

Are the islands beginning to promote tourism or are visitors discouraged?The Andaman Islands have been restricted [in the past] for non-Indians, but in the last ten years, 38 of the islands have opened up for limited tourism. Regulations under the Tribal Reserve Act, originally passed in 1956, allow only aboriginals to enter the tribal lands. No one can exploit the resources, conduct trade and business, or settle on tribal property.

Once when strolling the streets of Car Nicobar, where billboards, time, and fast food do not exist and the Internet is as foreign as snow, an old Nicobarese man came up to me and said: "It is great to have you here, but let's not make it a habit."

How did the influx of mainlanders affect the tribes?Contact with the outside world has proved to be disastrous. An epidemic of measles in 1999 wiped out 10 percent of the Jarawa population and recently Hepatitis B has been contracted. Disease, corruption, and violence have reduced the number of Jarawas to 250.

Arief Mustafa, my guide while I was there, told me, "Jarawa people have no immune system. If you give them a cotton T-shirt to wear, they will get Western diseases through the fibers of the T-shirt. It transmits disease through the skin."

A 211-mile (340-kilometer) road was built from Port Blair, the capital city of the Andamans, through the heart of Jarawa territory, paving the way for mainlanders to settle on their land. Because the Jarawa are hunter-gatherers, they require lots of land. The road and increased population forced them deeper into the forest, where fewer resources are available.

A court ruling in 2002 was supposed to leave the Jarawa alone. The road has been closed, settlers requested to leave, and logging banned. But according to Mustafa, the damage is already done: "Jarawas now want our tobacco, alcohol, and biscuits, and we want their ornaments," he told me.

On Little Andaman Island, the traditional home of the Onge tribe, the first friendly contact with outsiders was made in 1885. Prior to that, nobody ventured on their land because of fear of getting killed. Sadly, today there are only 103 Onge left, down from 672 in 1901.

Do the islands still have a very primitive feel?In Port Blair the air was scented with wild orchids, and the shoreline is dotted with cute colored cottages surrounded by emerald waters.

Other areas are far more primitive. One of my most memorable experiences was on Little Andaman Island. It is secluded and inaccessible, located between the Duncan Passage and the Ten Degree Channel. As I stepped on the island it gave me a sense of how Marco Polo must have felt when he arrived here in the 13th century.

After climbing 216 sweaty steps in humid tropical air to the top of Richardson's Lighthouse, I was rewarded with the most amazing views of wild, desolate beaches, waves crashing on shore, seabirds diving for fish, and thick mangrove forests protecting the inland.

I also took a canoe trip from Dugong Creek, the main settlement of the Onge on Little Andaman, and floated through dense mangroves, and forests of badam and gurjan trees. Because of the rich diversity of this region, Nicobari pigeons, wild pigs, monitor lizards, tortoises, and crocodiles thrive there.

Amid Savant, chief conservator of forests, was with me and told me that the Onge had recently killed 13 crocodiles there, slitting the bellies open to look inside the stomach for the remains of a little infant girl who had been snatched away and eaten the day before. Savant told me that, according to Onge belief, the little girl must be found and her bones put to rest in a proper burial in the trees.

The Onge will kill as many crocodiles as it takes to find her, Savant said. He was concerned about the possible environmental consequences.

In addition to roads, disease, and incursions by mainlanders, what are some of the other threats to these tribes and their islands?In Ramakrishapur village, we met three Onge men who had canoed to the settlement to buy fishhooks and a knife for cutting branches in the forests. They are small - 4 feet (1.2 meters) tall - and muscular, with intensely dark eyes and skin and brilliant white teeth illuminating their faces. They told us about the deforestation of their land to make way for coconut plantations.

One result has been the loss of a valuable indigenous plant, a cure for high fever. The oldest man told me that now tribal members need to walk a full day to buy Western medicine. Ironically, the Onge tribe has a cure for the deadliest form of malaria, black-water malaria. Western pharmaceutical companies can't wait to get access to this plant.

Are there myths or legends that have been passed down through the generations that help the people explain this disaster?The spirit god Pulga is said to live on North Andaman Island, at the summit of Saddle Peak, at 2,418 feet (737 meters), the highest point of the archipelago. The Andamanese tribes fear him, because he punishes humans, causes storms, and "has a way with ancestors," according to Mustafa. In Andaman mythology, Pulga caused the cataclysmic flood that separated the Andamanese from their relatives on the mainland.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter