Where has it gone so wrong for the man once likened among sections of the French press to a cross between Jupiter and Christ? More to the point how could The Spectator get it so wrong in running a piece last December entitled 'Macron is becoming the darling of the Deplorables'?

I can only assume that when I wrote that article, in particular the line about Macron having 'a wise head on those young political shoulders', I had come from a long Christmas lunch.

In my defence I would like to point out that I did temper my praise with some cautious prognosis. Describing Macron's adroit handling of Johnny Hallyday's funeral, for which one million mourners came to Paris, I wrote: 'Johnny's fans, the 'Deplorables', are proud of their country and its culture...[but] the support of the 'Deplorables' remains fragile, their scepticism never far from the surface, and they will move to the right should Macron start ignoring their concerns.'

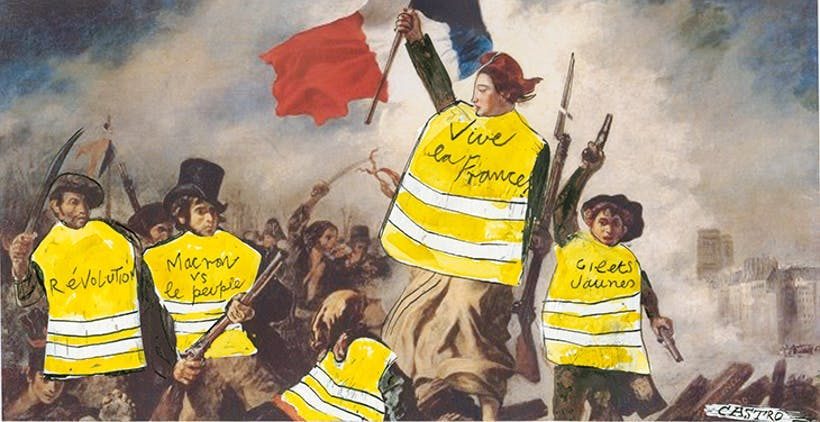

A year later those same people returned to Paris wearing yellow. They have dispersed, for the moment, but the chances are they will be back at some point in the next three and a half years of Macron's reign.

The president's descent from that lofty opinion poll was in many ways to be expected. He had campaigned on a platform of reform and modernisation, and it was inevitable that his approval ratings would take a hit when he went into action.

But few imagined his fall would be so dramatic. It's his personality as much as his policies that have alienated and infuriated the French, and also the gradual realisation that he fails to deliver. Take his visit to Washington in April. Macron went with the aim of bringing Donald Trump to heel, influencing his American counterpart's mind on climate change and the Iran nuclear deal. He got nowhere. The humiliation he felt after nearly a year of buttering up Trump was acute, so Macron vowed his revenge: he would become the antidote to Trump, the progressive president to the narrow-minded nationalist in the White House. He began issuing haughty warnings about the 'leprosy' of populism and making thinly-veiled criticisms of Italy and Hungary.

To demonstrate how progressive he was, Macron hosted an electro dance night at the Elysée Palace on June 21 for the annual Fête de la Musique event in France. His office posted a photo on social media in which the presidential couple posed among a LGBT dance troupe. It wasn't well received, with his political opponents on the right raging at the hypocrisy of the president. Earlier in the month he had given a teenager a piece of his mind for daring to hail him as 'Manu' during a walkabout. Show some respect to my office, he told the shaken youth. Yet here he was, so claimed his enemies, turning the Elysée into a gay discotheque.

There was similar criticism at the end of the September when he was photographed between two strapping semi-naked young men during a visit to the Caribbean. What dismayed the French most, other than the obscene gesture from one of the men, was how boyish their president looked.

Taken in isolation these were not significant blunders but they added to the growing perception of a president who was more interested in his image as a progressive than alleviating the social problems of his country.

Yet there was still a grudging respect for the president. He wasn't liked but there was an appreciation of the way he carried out much needed reforms to SNCF, the state railway, in the face of three months of rolling strikes by union members. His approval rating went up as a result. It was the calm before the storm.

The storm broke out of nowhere. It was July, the country was sizzling in a heatwave and French men and women were still nursing hangovers after the most memorable Bastille Day celebrations in years. Fireworks on the 14th and a World Cup win on the 15th. Macron was in Russia to see a joyously multicultural French team thrash Croatia with a dazzling display of football.

Three days later Le Monde splashed the scoop of the year across its front page: Alexandre Benalla, the president's top security aide, had been filmed beating up protestors during a May Day march through Paris. Worse, he had passed himself off as a policeman; worse still was the Elysée's response: they spun a web of mistruths, each one unravelled by subsequent media investigations.

Comment:

- Elysee Palace cover-up as Macron bodyguard caught on camera beating up protesters

- 'Let them come and get me': Macron protects bodyguard over violent May Day scandal

- Alexandre Benalla, the Rambo of Macron's 'Watergate'

- French intellectuals livid after watchdog blacklists everyone criticizing Macron-Benalla scandal as 'Russophiles'

The Benella affair, as it came to be known, was the scandal that irrevocably altered the relationship between the president and the people. Macron had promised change but he had delivered the same deceit. The grudging respect turned to furious rancour, exacerbated by the stagnating economy, the fall in purchasing power and the rise of taxes. This was reflected in the opinion polls with Macron's approval rating plummeting from August onwards.

Can Macron claw his way back towards political credibility in 2019? No. The contempt he once showed for his people, the 'Resistant Gauls' as he mocked them this year, is reciprocated. It could be heard in the chants of the gilets jaunes and seen on their graffiti sprayed on buildings in Paris, Toulouse, Bordeaux and Marseille.

The contempt has now gone viral, thanks to a young singer from Toulouse called Kopp Johnson, whose catchy ode to the protestors, gilet jaune, has been viewed more than eleven million times since he uploaded it onto Youtube. Johnson is of Congolese origin, but it's unlikely Macron will be celebrating diversity in this instance.

Macron hopes that the measures he announced earlier this month have drained the colour from the yellow vest movement. A 'grand débat' is promised for 2019, when his politicians will travel the country listening to the people's grievances, but scepticism is rampant. It has already been ridiculed as nothing more than the 'Grand Blabla'.

Whatever 2019 holds for Macron one thing is certain: he will never again rule with such brazen authority. Those days are over, and that will be hard to bear for a narcissist like Macron. Humility, not hauteur, should be his resolution for the new year.

Gavin Mortimer is a best-selling writer, historian and television consultant whose versatile narrative non-fiction books have been published in Britain and the United States. In addition he writes regularly for The Spectator about France and its politics, and he is also a regular contributor to magazines including BBC History, the History of War and History Revealed.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter