The first was in Kansas, followed by another that cut through tiny Golden City, Missouri, killing three people. Then, as the clock ticked toward midnight, a twister with EF-3 winds in excess of 135 miles per hour cut a path through Jefferson City, the state's capital, heaving bricks and turning homes into dollhouses ripped open to the sky.

A thought went through Smith's head.

"Here we go again. ... It's just part of the natural cycles of weather."

Indeed, Smith is right. Missouri and Kansas this past week were stuck in a cycle of severe weather that rolls around roughly every 15 to 20 years. The last time the region had so many back-to-back tornadoes was in May 2003.

Nothing new there, Dorothy.

But other scientists suggest that something more novel may also be stirring in the winds.

Putting politics and personal beliefs aside as to the cause of global warming (most scientists have zero doubt that it is man-made), there is no question that planet Earth is heating up. In the last 139 years, nine of the 10 warmest years on record were since 2005. The planet's temperature has increased 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit since 1901, according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment released in 2018.

Comment: There is no consensus on global warming and there is mounting evidence that the Earth is actually cooling.

Recent scientific work suggests that climate change in Kansas, Missouri and elsewhere could eventually lead to thunderstorms that are wetter and perhaps more violent, flooding - as the region saw yet again over the weekend - and more droughts.

There's no clear link between global warming and tornadoes. But in terms of twisters that upend homes and lives, a review published in October in the journal Nature adds insight.

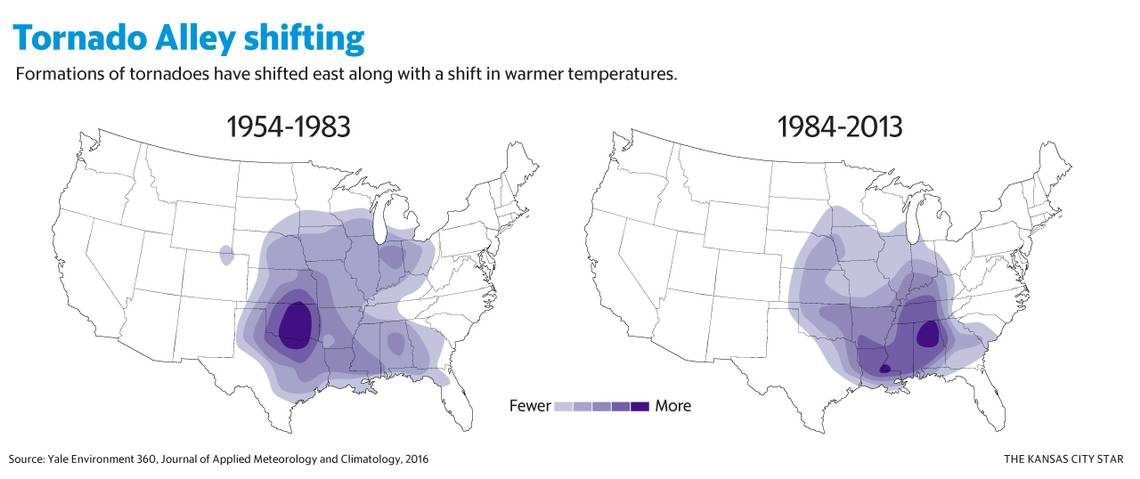

Notorious "Tornado Alley" - the band of states in the central United States, including Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas, that each spring are ravaged by hundreds of tornadoes - is not disappearing. But it seems to be expanding to include more of the Midwest and the Southeast's "Dixie Alley," a term coined in 1971.

That means a higher frequency of tornadoes in Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, Kentucky and eastern Missouri.

"Well, it is the time of the year for tornadoes. There is a lot of variability year to year," said Purdue University researcher Ernest Agee, whose work was cited in the Nature review. He looked at the distribution of tornadoes across the U.S. from 1954 to 2013.

"There is still a strong tornado season in the Central Plains, and I will say there always will be," Agee said. "There has been an increase in the Dixie Alley."

"Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri - those areas are still going to get tornadoes. I mean there's no doubt about that," said David Easterling, the director of national climate assessment for the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. "I think where you end up getting these kinds of storms is probably going to end up expanding."

In his paper, Agee says that the change "may be suggestive of climate change effects." Further research is needed to prove any link.

But a connection that scientists are making is the one between rising Earth temperature and how much water vapor is held in the atmosphere. The hotter the air, the more water vapor it holds. When that water vapor cools, it rains or pours.

"What we have actually seen is an increase in heavy rainfall events," Easterling said.

Not necessarily more thunderstorms, he said, but ones that dump more rain.

"And, of course, if you've got more heavy rainfall events, you tend to end up with more flooding," he said.

Thunderstorms, of course, spawn tornadoes. But the effect of climate change on tornadoes, he said, is unknown. Tornadoes, as severe as they can be, are still short-term weather events. Climate change looks at big-picture, long-term changes regionally or globally.

Still, Easterling said, "there is some suggestion that the environment that produces those kinds of storms may get worse with more water vapor, a little bit warmer air. But whether or not you can say that will translate into more tornadoes is a hard thing right now to answer."

Smith, the meteorologist who's retired but still studies weather and consults for science-based businesses, does not believe that climate change is affecting the tornadoes blasting across the Midwest. He maintains that there's nothing unique about the recent spate.

"This is nothing new," Smith said.

The only reason it seems bad, he said, is in comparison to more recent years.

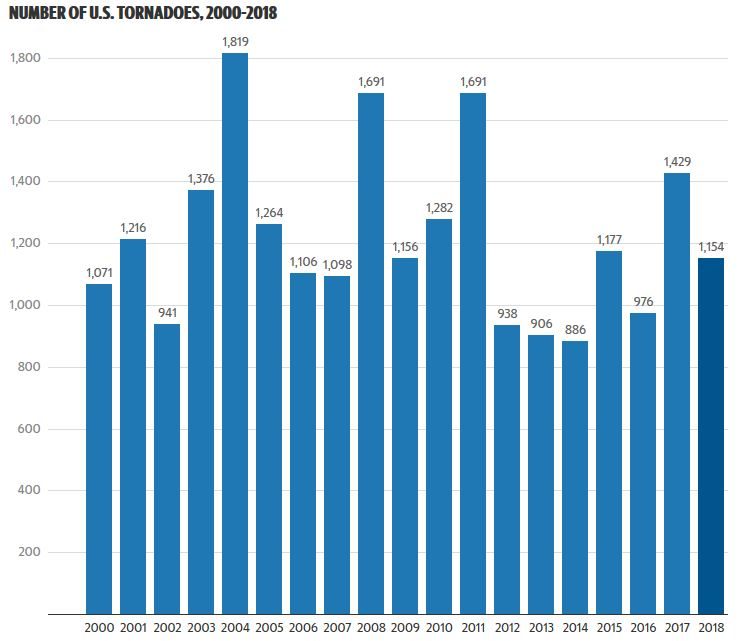

Last year, 1,154 tornadoes were reported, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The year before: 1,429. The year before that: 976. Already this year, 780 have been reported.

That's natural variability.

"One of the reasons it seems so bad is it's been so mild in recent years in the Great Plains," Smith said. He likened it to another weather phenomenon, hurricanes, that seemed to suddenly go from calm to crazy.

"We went through the longest period in entire history without a strong hurricane hitting the United States," he said of the relative calm from 2005 to 2017. "Then all of a sudden when you get Maria and Harvey and all the others, everyone goes 'Oh my gosh.'"

Harold Brooks, the co-author of the Nature paper and a research meteorologist at the National Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, Oklahoma, said that while "having a bunch of days in a row like this is rare ... it does happen."

"We understand why a big day like Wednesday happens," Brooks said. "But why we have several days in a row? We don't really have a good handle on that."

Justin Titus, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Springfield, called this tornado outbreak above normal, "but it's not that unusual."

"It happens every few years," he said. "We haven't seen a pattern like this in like 10 years or so, but it does happen."

"We just get in a stale pattern where there is a front across the area," Titus said. "As far as this being a normal springtime thing, last year we didn't see this. Next year, who knows?"

Once the winds of this spring's tornadoes die down, Kansans and Missourians may want to get a handle on something else: the growing possibly of long-term drought.

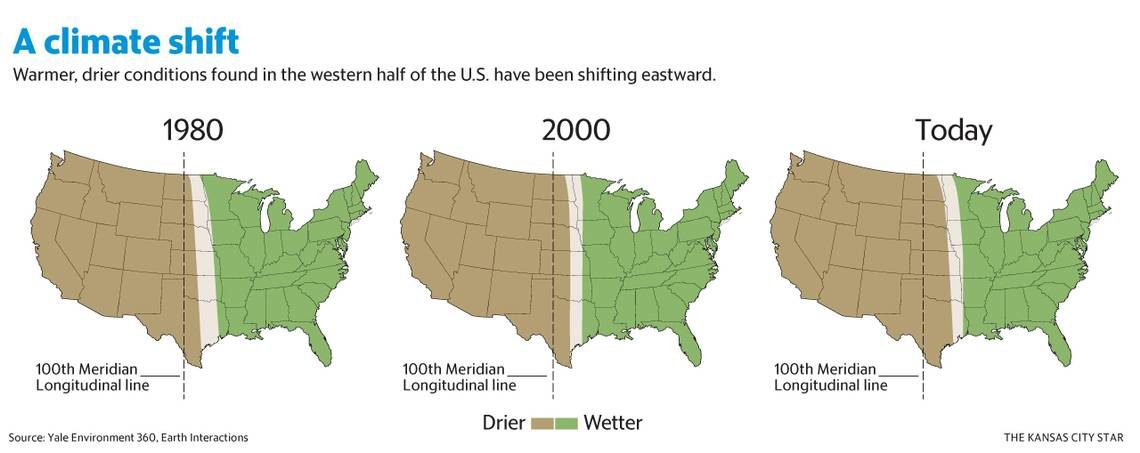

The United States is split in half by what researchers call a "transition zone": East of the zone is humid and rainy, west of the zone is dry. That transition zone once lined up with the 100th meridian, a longitudinal line that cuts through western Kansas and the Oklahoma Panhandle.

But a study last year, published by Columbia University professor and climate researcher Richard Seager, shows that line is gradually traveling east and has moved atop Kansas City.

"The climate models predict it will continue to move eastward over the coming decades," Seager said. "And that's largely because of warming temperatures."

The result? Kansas City will eventually become more arid - which, besides affecting your air conditioning, the foundation of your home and the brown patches on your lawn, will have obvious consequences for agribusiness in the Midwest.

Water-intensive crops like corn may be pushed to the east. Hardier crops like wheat will remain a staple to the west.

Seager's study didn't tie the change to severe weather, although he said it does portend increased drought to the west.

The good news: The transition happens gradually, giving people time to plan. The bad news: People are lousy at planning.

"It's not like it happens catastrophically overnight," Seager said. "It should allow some advance planning. But you know, humans tend not to do that. They tend to wait for something to happen."

Comment: See also: