A new forensic technique sailed through its first test in court, leading to a guilty verdict. But beyond the courtroom, a battle over privacy is intensifying.

It has been used to identify more than 40 murder and rape suspects in cases as much as a half-century old. It has led to guilty pleas and confessions, including in one case where another man was convicted of the crime.

Genetic genealogy — in which DNA samples are used to find relatives of suspects, and eventually the suspects themselves — has redefined the cutting edge of forensic science, solving the type of cases that haunt detectives most: the killing of a schoolteacher 27 years ago, an assault on a 71-year-old church organ player, the rape and murder of dozens of California residents by a man who became known as the Golden State Killer.

But until a trial this month in the 1987 murder of a young Canadian couple, it had never been tested in court. Whether genetic genealogy would hold up was one of the few remaining questions for police departments and prosecutors still weighing its use, even as others have rushed to apply it. On Friday, the jury returned a guilty verdict.

"There is no stopping genetic genealogy now," said CeCe Moore, a genetic genealogist whose work led to the arrest in the murder case. "I think it will become a regular, accepted part of law enforcement investigations."

Detective James H. Scharf of the Snohomish County Sheriff's Office in Washington State took all of six minutes on the stand to describe how a semen sample collected from the clothing of one of the victims led to two second cousins of the suspect, and then to the name of the man on trial, William Talbott II.

The defense could have challenged the use of genetic genealogy on privacy grounds, or as a violation of people's right to control their personal data. Instead, defense lawyers did not pose a single question about the technique. After more than two days of deliberation, the jury convicted Mr. Talbott on two counts of murder.

Mr. Talbott's lawyers said they viewed genetic genealogy as just another way of generating investigative leads. "Police have always used a variety of things to develop tips," said Rachel Forde, a public defender, in an interview. The brother of one of the victims had even consulted a psychic at one point, she said.

But if the case quelled some investigators' concerns, it was not likely to put to rest a raging debate over the ethics of using the technique to solve crimes and how to balance privacy with the demands of law enforcement.

Just during the time Mr. Talbott spent awaiting trial, genealogy databases have changed their rules about cooperating in criminal investigations, and then changed them again. Cordial forums for genealogists have erupted into vicious battlefields. And the technique, once reserved for rape and murder cases gone vexingly cold, has been applied in less serious, more recent crimes, raising alarm among privacy advocates and long-time users of family history databases.

"We're currently in a state of flux," said Blaine Bettinger, a genetic genealogist and lawyer. "There is no guidance from any direction."

30 Years Without a Name

In 1987, 17-year-old Tanya Van Cuylenborg of Victoria, British Columbia, left for what was supposed to be a quick trip with her boyfriend, Jay Cook, 20.

When they did not return the next day, the Van Cuylenborg family became alarmed. "It was out of character," said John Van Cuylenborg, Tanya's older brother. "She wasn't a wild child."

His sister's body was found, partly clothed, in the woods. She had been shot.

Two days later, Mr. Cook's body was found 75 miles away. He had been strangled, with a pack of Camel Lights stuffed in his mouth. Their van was found in a third location. But the police had few leads.

By 1994, DNA testing had advanced to the point that semen found on Tanya's pants could produce a profile. In 2003, Individual A, as he was called, was uploaded to Codis, the FBI's criminal DNA database.

As the database grew, investigators hoped for a match, in vain. And then in 2017, Detective Scharf heard that there was a way to get more from DNA.

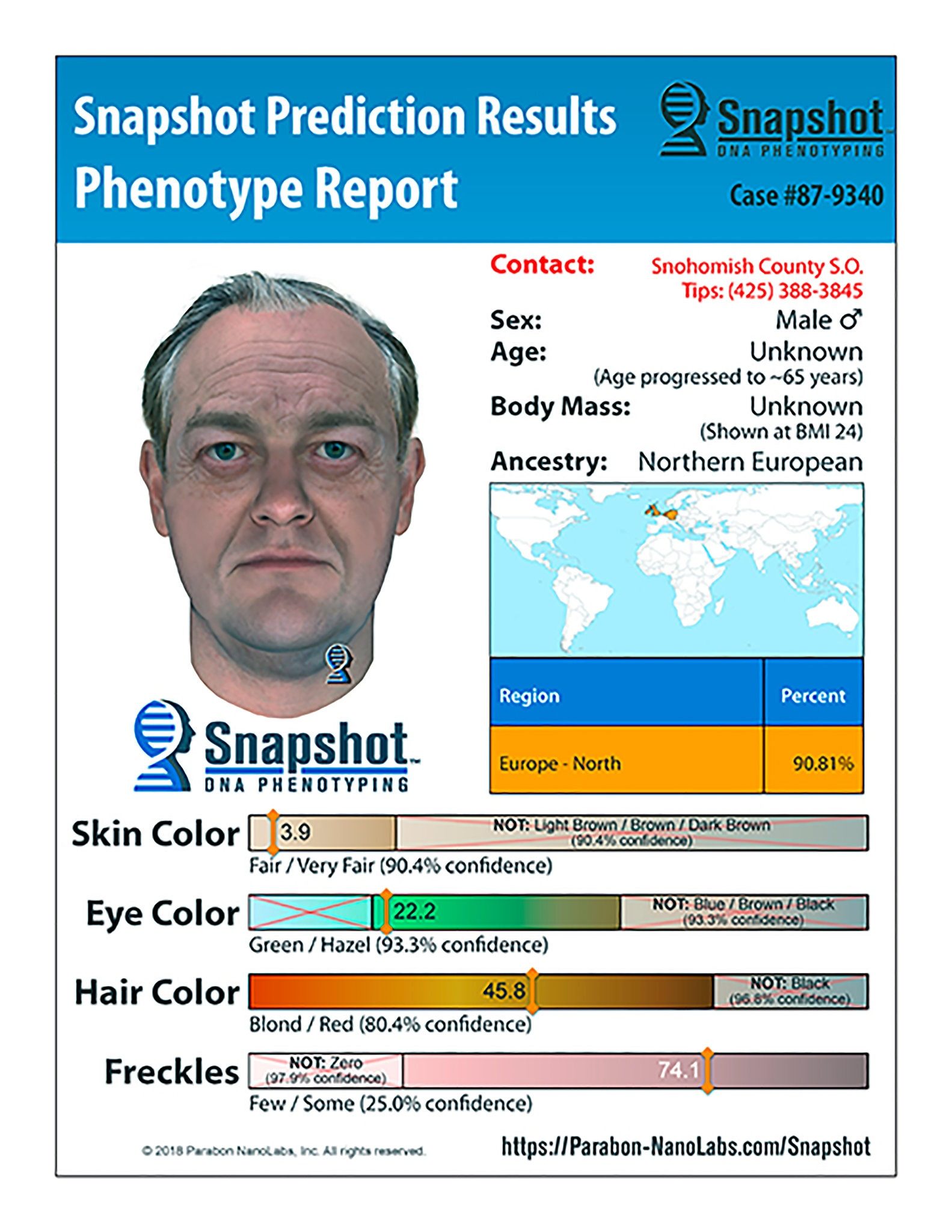

He collaborated with a genealogist to produce a list of possible surnames. None were correct. A forensic consulting firm, Parabon, offered to generate a predictive likeness using DNA. This was not helpful either.

"This is a case I've been working on so hard for so long that I never thought it would ever be solved," Detective Scharf said in an interview.

Finally, he learned of a new technique.

Science fiction writers had long predicted a government database that would contain the DNA of every citizen. But it took genealogists to realize that a version of that already exists, in the form of websites that allow people to upload their DNA profiles in order to find relatives. Using those profiles, many Americans — in particular, most white Americans — can be identified through their family tree.

Parabon offered to help. Detective Scharf, who had been working on the case for more than a decade, was skeptical when the company said that it would have results by the end of the week.

But the call came just a few days later. "He told me we had a match," Detective Scharf said on the witness stand, starting to choke up when he uttered the name: "William Earl Talbott II."

Who is Mr. Talbott?

Throughout the trial, Mr. Talbott, a solemn man with a gray beard, sat silently between his lawyers. One afternoon, he attempted a smile.

Mr. Talbott is a longtime truck driver who likes to camp. Letters submitted to the court by friends describe him as a kind man who they believe to be incapable of violence. At 56, he had never before been convicted of a crime.

Nor had he ever joined a genealogy site. But two of his second cousins, one on his paternal side and one on his maternal side, had.

Ms. Moore, the lead genetic genealogist for Parabon, used newspaper archives and marriage records to build a family tree back to the two cousins'great-grandparents — and then forward to a particular couple who lived about seven miles from where Mr. Cook's body was found.

Ms. Moore homed in on their only son, who would have been 24 at the time of the murders.

Next, an undercover officer who was watching Mr. Talbott collected a cup that fell off his truck. Once in custody, Mr. Talbott also provided a cheek swab. Both matched Individual A.

His lawyers did not dispute the match. They have instead fought the idea that the presence of his semen meant that he killed someone.

"1994 is when the DNA profile was developed and from there nothing else mattered; it was complete tunnel vision," Ms. Forde said in her closing statement on Tuesday. She emphasized that there was no DNA connecting her client to the scene of Mr. Cook's murder.

Detective Scharf said that years investigating crimes against children had made him doubt any claim that someone is not "the type" to be a perpetrator.

"Everyone in this world has secrets," he said.

The Battle

Long before an arrest in the Golden State Killer case in April 2018 made genetic genealogy famous, a small group of experts knew that identifying suspects in criminal cases was possible. But they were divided over whether it was ethically acceptable.

The group — some call them the "genealogy influencers" — debated the issues on blogs and in private forums. Each member has a claim to fame: the first to help an adoptee find her biological mother, the first to identify a body, the first to find a killer's full name.

One school of thought holds that if users join an easily searchable site, they should not expect to maintain control over how their information is used, and that criminal investigations serve the greater good. Another says that people deserve to be able to make informed decisions about how their DNA — the most personal of personal information — is used.

Both the Golden State Killer's profile and Individual A's had been uploaded to a large genealogy site called GEDmatch at a time when such sites had not explicitly told users that their profiles could be used to solve crimes.

Though some of the influencers objected, the public response to the resulting arrests was enthusiastic. GEDmatch changed its user agreement to allow for law enforcement use in rape and murder cases.

Mr. Talbott's lawyers did not challenge the timing of the upload or the prosecution's decision to call GEDmatch a "public database."

But beyond the beige walls of the Snohomish County Superior Court, the arguments continued.

Curtis Rogers, the owner of GEDmatch, got a call from a detective after a 71-year-old woman was attacked while playing a church organ in Utah. It sounded to Mr. Rogers, he said in an interview, like an "attempted murder," and he allowed the site to be searched. A 17-year-old high school student was arrested.

Critics said the search was a violation of the user agreement because the case did not involve rape or murder. "GEDmatch can no longer be trusted," wrote Judy Russell, who blogs under the name The Legal Genealogist.

GEDmatch responded by changing its terms of service yet again, expanding the list of crimes, but allowing searches only of those users who explicitly opted in.

In Texas, another GEDmatch search occurred after the police said they were looking for a sexual predator. But when a genetic genealogist gave the police a name, they charged him with burglary, raising questions yet again about whether the user agreement had been violated.

Another legal wrinkle involves the question of who is injured when the police conduct a database search. In Mr. Talbott's case, several lawyers said, traditional legal thinking would hold that the cousins' privacy was violated, not his.

Leah Larkin, who runs The DNA Geek, a company that helps people track down relatives, said that when the police argue that genetic genealogy is like any other tip system, they disregard the vast troves of personal information contained within a single genetic file, such as whether a suspect was born out of wedlock, was the product of incest, or carries genetic diseases.

In many states — including Washington — the police are prohibited from using Codis, the criminal DNA database, to search for relatives.

"It's a 'tip system' that even convicted criminals can't be forced to participate in," Dr.. Larkin said. "Yet is being used on innocent people without their knowledge or consent."

Heather Murphy is a science reporter. She writes about the intersection of technology and our genes and how bio-tech innovations affect the way we live. @heathertal

I think solving cold cases is good...but this is just wrong, and chilling in a 1984'ish sort of way....