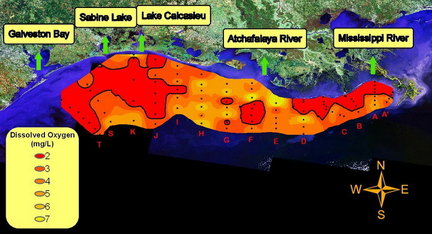

The annual summertime dead zone caused by low oxygen levels in water along the Gulf of Mexico shoreline this year is twice as big as last year's, stretching 7,722 square miles across Louisiana's coast well into Texan waters, scientists with the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium announced Monday.

But there's no evidence the larger expanse of low-oxygen water -- which covers an area as big as Massachusetts, and is linked to nutrients carried to the Gulf by the Mississippi River -- was made bigger by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, scientists said.

Last year, the area affected by low oxygen was limited by lower springtime water levels in the Mississippi River, which meant less nutrients reached coastal waters. Also, persistent winds from the west and southwest last year may have driven low-oxygen water out of the easternmost Louisiana waters where last year's mapping was done.

The size of this year's dead zone might actually be larger than mapped. LUMCON's RS Pelican research ship found a large area of hypoxia, or low-oxygen water, along the coast west of Galveston Bay and offshore in that area, but was unable to finish mapping there before returning to map an area east of the Atchafalaya River.

"This is the largest such area off the upper Texas coast that we have found since we began this work in 1985," said Nancy Rabalais, executive director of LUMCON and chief scientist for the dead-zone cruise.

The low-oxygen area is linked to high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, the main ingredients of agricultural fertilizers, and other nutrients carried by the Mississippi River from the Midwest into the Gulf. There, they feed springtime and summertime blooms of algae at the surface, which sink to the bottom and decompose when they die, using up oxygen in the water.

It's still unclear what effect, if any, the oil spill had on the size of this year's zone, Rabalais said.

"We only saw a little bit of oil during our cruise, the obvious streaks and mousse on the surface at the river delta," she said in an interview.

"It's a very difficult question to study, even if we knew exactly where the oil had been," Rabalais said. "For it to have an effect on oxygen content, it would have to cover an area for a long time, and being out there myself and seeing it, it comes and goes and is never in the same place long enough.

"What we don't know is how much we've got on the bottom," she said, "but our low oxygen values are no larger than in other summers.".

Rabalais said she accidentally surfaced into an oil slick while scuba diving in May during an earlier research cruise.

The dead-zone size estimated by cruise scientists matches predictions made earlier this year by LSU biologist Eugene Turner, who predicted a range of sizes averaging 7,776 square miles, based on measurements of the nutrients carried by the Mississippi this spring.

The large area was driven by high river conditions during much of the spring and summer, Rabalais said.

"We had four peak discharges this year, beginning in January," she said. "We're coming down from a peak discharge now, and are well above the average" flow of freshwater from the Mississippi into the Gulf. On Monday, the river was at 7.9 feet at New Orleans, while a year ago, it was at a more normal summer level of 4.4 feet.

Oxygen levels of less than 2 parts per million, which are considered hypoxia, can kill organisms in bottom sediment in the Gulf that are the source of food for other species, like shrimp and fish.

The size of the dead zone is an important benchmark that scientists hope to use to measure the effectiveness of a national effort to reduce the nutrients entering the Mississippi.

The Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force has a goal of reducing the average size of dead zones to 1,900 square miles by 2015. Plans call for doing that largely through voluntary efforts aimed at lowering farm fertilizer use, creating wetland and grassy areas on the edges of farmland, and asking industries, urban sewage systems and septic tank owners to reduce emissions.

A number of environmental organizations, scientists involved in tracking nutrient pollution, and even the federal Environmental Protection Agency's inspector general contend such voluntary efforts are not moving quickly enough, however.

"It is time for the states and federal agencies in the Dead Zone Taskforce to show some urgency for cleaning up the Mississippi River and the Gulf," said Matt Rota, water resources program director for the New Orleans-based Gulf Restoration Network. "We need to take the current 'In-Action Plan' and give it some teeth, with enforceable timelines and goals. Without these, we are just going to see the dead zone get worse."

Last August, the EPA Office of Inspector General recommended that the agency set numerical standards for the amount of nutrients allowed in the Mississippi and other water bodies, because state governments had been too slow to adopt their own measures.

"Critical national waters such as the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi River require standards that, once set, will affect multiple upstream states," the report said. "These states have not yet set nutrient standards for themselves; consequently it is EPA's responsibility to act."

This year's mapping found a patchwork of low-oxygen areas, rather than the usual continuous band of low oxygen along the coast, Rabalais said. That might be the result of mixing of oxygen-containing water on the surface with deeper water during Hurricane Alex, which crossed the southwestern Gulf in late June and early July, and Tropical Storm Bonnie two weeks ago.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter