A team of Italian researchers have strengthened the case that at least the cranium found near Pompeii 100 years ago really does belong to Pliny the Elder, a Roman military leader and polymath who perished while leading a rescue mission following the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 C.E. However, a jawbone that had been found with the skull evidently belonged to somebody else.

Over the last couple of years the experts, including anthropologists and geneticists, conducted a host of scientific tests on the skull and lower mandible that had been found a century ago on the shore near Pompeii, which have since been at the center of a scholarly debate as to whether they should be attributed to Pliny.

The main finding of the researchers, who presented their conclusions at a conference in Rome on Thursday, is that the jawbone belonged to a different person, but that the skull is compatible with what we know about Pliny at his death.

"This is the first scientific study of the supposed remains of Pliny the Elder, and the clues that have emerged increase the likelihood that it is him," says Andrea Cionci, an art historian and journalist who first reported the findings in Italy's La Stampa newspaper.

Fatal curiosity

This would mark the first positive identification of the remains of a high-ranking figure from ancient Rome, highlighting the work of a man who lost his life while leading history's first large-scale rescue operation, and who also wrote one of the world's earliest encyclopedias.

Gaius Plinius Secundus, better known as Pliny the Elder, was the admiral of the Roman imperial fleet moored at Misenum, north of Naples, on the day when Vesuvius erupted.

According to his nephew, Pliny the Younger, an author and lawyer in his own right who also witnessed the eruption from Misenum, Pliny the Elder's scientific curiosity was piqued by the dark, menacing clouds billowing from the volcano.

Pliny the Younger's account of the events of those days is considered very accurate, so much so that scientists have dubbed the type of explosive volcanic eruption he described a "Plinian eruption."

In a letter to the Roman historian Tacitus, the younger Pliny recounts that his uncle ordered his fleet to set sail for the Vesuvius area, both to investigate the phenomenon and to help "the many people who lived on that beautiful coast."

According to Pliny the Younger, the fleet and its commander disembarked at Stabiae, a town on the shore near Pompeii. But as he was leading a group of survivors to safety, Pliny the Elder was overtaken by a cloud of poisonous gas, and suffocated to death on the beach at age 56.

Bodies are found

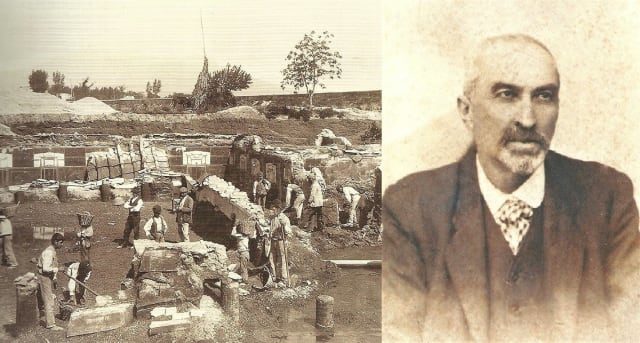

In the first years of the 20th century, amid a flurry of digs to uncover Pompeii and other sites preserved by the layers of volcanic ash that covered them, an engineer called Gennaro Matrone uncovered around 70 skeletons near the coast at Stabiae.

One of the bodies bore a golden triple necklace chain, golden bracelets and a short sword decorated with ivory and seashells.

The engineer-cum-archaeologist was quick to theorize that the sword, the precious jewels and their sea-related iconography marked the remains as those of a naval commander like Pliny. Indeed, the place and the circumstances were right, but other scholars at the time laughed off the hypothesis.

Humiliated, Matrone sold off the jewels to unknown buyers (laws on conservation of archaeological treasures were more lax then) and reburied most of the bones, keeping only the supposed skull and jawbone of Pliny as well as his sword, Russo said.

These artifacts were later donated to a small museum in Rome - the Museo di Storia dell'Arte Sanitaria (the Museum of the History of the Art of Medicine) - where they have been kept, mostly forgotten, until recently.

In 2014, Flavio Russo, an engineer and military historian, published a book for Italy's Chief of Staff about Pliny's rescue mission and picked up Matrone's initial theory on the remains. Russo has since been putting together funding from private sponsors and a team of experts to test the bones.

The initial tests were encouraging, says a news release that the team circulated ahead of Thursday's conference. The enamel in our teeth contains isotopes that can be traced to the region in which we grew up.

Knowing that Pliny was born and bred in what is today the northern Italian town of Como, the scientists conducted an analysis of the teeth in the jawbone to see if the data would match. And indeed, they found that those teeth belonged to someone who had spent their infancy in northern Italy, the release says.

Then the investigation hit a big snag. Roberto Cameriere, a forensic anthropologist from the University of Macerata, concluded that the teeth belonged to a person aged around 37, way too young to be Pliny the Elder.

"Damn, we thought, so it's not him," Cionci recalls.

Pliny and his slave?

Then, another anthropologist suggested that the jawbone and the skull may have belonged to two different people. DNA tests confirmed this hypothesis: the jawbone came from a man whose ancestry could be traced to North Africa. But the skull's haplogroup was typical of Italic populations in the Roman period, which would still make it possible to identify it as Pliny's.

So, it seems that in the jumble of skeletons found on the beach in Stabiae, the archaeologists mistakenly associated the skull and jawbone of two different people.

Russo, the military historian, says the isotope analysis and the DNA tests suggest the owner of the jawbone was likely a second-generation African who grew up in northern Italy. He may have been a sailor, as a large part of ancient Rome's mariners were recruited in North Africa, or he may have been a slave who grew up on the family's estate and served as Pliny's bodyguard.

So perhaps we have found the remains of one of the slaves who died along with the Roman admiral and the group of people they were trying to rescue.

But what about the skull? Is there any further information that can clear up the mystery of the bejeweled skeleton found by Matrone on the beach of Stabiae? An analysis of the sutures in the skull bones does indicate that the individual was of the right age, says physical anthropologist Luciano Fattore.

Human babies are born with open cranial sutures to allow the brain to grown and which progressively seal up as we age. Anthropologists can give a range for the age-at-death of an individual judging by the state of the cranial sutures. However, Fattore cautions, that range becomes wider and less precise the older the person is.

In the case of the putative Pliny skull, the sutures on the top of the skull showed an age of 45 years, plus or minus 12 years. The sutures on the sides of the skull were typical of someone aged 56, plus or minus eight years.

"On average, these numbers are compatible with the possibility that the skull belonged to Pliny," Fattore tells Haaretz.

So, to sum up this century-old forensic mystery: we have a skull of a high-ranking Roman official who died at the time, place and circumstances in which ancient sources say this occurred; his DNA and skull are compatible with the age and ancestry of the 'hero of Pompeii.' But is this enough to say that we have found Pliny's remains?

"We can never be completely certain," Cionci says. "But so far none of our findings have contradicted this theory, and if anything, the evidence in favor of it just keeps mounting."

I have no doubt Pliny ever existed.

I'm no biggot and science-denier, I believe everything scientists say.