The discovery points to the existence of a social support system for disabled people in Canaanite settlements of the late Bronze Age, archaeologists say. More broadly, it also highlights that while we may often think of antiquity as a time of brutality and survival of the fittest, it isn't necessarily so.

By caring for the weak, the Canaanites were merely obeying a social imperative that seems to have predated humanity. Even the Neanderthals are thought to have significantly helped their disabled brethren. Also Homo erectus, who evolved some 2 million years ago, may have noticed each other's pain, and helped each other out, based on the discovery of an aged, toothless erectus individual found in Dmanisi, Georgia who likely couldn't have survived on its own.

The Canaanite tomb, dated between the late 16th and early 15th centuries B.C.E., was found in 2016 underneath a building on the ancient site. This was not a surprise: it was common at the time to bury the deceased under the floor of the family home, says Rachel Kalisher, a bio-archaeologist and PhD student at Brown University.

What was surprising was the condition of the skeletons inside the burial, says Kalisher, who presented the results of her study of the bones earlier this month at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research in Denver.

One skeleton displayed multiple anomalies, including what is described as a metopic suture - meaning the bones of the forehead had not fused in infancy as they should have. The person also had a rare fourth molar (most adults have three molars in each quadrant of the mouth, the third being the wisdom tooth).

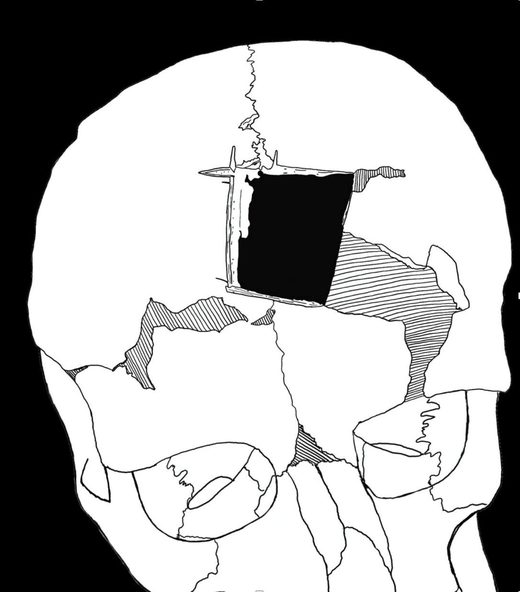

Most intriguingly, his skull was missing a square chunk of bone right on the forehead. He had undergone trephination, a surgical procedure not rare in the ancient world, that involved drilling a hole into the patient's skull, Kalisher explains.

Both skeletons showed signs of cribra orbitalia, which are lesions on the upper eye sockets that are likely connected to anemia in childhood.

The two men also suffered from a condition that caused severe damage to their entire skeleton, resulting in lesions and porous holes in their bones. The condition would have been extremely painful and may have impacted their mobility, Kaslisher says. In contrast to the extra molar, for instance, this was not a congenital problem but an infection they both contracted at some time in life, though genetic predisposition may have played a role, she says.

So far , DNA analysis of the two skeletons has shown that the two men were brothers, the archaeologist says.

Her analysis concluded that the first man, the one with trephinated skull, died between the age of 20 and 40, while his brother, who is believed to have died much earlier, survived only until his early twenties.

A sketch reconstructing how the trephinated skull found in Megiddo looked. Rachel Kalisher

While neither lived to a ripe old age, they obviously survived for many years despite their health problems. This is also confirmed by the analysis of the teeth, which can reveal if a person has been malnourished in childhood.

Poor nutrition is commonly found in human remains from Megiddo, even among healthy individuals. But this was not the case for the two brothers, Kalisher reports. There were also comparatively few signs of dental wear on the teeth, suggesting they ate non-abrasive food and didn't use their choppers as tools - as many people commonly did at the time.

"There was some kind of support mechanism in place, they were well fed and taken care of throughout their lives," Kalisher tells Haaretz. "There was also some sort of medical care, since someone came and performed surgery on this person, and the surgery was well done."

When drilling a hole in the skull is a good idea

Trephination was practiced by cultures all around the globe, from ancient Greeks and Romans to the pre-Columbian societies of South America.

In the ancient Middle East it was not particularly common, says Kalisher, adding that that only about a dozen other cases have been found in the region, dating from the Neolithic to the Hellenistic period. This was the first evidence of trephination (also called trepanning) at Megiddo, she said.

Throughout history, reasons for performing trephination have ranged from the medically sound to purely ritualistic and irrational. The procedure could be used to "clean" a skull fracture or relieve pressure on the brain caused by the swelling and fluid buildup that can follow a head injury. But it was also seen as a way to release evil spirits that were believed to afflict people with some mental or neurological disorders.

While skull surgery in a time without antibiotics and anesthesia may sound like a death sentence for the patient, some people did survive the procedure, as demonstrated by the bone regrowth found on many trephinated skulls around the world. Some studies have suggested the survival rate of this dramatic surgery could have been around 80 percent.

In the case of the Megiddo skull, no bone regrowth can be seen, indicating that the man died within a week of the operation, Kalisher says.

The archaeologists also found most of the bone pieces that had been removed from the skull because they had been buried with the patient.

The surgery may have failed because it was performed on the forehead, right over the metopic suture. Ancient people knew better than to drill holes into the sutures of the skull because these areas are directly above large blood vessels, increasing the chances of the patient bleeding out, Kalisher says.

In this case, the local surgeon could not have known that this patient had an additional, anomalous suture on the forehead.

"Obviously, it didn't end well, but we can't say whether the surgery killed him," Kalisher notes. "This person had lived with disease for a long time and things must have been escalating for there to be a need for this surgery, so he may have been already dying at the time."

Not all researchers are convinced the procedure can be described as a trephination. Had it been done for medical purposes, a round hole would have been drilled into the skull, because this facilitated healing, postulates Israel Hershkovitz, a Tel Aviv University physical anthropologist who did not participate in the study. The fact that the hole in this case was roughly square, suggests it was done for ritual or even violent purposes, he suggests.

A good 'hood

While the exact cause of death for both brothers remains unclear, what is clear is that in death they continued to be respected and cared for. The two men were found buried close to the city's Late Bronze Age palace, in an area where archaeologist have found remains of solidly-built houses and evidence of higher-quality food, says Israel Finkelstein, the Tel Aviv University archaeologist who directs the dig at Megiddo.

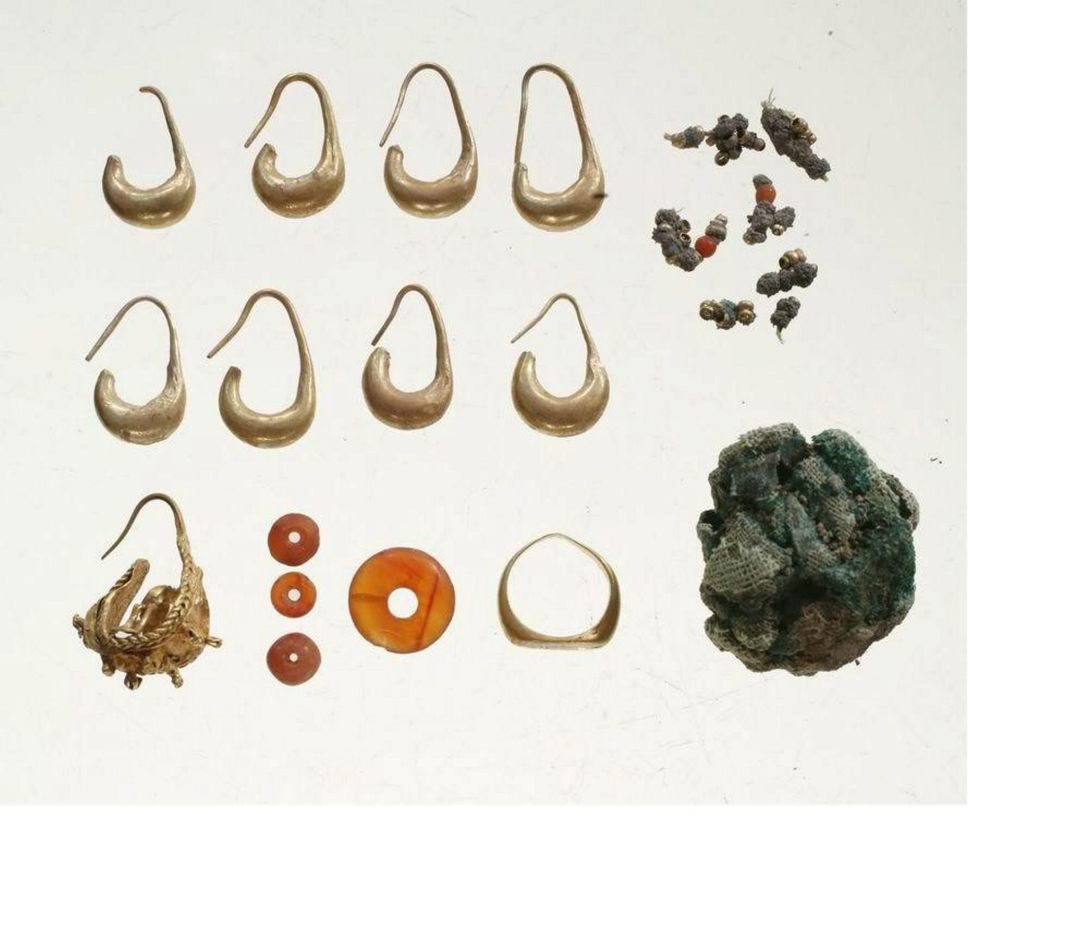

The tomb of the brothers was dug almost exactly above a recently-discovered elite burial which included three skeletons adorned with silver and gold jewelry.

This so-called "royal tomb" predated the brothers' burial by about a century, though it is likely that the two were linked, says Finkelstein: "It is not a coincidence that [the brothers] were buried so close: they must have known that this previous important tomb was there and they tried to connect to it, either for ritual purposes or because there was some dynastic link."

In the case of the brothers, the funerary offerings were dignified if not as lavish as in the older tomb. Archaeologists found pottery vases, including a bichrome jug imported from Cyprus decorated with the image of a fish and a bird, and a single bead decorating one of the skulls.

Some 3600 years ago, Megiddo was one of the most important and prosperous Canaanite cities, controlling one of the main international trade routes running through the Levant. Shortly after the brothers' death, in the mid 15th century B.C.E., it was conquered by the Egyptians and would later feature prominently in the biblical narrative. It was the site of numerous bloody battles throughout the centuries, likely spawning the prophecy that the final conflict between good and evil would take place there, at Armageddon (a Greek corruption of the Hebrew name Har Megiddo - Mount Megiddo).

But the tomb of the Canaanite brothers is a reminder that Megiddo was not just the site of biblical stories and apocalyptic prophecies: it was a spot that was inhabited for some 6,000 years by real people with real lives.

It's impossible to say what exactly motivated the people of Megiddo to support the two brothers during their difficult existence. But Kalisher notes the apparent universal drive in human and even, as said, pre-human civilizations to care for those who cannot provide for themselves. The Neanderthals line split off from Homo sapiens around 700,000 years ago, it seems. If they cared for their disabled kin as we do, it indicates that our ancestors may have as well.

In fact, archaeologists have recently confessed to some surprise at the apparent prevalence of disability in the prehistoric and ancient world. One possible explanation for the high rate of prehistoric disability, suggested by Erik Trinkaus of Washington University who identified 75 malformations in 66 sets of ancient remains over 200,000 years, is inbreeding.

As for the Canaanites who cared for the malformed brothers, we can't know anything about their emotional motivation, Kalisher says. "We can't say for a fact that this was done out of compassion and that they loved their disabled babies as much as their other babies. But they were definitely cared for and I would be very surprised if there wasn't also an emotional bond involved."

Or was it more accurate to say Northern Palestine,stolen,now violently occupied by mongolian kazharstani practitioners of talmudism.