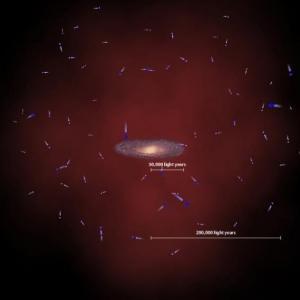

"The Galaxy is slimmer than we thought," said Xiangxiang Xue of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany and the National Astronomical Observatories of China, who led the international team of researchers. "We were quite surprised by this result," said Donald Schneider, a member of the research team, a Distinguished Professor of Astronomy at Penn State, and a leader in the SDSS-II organization. The researchers explained that it wasn't a Galactic diet that accounted for the galaxy's recent slimming, but a more accurate scale.

OF THE

TIMES