By unravelling the molecular identity of the relatively new blood type known as the Er system, a new study could hopefully prevent such tragedies in the future.

"This work demonstrates that even after all the research conducted to date, the simple red blood cell can still surprise us," says University of Bristol cell biologist Ash Toye.

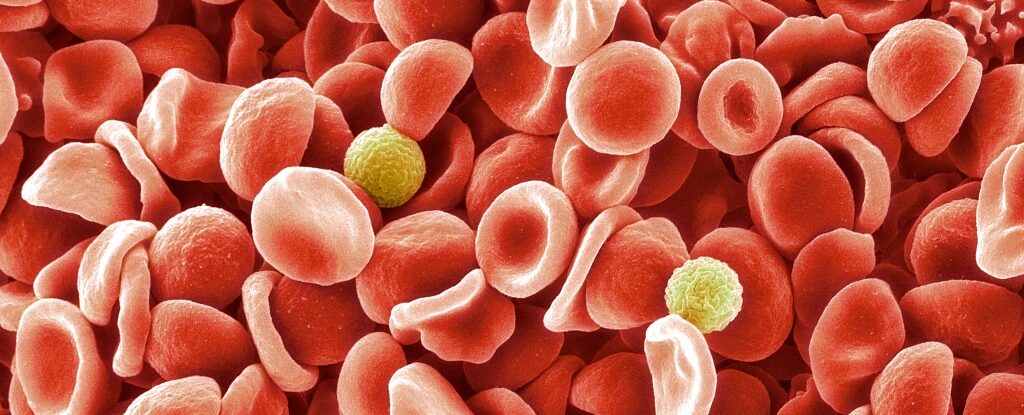

Blood typing describes the presence and absence of combinations of proteins and sugars that coat our red blood cells' surfaces. Though they can serve different purposes, our body generally uses these cell-surface antigens as identification markers with which to separate self from potentially harmful invaders.

We're most familiar with the ABO and rhesus factor (that's the plus or minus) blood group systems, thanks largely to their prime importance in matching blood transfusions. But there are actually many different blood group systems based around a wide variety of cell-surface antigens and their variants.

Most of the major ones were identified in the early 20th century, though a late-comer to the collection, called Er, only popped onto our radar in 1982, forming the foundation for a 44th blood group. Six years later, a version named Erb was identified. The code Er3 was used to describe the absence of Era and Erb.

While it's been clear for decades now that these blood cell antigens exist, too little has been known about their clinical impact.

When a blood cell shows up with an antigen that our body has not classified as one of our own, our immune system activates, sending out antibodies to flag the suspect-antigen-bearing cells for destruction. In some cases a mismatch between an unborn baby and their mother's blood type can cause problems if the mother's immune system become sensitized to foreign antigens. The antibodies generated in response can then pass through the placenta, leading to hemolytic disease in the unborn baby.

Luckily, there are several methods of preventing or even treating hemolytic disease in newborns these days, including injections for pregnant mothers and blood transfusions for the babies.

Sadly, for one of the cases mentioned in the study, a blood transfusion following a cesarean section delivery failed to save the child's life, suggesting there was something doctors - and researchers - were missing.

"We work on rare cases," serologist Nicole Thornton from the UK's National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) told Wired. "It starts off with a patient with a problem that we're trying to resolve."

Hints of these rare antibodies have shown up over the years, but their rareness made our understanding of them elusive until now.

So Thornton and colleagues led by NHSBT serologist Vanja Karamatic Crew, analyzed the blood of 13 patients with the suspect antigens. They identified five variations in the Er antigens: the known variants Era, Erb, Er3, and two new ones Er4 and Er5.

Sequencing the genetic codes of the patients, Crew and team were able to pinpoint the gene that codes for the cell surface proteins. Surprisingly it was a gene already familiar to medical science: PIEZO1.

"Piezo proteins are mechanosensory proteins that are used by the red cell to sense when it's being squeezed," explains Toye.

The gene is already associated with several known diseases. Mice without this gene die before birth and those that have the gene deleted in just their red blood cells end up with overhydrated and fragile blood cells.

Crew and team confirmed their findings by deleting PIEZO1 in a cell line of erythroblasts, a precursor to red blood cells, and testing for the antigens. Sure enough, PIEZO1 is required for the Er antigen to be added to the cell's surface.

As they found a high prevalence of an Er5 variant in African populations, the researchers suspect this variant may convey some sort of advantage against malaria, like some other rare blood types found there.

"The protein is present at only a few hundred copies in the membrane of each cell," explains Toye. "This study really highlights the potential antigenicity of even very lowly expressed proteins and their relevance for transfusion medicine."

Their research was published in Blood.

Why did you kill that children in the first place ?

S ome public statements (gaffes, actually) stick. Like that one :" We own the science ".