Should you pass on the meat and reach for the muffins instead?

A new study conducted at the University of Sydney and published in the journal Cell Reports is inspiring headlines around the world, like this one:

"Low-protein, high-carb diet may help ward off dementia"

In the study, scientists compared diets containing different amounts of protein and carbohydrate to a low-calorie diet. Their results suggested that diets lower in protein and higher in carbohydrate may, in some cases, provide subtle brain benefits similar to the benefits seen with calorie restriction. The researchers concluded, "A very low-protein, high-carbohydrate diet may be a feasible nutritional intervention to delay brain aging."

This, despite a growing body of clinical evidence suggesting that low-carbohydrate diets can be helpful for people with brain problems, including neurological, psychiatric, and cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer's disease. What is going on here?

If you believe in the health benefits of high-carbohydrate diets, you could take the headlines at face value and feel reassured that the study confirms your beliefs. You could point to the fact that this study represents a collaborative effort of international scientists from prestigious places like the University of Sydney, the National Institutes of Health, and Harvard University. You could even spend time skimming the 38-page paper admiring how sophisticated and impressive the science looks.

If you believe in the health benefits of low-carbohydrate diets, you could decide to dismiss this study simply because it is a mouse study, or you could spend precious time scrutinizing the results and judge them to be weak or inconclusive.

However, the best and most efficient way to evaluate this (or any) rodent nutrition study is to go straight to the methods section and look at the chow. [Caution: what you'll discover in almost every case may shock, infuriate, confuse, or entertain you, depending on your personality structure.]

Show Me the Chow

Unquestionably, the single most important thing we need to know about any diet study is the composition of the diet - yet nowhere within this report do we find a description of any of the five diets these animals were fed. All we are given is this vague reference to the chow upon which the diets were based:

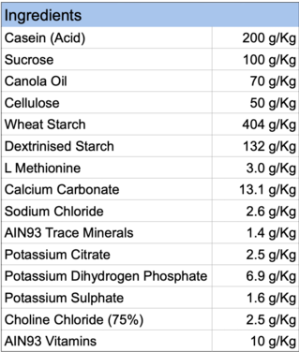

"Diets were purchased from Specialty Feeds (Perth, Western Australia) and formulated to have the same total energy content (isocaloric) but different ratios in protein to carbohydrate with fixed fat. Each diet was based on [emphasis mine] the rodent diet AIN-93G (Specialty Feeds) and formulated to contain all essential vitamins, minerals, and amino acids for growth in mice. The primary dietary protein component was casein, the main carbohydrate component was starch, and the main fat component was soy oil."To find the ingredients of base formula AIN-93G we (should not) have to do a Google search. [Chow-chasing being a favorite pastime of mine, I'm accustomed to this game.]

Notice that this "food"- made from casein (isolated milk protein), starch, sugar, and canola oil - is essentially the equivalent of a highly-processed ice cream cone, formed into mouse chow pellets.

Poor meeces.

Wild mice are "opportunistic omnivores" adapted to eat a wide variety of plant and animal foods found in the natural environment - seeds, fruits, insects, nuts, etc. The diets in this study contained no nuts, seeds, whole grains, bugs, leaves or berries.

There isn't a single mouse-appropriate healthy whole food in this formula. Just about any change researchers could have made to this diet would have been an improvement.

All Carbohydrates Are Not Created Equal

There are three types of carbohydrate in the AIN93G chow:

63 percent is wheat starch, a complex carbohydrate (long chains of glucose molecules) made by removing protein and fiber from wheat flour.

21 percent is "dextrinized" starch, a refined carbohydrate (treated with heat and acid to break its long chains of glucose molecules down into smaller, more rapidly-digestible pieces).

16 percent is sucrose, aka table sugar (50 percent fructose, 50 percent glucose).

Given everything we know about sugar and disease, one would hope that scientists interested in brain health would at least remove sugar and other refined carbohydrates from their experimental chows. Unfortunately, we aren't told what kind(s) of carbohydrate are in the experimental pellets, only that the "main carbohydrate component was starch."

The authors write that their chows were "based on" AIN93G, which contains canola oil, whereas the diets they used in the study contained soy oil. We have no way of knowing what other important differences there may have been between AIN93G and the actual diets used in the study, because the experimental diets are not described.

How does a methods section like this pass scientific peer review? Shouldn't scientists conducting dietary experiments be required to disclose the ingredients of the diets they are studying?

The Experiment

These serious concerns aside, let's look at what the researchers were trying to do. They explain that animal studies suggest calorie restriction may have positive effects on cognition and brain aging, but acknowledge that long-term caloric restriction is difficult for human beings to sustain. So, they set out to explore whether lowering protein and raising carbohydrate might have similar positive effects on the brain without the need for caloric restriction.

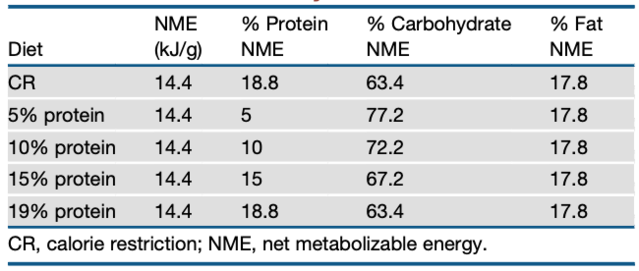

They created a chow containing 19 percent protein, 63.4 percent carbohydrate, and 17.8 percent fat to represent a standard "control" diet (listed at the bottom of their table below). They also fed some of the mice a diet that was 20 percent lower in calories by restricting them to eating a smaller amount of that standard chow (labeled "CR" for "calorie-restricted" in the top row of the table below). They then designed three lower-protein, higher-carbohydrate versions of the standard chow by replacing some of the protein with carbohydrate.

Notice that protein variation was large - ranging from between approximately 5 percent and 19 percent - so the low-protein diet contained nearly four times less protein than the high-protein diet. All five diets were very high in carbohydrate, and the variation in carbohydrate was relatively small, ranging from about 63 percent to 77 percent, meaning that the "high-carbohydrate" diet contained only about 1.2 times more carbohydrate than the standard diet. Low-carbohydrate diets of any kind were not included in this experiment.

The lower-protein, higher-carbohydrate versions of the diet replaced casein calories with carbohydrate calories - but what kind of carbohydrates? We know that AIN93G contained three types of carbohydrate, each refined to a different extent, but we don't know what kind(s) of carbohydrate were present in the experimental chows. This matters because refined carbohydrates can endanger health in ways that whole food, complex sources of carbohydrates may not. If the higher-carbohydrate chows also happened to contain less refined carbohydrate, that could have had an impact on the health effects of the diet, yet the authors do not address the question of carbohydrate quality one way or the other.

Dairy Is Different

But it's not all about the carbohydrates. Protein quality matters, too.

The only protein source in the lab chow was casein - a protein isolated from cow's milk that wild mice wouldn't naturally encounter as they scurry about their daily business. There is even research suggesting some mice may have a natural aversion to casein:

"When intact casein has been offered to rodents, there have been some reports that individuals have refused to eat it, even to the extent of suffering weight loss and death."

It is unfortunate that so many lab chows use casein extract as a protein source, because dairy protein is markedly different from the protein found in the meat of animals (mammals, birds, fish, insects, etc.) and has unique hormonal effects on the consumer, especially on insulin levels.

"Intervention studies provide evidence that dairy proteins have more potent effects on insulin and incretin secretion compared to other commonly consumed animal proteins."High insulin levels and insulin resistance have been established as key driving forces behind most cases of Alzheimer's disease and many other chronic diseases that we associate with aging. Therefore, it may indeed be wise to limit the intake of dairy protein, but what about other kinds of protein? Would the results have been different if a non-dairy protein source had been used?

The lead author of the study, Devin Wahl, a graduate student at the University of Sydney, told the Canberra Times in this interview that he believes people should minimize red meat consumption based on his research, yet there wasn't a single morsel of meat of any kind in his study.

Comment: This is extremely common in dietary "research" - not a single shred of meat is fed to the experimental rodents yet the researchers do a press release, which gets spread throughout the mainstream media, recommending everyone stop eating meat. These are ridiculously basic no-no's in science that every researcher should be familiar with.

Questioning the Science

Even if we were to take the findings of this study at face value, and accept that substantially lowering protein and modestly raising carbohydrate (from high to even higher) may indeed bring subtle brain benefits, we would still need to wonder:

- Are mice and humans supposed to eat the same amounts and types of protein and carbohydrate? The digestive tract of a mouse is markedly different from the human digestive tract because it is designed to handle a different diet - one that is much higher in fibrous plant foods.

- Is lowering protein to 5 percent of daily calories safe for human beings? According to this USDA protein calculator, a 65-year-old woman weighing 135 pounds whose activity level is low should consume 49 grams of protein per day, which represents 10 percent of her total daily calories. This estimate is based on the current international RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) for protein, which is set at 0.8 grams per kilogram body weight per day - but scientists are questioning whether this level of protein may be too low for older people. In fact, a growing body of research suggests that healthy older people may need to eat between 1.0 and 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram body weight per day (12.5 to 15 percent of daily calories) to maintain muscle mass and support optimal health, and that people with certain health problems or higher activity levels may need to eat even more than that.

What's the Real Headline?

Delving into the complexities of the study's results is not worth the time or energy when the methodology is so flawed ("garbage in, garbage out," as the saying goes), but here is how the authors summarize their cognitive and behavioral findings:

"In our study, the calorie-restricted diet and LPHC [Low-Protein-High-Carbohydrate] diets were associated with modest improvements in behavioural and cognitive outcomes, although results were mainly limited to females and inconsistent."Every chow in this study was made from junk food. At best, this study can only inform us about the risks and benefits - to mice - of eating junk food containing various percentages of protein and carbohydrate. We have no idea what the findings mean for people who eat minimally-processed, species-appropriate foods.

A more accurate headline might look something like this:

If your diet consists entirely of ultra-processed mystery pellets made from dairy protein extract, refined starches, sugar, and soybean oil, and you are a mouse, your brain may be slightly better off if you switch to mystery pellets much lower in dairy protein extract and a little bit higher in refined starches and/or sugar. We're not going to tell you exactly how much sugar, starch or dextrinized starch should be in your pellets, but we don't think you should worry about such details. Instead, we'd like you to simply believe that more carbohydrate is always good (regardless of degree of refinement), protein (by which we hope you'll assume we mean meat) is bad, and that we have conducted a serious study relevant to human nutrition that is worthy of your consideration.The unfortunate truth is that this study was simply not designed in a way that can tell you anything about human diets, meat, or how much protein or carbohydrate you should eat.

Georgia Ede, MD, is a Harvard-trained psychiatrist and nutrition consultant practicing at Smith College. She writes about food and health on her website DiagnosisDiet.com.

Comment: The dishonesty in the reporting of nutritional science, both from the media and the researchers themselves, is at such an epic level at this point it's a wonder anyone at all believes what the media has to say about diet. Everyone is much, much better off doing their own research and taking cautious experimental approaches with what they find. The message given to the masses has an agenda, and it isn't to get the population any healthier.

See also: