A little over a year ago, LIGO was taken offline so that upgrades could be made to its instruments, which would allow for detections to take place "weekly or even more often." After completing the upgrades on April 1st, the observatory went back online and performed as expected, detecting two probable gravitational wave events in the space of two weeks.

LIGO announced the first of the two new GW events on April 8th, which was followed by a second announcement on April 12th. The signals were detected thanks to the three-facility collaboration between LIGO and the Virgo Observatory in Italy, and both are believed to have been the result of a pair of black holes merging.

By observing the source in different wavelengths (optical, X-ray, ultraviolet, radio, etc.), scientists hope to learn more about what causes GW events and about the dynamics behind them. For these latest detections, a team of scientists from Penn State University - led by Chad Hanna, an associate professor of physics, astronomy and astrophysics - played a vital role.

As Cody Messick, a graduate student in physics at Penn State and member of the LIGO team, explained:

"Penn State is part of a small team of LIGO scientists that analyze the data in almost real-time. We are constantly comparing the data to hundreds of thousands of different possible gravitational waves and upload any significant candidates to a database as soon as possible. Although there are several different teams all performing similar analyses, the analysis ran by the Penn State team uploaded the candidates that were made public for both of these detections."

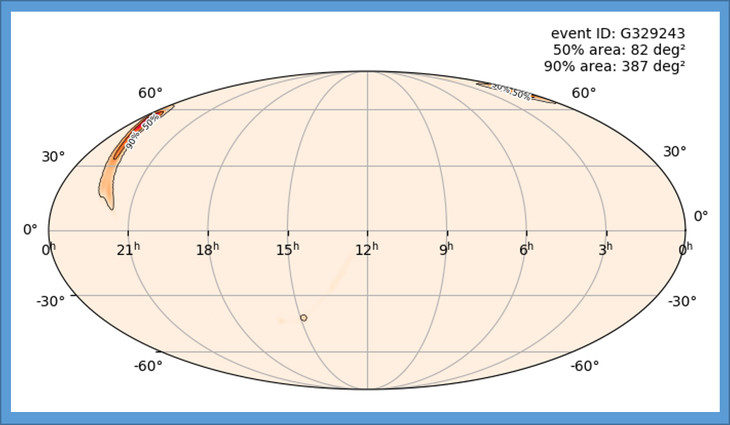

LIGO public alerts also include a sky-map that shows the possible location of the source in the sky, the time of the event, and what kind of event it is believed to be. LIGO has also said that in the future, announcements of candidate events will be followed by more detailed information once they have had a chance to properly vet and study them.

As Ryan Magee, a graduate student in physics at Penn State and member of the LIGO team, put it:

"These are near real-time detections of gravitational waves produced from two probable black holes colliding. We detected the first signal within about 20 seconds of its arrival to earth. We can set up automatic alerts to get phone calls and texts when a significant candidate is identified. I thought I was getting a spam phone call at first!"

So far, astronomers have deduced that GW events can be the result of binary black hole mergers, a merger between a black hole and a neutron star, or a binary neutron star merger. Each of these events produce gravitational waves with very different signals, which allows astronomers to determine the cause.

"This is the first LIGO observation that was made public right away in an automated fashion. This is the new LIGO policy starting with this observing run. Events are instantly made public automatically. After human vetting, a confirmation or retraction is issued within hours."

With the increased sensitivity of their detectors, the LIGO team hopes to not only make more detections, but detect a greater variety of signals. So far, events have been detected that were the result of mergers between two black holes or neutron stars. It is hoped that in the near future, the team might detect a signal produced by the merger of a black hole and a neutron star.

Whatever form the next events take, you can expect that we will be hearing about it! The public can keep track of public alerts at https://gracedb.ligo.org/latest/, or you can download the alert app at Gravitational Wave Events iPhone App.

Comment: It's worth remembering that there has been signifcant controversy surrounding the LIGO project, and, as noted in the article, the scientists can't be certain about what they're seeing, just yet:

- "An illusion": Grave doubts over LIGO's 'discovery' of gravitational waves

- Weird gravity waves pulse from a tropical cyclone

- 'Gravity Waves' in Venus clouds spotted by spacecraft

- A new type of gravitational wave has been detected... maybe

- Researchers find sound waves a source of strange 'negative' gravity

- First ever black hole image has been released

- Fast growing black hole defies the laws of physics

Also check out SOTT radio's: