The court is holding its judgment for five days, according to representatives for supporters and opponents of the law, to give the state time to file an emergency appeal.

"We're very satisfied with the court's decision today," said Stephen G. Larson, lead counsel for a group of doctors who sued in 2016 to stop the law. "The act itself was rushed through the special session of the Legislature and it does not have any of the safeguards one would expect to see in a law like this."

The state plans to seek expedited review in an appellate court, according to Attorney General Xavier Becerra, who said in a statement that he strongly disagreed with the ruling.

Assemblywoman Susan Talamantes Eggman, the Stockton Democrat who carried the bill, said Californians who are in the process of obtaining life-ending drugs through the law have had "the carpet ripped out from under their feet."

"It's a reminder for all of us that there are those out there who would like to take our rights away," she said. "When we move forward, there are those who would like to drag us back."

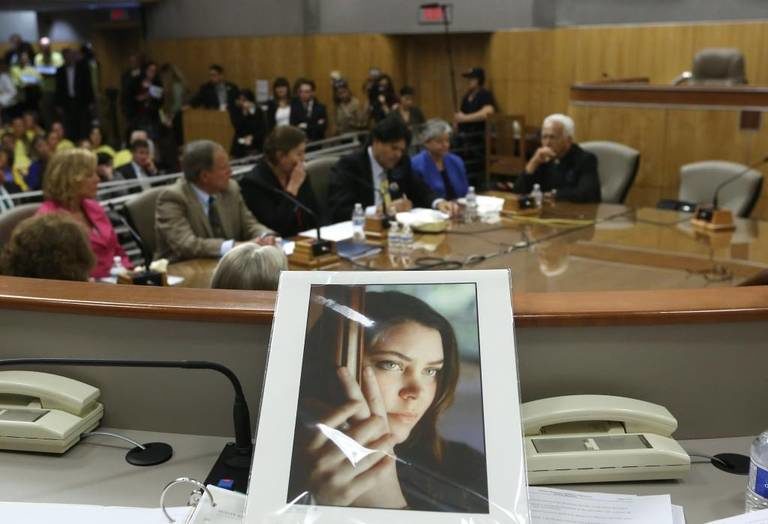

Signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in 2015, the assisted death law allows doctors to prescribe lethal drugs to patients with six months or less to live. Hundreds of Californians have already taken advantage of that option, including 111 individuals who died from taking the drugs in the first seven months of their availability.

Proponents say it provides dignity to terminally ill patients by affording them more control over the end of their lives.

But the legislative push originally fell short amid opposition from oncologists, Catholic hospitals, clergy and disability rights groups, who argued that the policy was immoral and could have a detrimental impact on health care for the state's most vulnerable patients.

After failing in regular session, lawmakers successfully revived the assisted death proposal in a special session called that summer by Brown to find a source of funding for public health programs.

Larson said his clients are most concerned about a lack of protections in the law, including an inadequate definition of terminal illness and a provision exempting doctors who prescribe the lethal drugs from liability. But he said they also challenged the manner in which the law was passed, an argument the judge sided with on Tuesday.

"That special session was called to address funding shortages caused by Medi-Cal," Larson said. "It was not called to address the issue of assisted suicide."

Supporters noted that the ruling was not about the legality of assisted death and that public polls have indicated the law has widespread approval in California. Advocacy group Death With Dignity National Center sent out a fundraising email Tuesday afternoon decrying "shadowy, religious-right groups attempting to derail the law any way they can" for "disrespecting the will of the people."

Eggman said Brown would have known "what he intended with the breadth of the special session," which also included objectives to "improve the efficiency and the efficacy of the health care system," and he signed the law.

Compassion & Choices, the organization that led the effort to legalize assisted death in California, also objected to the judge's interpretation.

"He's not acknowledging it's a health care issue, even though we believe it is," spokesman Sean Crowley said. "It deals with medication."

In fact, the proposal lost by only two votes of the assembled bishops, who numbered about 160. Reincarnation, which is the only dogma that makes any sense, was widely believed by the early Christians, but has been eliminated from Christianity and Islam, unlike Buddhism, Hinduism, and all the religions of the East.

If Christianity still retained the truth of reincarnation, the churches would not be empty now that thinking people have called Christianity's God a sadist, for allowing humans only one chance to live the perfect life, in spite of whatever adverse circumstances they were born into, and if they fail they burn for ever in Hell. This concept is so incongruous with a loving God, that nobody believes it any more, or even believes in a life after death, not even those who try to convince themselves that mouthing, "Jesus, Jesus" at the moment of death will gain them entry into Heaven instead of Hell.

Christian dogma is preposterous and idiotic.

And the end result is that all these so-called Christians cannot allow people to die with dignity, but insist they must suffer agony to the bitter end, all in the name of their "loving God." Had Christian dogma not been founded on an enormous lie, that we only get one chance at life, this cruelty in the name of a vicious and sadistic "God" would not be allowed.