BOOK REVIEW: Digging up Armageddon: The Search for the Lost City of Solomon Eric H. Cline Princeton Univ. Press (2020)"Welcome to Armageddon," say Israeli tour guides, as groups from many countries climb the steep incline of the archaeological mound Tel Megiddo, southeast of Haifa and close to Nazareth. Within it are the remains of at least 20 cities, piled up, dating from about 5000 bc to the fourth century bc. Passing through the current gate, the tourists often burst into hymns or prayer.

"Our small group of archaeologists smile tolerantly," recalls Eric Cline in Digging Up Armageddon. They have been digging since before dawn to avoid the heat. A chain-link fence around the excavations jokingly requests: "Please do not feed the archaeologists."

Thus opens an original and lively study that skilfully mixes archaeology with personalities, and politics with culture, science and technology — such as the pioneering 1929 use of a crewless hydrogen balloon to photograph an archaeological site from the air. Dry and detailed analysis of strata and objects mingles with heroic archival excavation of biographical information, personal anecdotes and interpersonal struggles, beginning with the first dig, in 1903-05. The whole benefits from Cline's personal experience. Over ten seasons from 1994 to 2014, starting as a volunteer, he dug in most areas opened up by a Tel Aviv University expedition, rising through the ranks to become co-director with Israel Finkelstein.

The book, however, focuses firmly on 1925-39, the most revealing period of excavations. These were run by the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, Illinois, under its inaugural director, Egyptologist James Henry Breasted, who coined the phrase 'Fertile Crescent'. Funded by business magnate John D. Rockefeller, the digs were set against the troubled political background of the British Mandate for Palestine, a territory established after the defeat of the forces of the Ottoman Empire at the Battle of Megiddo in 1918. Excavations ceased in 1939, when many team members enlisted in the armed forces, "trying to stop the modern world from heading down the road toward a new Armageddon". In 1948, the year Israel was founded, the expedition's dig house was looted and accidentally burnt down.

Breasted and Rockefeller were fired up by the legend of Armageddon in the Bible, which originally refers to the place as Megiddo, supposedly built by King Solomon in the mid-tenth century bc. Solomon is recorded only in scripture, but Megiddo is mentioned in many other ancient texts, such as the records of Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III, whose armies captured the city in 1479 bc. 'Armageddon' derives from Hebrew Har Megiddo, meaning the mound or mountain of Megiddo. By medieval times, having passed through multiple languages, these two words had transformed into Harmageddon and thence Armageddon. In the New Testament's Book of Revelation, Armageddon witnesses the ultimate battle between the forces of good and evil before the Day of Judgement — hence its modern use as a byword for the end of the world.

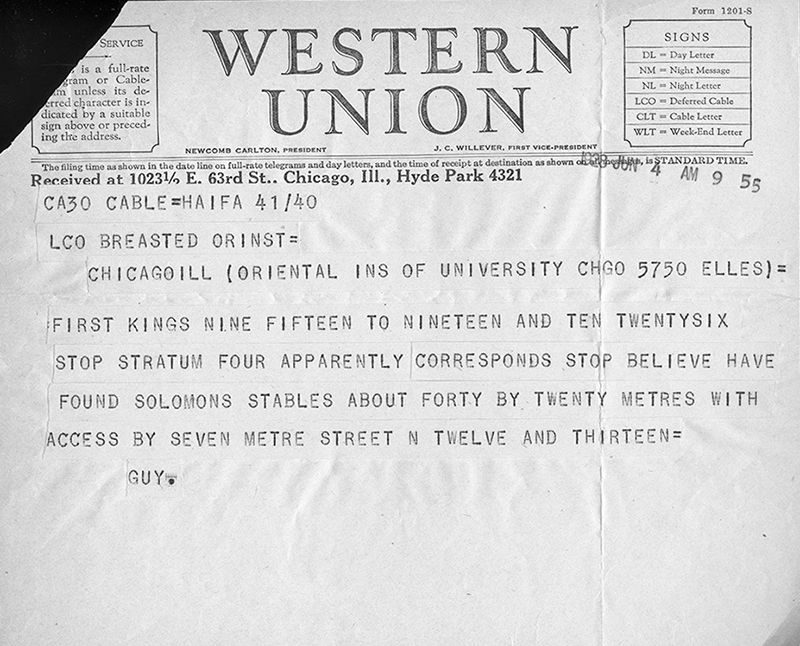

Thus the excitement in 1928, when the expedition's field director cabled Breasted in Chicago: "BELIEVE HAVE FOUND SOLOMONS STABLES". As evidence, the telegram cited the Old Testament, which states that Solomon had 1,400 chariots and 12,000 horsemen stationed in "chariot cities" Hazor, Megiddo and Gezer, and in Jerusalem. The New York Times ran an article that launched Megiddo into "the limelight of biblical archaeology, where it has remained ever since", notes Cline.

Unexplained cataclysm

Another contentious issue arose from an older stratum that revealed fire-blackening and crushed skeletons, including that of a young girl lying where she had been hit by a falling wall. But what devastated Megiddo in this period? One 1930s excavator postulated a "violent siege and fire by the incoming Philistines, probably circa 1190 bc". The existence of the Philistines is attested by archaeological evidence elsewhere. However, no arrowheads or other weapons were found in or near the Megiddo bodies; nor were there sword marks on the skeletons. In addition, the walls had been misaligned by forces greater than could have been exerted by humans, even humans with battering rams. Moreover, the layer belongs to the tenth century bc, according to twenty-first-century radiocarbon dating.

Cline and others suggest that there was a major earthquake. These certainly occur in the eastern Mediterranean — for example, at Jericho in 31 bc and ad 1927 — as Cline explored in his 2014 book 1177 bc: The Year Civilization Collapsed. However, ancient earthquakes are notoriously hard to authenticate without a contemporary written record. The only certainty, writes Cline, is that the destruction "was an Armageddon for the inhabitants, regardless of whoever or whatever caused it".

Megiddo was finally abandoned just before 300 bc. At least one scholar has proposed that Alexander the Great destroyed the city, "but there is no evidence for such a cinematic finale", jokes Cline — despite the site's long military history. It's more likely that Alexander's army marched past the towering unoccupied mound, unaware of its already historic significance.

Nature 578, 510-511 (2020)

doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00510-w

Comment: See also: