Many people think of mental health problems like depression, anxiety, and ADHD as chemical imbalances that require medication, but how often do we stop to wonder what causes these chemical imbalances? While medications are clearly helpful and important for some individuals, one could argue that the most powerful way to change brain chemistry is through food - because that's where brain chemicals come from in the first place.

This logical idea has given birth to the new and exciting field of nutritional psychiatry, dedicated to understanding how dietary choices affect our mood, thinking, and behavior. Emerging science and real-world experiences are revealing this empowering and hopeful new message: feeding your brain properly has the potential to prevent and reverse symptoms of mental health disorders, and in some cases, help people reduce or even eliminate the need for psychiatric medications.

The steep rise in mental health problems around the world in recent decades closely parallels the pattern of many other so-called "diseases of civilization" associated with the industrialization of the human diet.2 Although many public health messages blame animal protein and fat for our predicament, meat is not a risky new foreign substance; it is an ancient, highly nutritious whole food that has been available since time immemorial.3

While we can't know precisely how much meat pre-historic peoples around the world used to eat, we do know that no human being could have survived without animal foods, because plant foods lack certain nutrients essential to human life, most notably vitamin B12, and B12 supplements were not available prior to the 1950s.4

What best distinguishes today's so-called "Western" diet from every dietary pattern that has ever come before it is not the presence of meat, but the abundance of refined carbohydrates like sugar and flour, and refined seed oils (aka "vegetable oils") such as soybean and sunflower oil. These two substances, which are found in nearly every processed and prepared food on the market, are the true signature ingredients of modern diets.

Refined carbohydrates and seed oils may endanger physical and mental health by contributing to inflammation, oxidation, hormonal imbalance, and insulin resistance - all of which science suggests may be key drivers of many physical and mental health problems. (A guide to how sugar and processed food may damage the brain is coming soon.)

To be clear, these are not the only forces at play, and poor dietary quality is not the only factor influencing our risk for psychiatric disorders. However, since there is solid science connecting food choices with disease-producing processes, improving the quality of our diet makes good sense.

Low-carbohydrate diets and psychiatric disorders

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder (excessive worry), panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and social phobia. While there aren't any formal published studies yet, there are numerous anecdotal reports and examples within my practice of people achieving significant relief from anxiety on LCHF and ketogenic diets.5 In my clinical experience, anxiety reduction is one of the most common benefits of LCHF diets, perhaps because they lower and stabilize stress hormone levels.

A 31-year-old Mexican-American Harvard post-doctoral student came to me requesting help with frequent panic attacks, irritability, constant food cravings, "emotional eating", and sleepiness occurring two hours after meals. She was very health-conscious and hoped to avoid medication. I told her that her symptoms were probably related to carbohydrate sensitivity and recommended a whole foods LCHF diet. She changed her diet from this:

- Breakfast: Toast with peanut butter or Nutella, coffee with skim milk

- Lunch: Salad with tuna or cheese and a piece of bread

- Dinner: Pasta with cheese

- Snacks: Bananas and yogurt

- Breakfast: Two eggs with butter and guacamole

- Lunch: Meat and non-starchy vegetable

- Dinner: Meat and non-starchy vegetable

- Snacks: Nuts and cheese

Depression

Medicines which reduce inflammation and improve insulin resistance can effectively treat depression symptoms, suggesting that inflammation and insulin resistance may play an important role in the development or severity of depressive disorders.6

In 2017, the world's first study of dietary intervention for clinical depression found that a Mediterranean-style diet eased depression symptoms to a modest degree as compared to the typical modern diet, and a second study of a similar diet supplemented with fish oil noted benefits as well.7

These important studies clearly demonstrate that dietary quality matters to mental health, but they can't tell us whether a Mediterranean diet is the best diet for the brain, only that it's better than the standard modern diet. While it is tempting to believe that these diets lessened depression symptoms because they are higher in foods like olive oil and nuts, they were also designed to be very low in refined carbohydrates and seed oils. More studies are needed to explore how and why different diets affect depression symptoms.

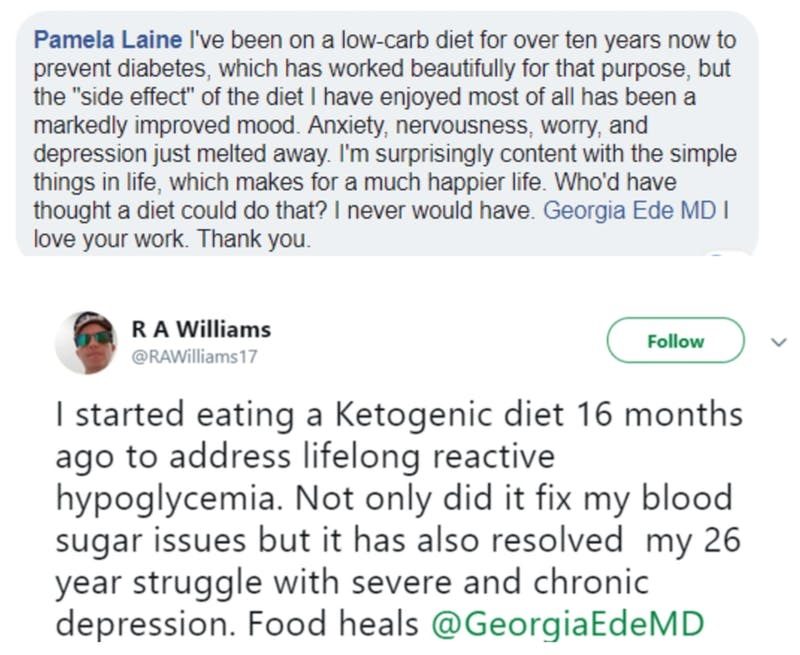

There is no published human science yet on low-carbohydrate diets and depression, but there are numerous instances within my own practice and many shared anecdotes of people reporting improved mood, including these two social media reports, shared with permission:8

Bipolar disorders

This condition used to be called "manic-depression" and comes in many forms, including bipolar type 1, bipolar type 2, and some common milder forms that don't fit neatly into either category. All of these disorders are characterized by unstable mood patterns that include periods of increased intensity ("highs") such as mania, irritability, or severe anxiety, usually alternating with periods of depression. Interestingly, bipolar disorder and epilepsy have a lot in common, including similar neurotransmitter imbalances and electrolyte disturbances.9

In fact, since some of the same medications are used to treat both disorders, it's logical to wonder whether ketogenic diets, which have been used to treat epilepsy for nearly a century, could be helpful in managing bipolar disorder as well.

- A study of 121 people with bipolar mood disorders found that those who also have insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes face a harder road than those who don't. Although this study finds strong odds ratios well exceeding 2.0, this is a single observational, cross-sectional study, therefore the strength of evidence is very weak.10 Those with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes were more likely to have chronic and rapidly-cycling mood symptoms and were less likely to respond to the mood-stabilizing medication lithium.

- In this published case study, two women with bipolar 2 disorder reported that a ketogenic diet was superior to the anticonvulsant/mood stabilizer lamotrigine (Lamictal) for managing their mood symptoms and were able to stop taking medication.11

- In an example from my own practice, a 26-year-old woman with bipolar 2 disorder who had struggled with bulimia and frequent migraines for many years adopted an LCHF diet and experienced complete resolution of binge-purge behaviors, migraines, and premenstrual distress.12 In addition, her "highs" shifted from angry to happy and her "lows" became less intense. We managed the leftover depression symptoms with a low dose of lamotrigine (a mood-stabilizing antidepressant medication) and psychotherapy.

Psychotic symptoms don't just occur in people with schizophrenia; they can also occur in many other psychiatric conditions, including depression, bipolar disorder, substance use disorders and dementia.

Signs of psychosis include paranoia, auditory hallucinations (hearing voices), visual hallucinations (seeing things that aren't there), intrusive thoughts/images, and/or disorganized thinking. Interestingly, people diagnosed with schizophrenia are more likely to have glucose regulation problems and insulin resistance, even if they've never taken antipsychotic medications known to increase risk for these issues.13

We don't have enough information yet to know whether insulin resistance may play a causal role in schizophrenia, only that the two conditions often go hand-in-hand.

Several published reports have documented that low-carbohydrate diets can dramatically improve symptoms of psychosis.14 Perhaps the most remarkable and best-documented case, published by Dr. Eric Westman and Dr. Bryan Kraft, tells the story of a 70-year old woman who had suffered with auditory and visual hallucinations since age seven. Within only eight days of switching to a low-carbohydrate diet, her symptoms noticeably improved. She remained free of hallucinations while eating this way even a full year later. You can read more details about some of these cases in this article: "Ketogenic diets for psychiatric disorders: a new 2017 review."

Autistic spectrum disorder (ASD)

Two small six-month studies and one case report have demonstrated that a ketogenic diet may be helpful with symptoms of autistic spectrum disorders in children.15 In one of the studies, of the 23 children who stuck with the diet, 18 children (60%) experienced some degree of benefit, with two children improving enough to advance to mainstream schools.

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

While there are studies suggesting that simplified low-allergen diets consisting primarily of whole foods can be very helpful in children with ADHD, there are no studies yet that explore the relationship between refined carbohydrates and ADHD or that test low-carbohydrate diets on children or adults with ADHD.16 However, in my clinical experience, improved mental clarity is one of the most commonly reported benefits of low-carbohydrate diets, and I have seen cases of even severe ADHD that have responded to dietary intervention, such as this one:17

Several years ago, I met with a 40-year-old woman who'd had lifelong symptoms of procrastination, lateness, poor motivation, low energy, distractibility, and disorganization that interfered significantly with her effectiveness at work and at home. I diagnosed her with ADHD, inattentive type, and she was started on Adderall (mixed amphetamine salts). Adderall helped greatly with her symptoms but brought uneven benefits throughout the day and some annoying side effects. Over the past couple of years, she gradually improved the quality of her diet by removing grains, legumes, dairy, and most processed foods, which helped her mood and improved her physical health tremendously, but did nothing for the ADHD symptoms. When she decided to shift to a ketogenic diet several months ago, her symptoms began improving within just a few days. She has since stopped Adderall entirely and reports that she functions even better when in ketosis than on Adderall, without any side effects.

Alzheimer's disease

Research exploring the connection between metabolism and most psychiatric disorders is in its infancy, but when it comes to Alzheimer's disease, we have multiple lines of mature, high-quality evidence firmly establishing that insulin resistance of the brain is not only a core feature of Alzheimer's disease, but is likely to be a primary driving force in the development of this devastating illness. The relationship between insulin resistance and Alzheimer's is so strong that many scientists now refer to Alzheimer's as "type 3 diabetes."18

One of the ways insulin resistance contributes to poor brain function in Alzheimer's disease is by restricting insulin's entry into the brain, as described in our guide to how sugar and processed food may damage the brain, which is coming soon. Since insulin is required for brain cells to turn glucose into energy, low brain insulin can cause sluggish brain glucose processing and slowing of brain cell activity. This drop in brain power can begin decades before any cognitive symptoms become obvious and has been detected in women as young as 24 years old.19 So, it's never too early to begin reducing your risk.

It's also almost never too late. A small but growing number of studies demonstrate that mildly ketogenic diets and/or ketone supplements modestly improve thinking and memory in some people with "mild cognitive impairment" (pre-Alzheimer's).20 Even for those in early, milder stages of Alzheimer's disease. In the 2018 study described here, the LCHF diet plus MCT oil supplements (which raise blood ketone levels) improved cognitive test scores in people with mild Alzheimer's disease a little better than any existing Alzheimer's medication.

This dietary strategy was safe, well-tolerated and manageable with the help of a caregiver.

Eating disorders

Thus far, there haven't been any published studies of low-carbohydrate diets for eating disorders. However, in my clinical practice, people with binge eating and bulimia who try a low-carbohydrate diet often experience relief from binge behaviors, because their cravings usually diminish significantly.21 Since binge eating triggers the impulse to purge, LCHF can be a very helpful strategy for people with bulimia who are willing to change their diet. Dairy and/or nuts can also trigger urges to binge in some people, so sometimes those foods need to be eliminated as well for best results.22

However, if you have a history of undereating or have ever had anorexia, anorexic thought patterns, or are uncomfortable with eating fat, a low-carbohydrate diet may not be right for you. When you dramatically reduce carbohydrate, you must replace those calories with calories from healthy fats. If you can't increase your fat consumption substantially, a low-carbohydrate diet could be deadly, especially if you are already underweight or malnourished. If you are considering a low-carbohydrate diet, please seek medical and psychiatric consultation to discuss the risks and benefits as they pertain to your personal history and goals.

Summary

Although the food-mood link is still an emerging field of study, there is great potential for many to unlock better mental health by modifying our modern diets and giving up processed food.

But how do you begin a low-carb diet? And how might psychiatric medications be affected? Please see our guide (coming very soon!) about easing into a low-carb diet if you are taking medication for mental health issues.

Also coming soon, our FAQ: Answers to common questions about low-carbohydrate diets for mental health!

/ Dr. Georgia Ede, MD

Notes

1. Psychosomatic Medicine 2019: The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [Meta-analysis of RCTs; moderate evidence]

Frontiers in Psychiatry 2017: The current status of the ketogenic diet in psychiatry [narrative review of mechanisms, animal studies and case reports; [ungraded]

Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2018: Ketogenic diet as a metabolic therapy for mood disorders: evidence and developments [narrative review of multiple lines of evidence; ungraded]

2. This is a review of observational studies exploring a possible connection between modernization and increased rates of mental illness. The strength of association reported in the individual studies cited within the review ranges from inconclusive to very weak.

Journal of Affective Disorders 2013: Depression as a disease of modernity: explanations for increasing prevalence [very weak evidence]

3. This is a review of the anthropological evidence suggesting that at least some pre-historic people were hunters and ate meat based on examination of fossil records. There is no way to test this hypothesis.

Meat Science 2018: A brief history of meat in the human diet and current health implications [weak evidence]

4. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2007: Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailability [strong evidence]

Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2012: The discovery of vitamin B(12) [historical review; strong evidence]

5. [anecdotal reports; very weak evidence]

6. Pharmacopsychiatry 2017: PPAR-γ agonists for the treatment of major depression: a review [moderate evidence]

7. Both studies were RCTs that added Mediterranean-style diets to existing conventional treatments (medications and/or therapy).

BMC Medicine 2017: A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the 'SMILES' trial) [moderate evidence]

Nutrition Neuroscience 2017: A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: a randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED) [moderate evidence]

8. [anecdotal reports; very weak evidence]

9. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 2010: Epilepsy and bipolar disorders [reviews multiple lines of evidence; ungraded]

10. Bipolar Disorders 2015: Insulin resistance in bipolar disorder: relevance to routine clinical care [very weak evidence]

11. Neurocase 2013: The ketogenic diet for type II bipolar disorder [very weak evidence]

12. [very weak evidence]

13. JAMA Psychiatry 2017: Glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

14. American Journal of Psychiatry 1965: A pilot study of the ketogenic diet in schizophrenia [very weak evidence]

Nutrition & Metabolism 2009: Schizophrenia, gluten, and low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diets: a case report and review of the literature [very weak evidence]

Schizophrenia Research 2017: Ketogenic diet in the treatment of schizoaffective disorder: two case studies [very weak evidence]

15. Six-month studies

Journal of Child Neurology 2003: Application of a ketogenic diet in children with autistic behavior: pilot study [uncontrolled; very weak evidence]

Metabolic Brain Disorders 2017: Ketogenic diet versus gluten free casein free diet in autistic children: a case-control study [randomized case-control; weak evidence]

Case report

Journal of Child Neurology 2013: Autism and dietary therapy: case report and review of the literature [very weak evidence]

16. This article includes a meta-analysis of seven small randomized controlled trials of elimination and low-allergen diets; while outcomes are solid, consistent and positive, there are methodological weaknesses, therefore the strength of the evidence is moderate.

American Journal of Psychiatry 2013: Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments [moderate evidence]

17. [very weak evidence]

18. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 2008: Alzheimer's disease is type 3 diabetes: evidence reviewed [strong evidence]

19. Nutrition 2011: Brain fuel metabolism, aging and Alzheimer's disease [strong evidence]

PloS One 2015: Regional brain glucose hypometabolism in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome: possible link to mild insulin resistance [weak evidence]

20. Neurobiology of Aging 2012: Dietary ketosis enhances memory in mild cognitive impairment [moderate evidence]

Nutrition & Metabolism 2012: Study of the ketogenic agent AC-1202 in mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial [moderate evidence]

Alzheimers & Dementia 2018: Feasibility and efficacy data from a ketogenic diet intervention in Alzheimer's disease [weak evidence]

Alzheimers & Dementia 2015: A new way to produce hyperketonemia: use of ketone ester in a case of Alzheimer's disease [very weak evidence]

21. [very weak evidence]

22. [clinical observation; very weak evidence]

Comment: While the studies may be lacking for making a definitive recommendation, given the extent of anecdotal evidence, it would appear that low carbohydrate, high fat diets are extremely effective for mental and behavioural symptoms. One can wait for the studies to come in, or one can consider the weight of the evidence beyond studies. A little self-experimentation may be just what the doctor ordered.

See also: