These days, though, a book may get an additional check from an unusual source: a sensitivity reader, a person who, for a nominal fee, will scan the book for racist, sexist or otherwise offensive content. These readers give feedback based on self-ascribed areas of expertise such as "dealing with terminal illness," "racial dynamics in Muslim communities within families" or "transgender issues."

"The industry recognizes this is a real concern," said Cheryl Klein, a children's and young adult book editor and author of "The Magic Words: Writing Great Books for Children and Young Adults." Klein, who works at the publisher Lee & Low, said that she has seen the casual use of specialized readers for many years but that the process has become more standardized and more of a priority, especially in books for young readers.

Sensitivity readers have emerged in a climate - fueled in part by social media - in which writers are under increased scrutiny for their portrayals of people from marginalized groups, especially when the author is not a part of that group.

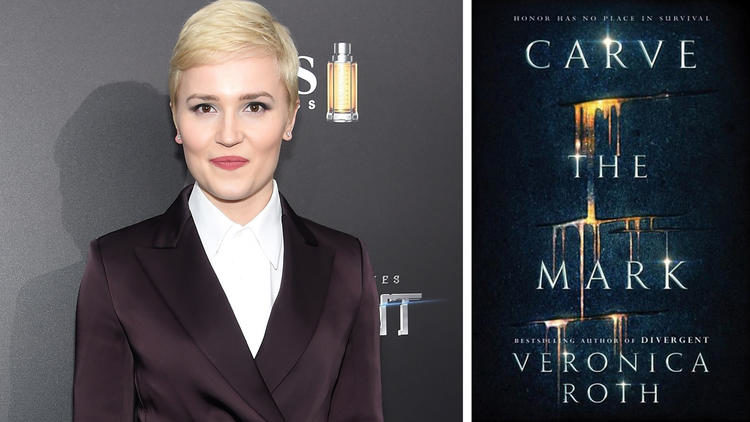

Last year, for instance, J.K. Rowling was strongly criticized by Native American readers and scholars for her portrayal of Navajo traditions in the 2016 story "History of Magic in North America." Young-adult author Keira Drake was forced to revise her fantasy novel "The Continent" after an online uproar over its portrayal of people of color and Native backgrounds. More recently, author Veronica Roth - of "Divergent" fame - came under fire for her new novel, "Carve the Mark." In addition to being called racist, the book was criticized for its portrayal of chronic pain in its main character.

This potential for offense has some writers scared. Young-adult author Susan Dennard recently hired a fan to review her portrayal of a transgender character in her "Truthwitch" series.

"I was nervous to write a character like this to begin with, because what if I get it wrong? I could do some major damage," Dennard said. But, she added, she felt the voice of the character was an important one that wasn't often portrayed, so she hired a fan, who is a transgender man, just to be sure she did it right.

For authors looking for sensitivity readers beyond their fan base there is the Writing in the Margins database, a resource of about 125 readers created by Justina Ireland, author of the YA books "Vengeance Bound" and "Promise of Shadows." Ireland started the directory last year after hearing other authors at a writing retreat discuss the difficulties in finding people of different backgrounds to read a manuscript and give feedback about such, well, sensitive matters.

One reader for hire in Ireland's database is Dhonielle Clayton, a librarian and writer based in New York. Clayton reviews two manuscripts per month, going line by line to look at diction, dialogue and plot. Clayton says she analyzes the authenticity of the characters and scenes, then points writers to where they can do more research to improve their work.

Clayton, who is black, sees her role as a vital one. "Books for me are supposed to be vehicles for pleasure, they're supposed to be escapist and fun," she says. They're not supposed to be a place where readers "encounter harmful versions" and stereotypes of people like them.

Ireland underscores the value of sensitivity readers - both for authors and for readers. (She was a strong voice behind the push to get Keira Drake to make changes to the advance readers' edition of "The Continent.")

"Even if authors mean well, even if the intention is good, it doesn't change the impact," Ireland said. "It's nice to be that line of defense before it gets to readers, especially since the bulk of people who come to me write for children." Fees for a sensitivity readers generally start at $250 per manuscript.

Children's book author Kate Messner has used sensitivity readers for many of her books, some of which deal with poverty, abuse and race.

"I wouldn't dream of sending those books out into the world without getting help to make sure I'm representing those issues in a way that's realistic and sensitive," she said. Messner, whose works include "The Seventh Wish" and "All the Answers," asks a reader for feedback on whether the experience she's written reads realistically or whether anything stands out as problematic.

Her upcoming book, tentatively called "Breakout," focuses on three girls coping with a prison escape in their small town. Messner has enlisted multiple sensitivity readers to help her work out the class and race issues affecting the town and her characters. A reader has called out when her language doesn't ring true, and has questioned when her character does something that seems inauthentic and provides her perspective on why that is. Messner said it's been encouraging to hear when she's gotten something correct, but also she's had to make adjustments.

Lee & Low Books has a companywide policy to use sensitivity readers. Stacy Whitman, publisher and editorial director of Lee & Low's middle-grade imprint Tu Books, said she will even request a sensitivity reader before she chooses to acquire a book to publish.

"It's important for authors to consider expert reader feedback and figure out how to solve the problems they point out," Whitman said. "Everyone's goal is a better book, and better representation contributes to that."

Still, some sensitivity readers feel they are in part contributing to the problem. Clayton said she's unsettled by the idea that she's being paid for her expertise, but also is helping white authors write black characters for books from which they reap profit and praise.

"It feels like I'm supplying the seeds and the gems and the jewels from our culture, and it creates cultural thievery," Clayton said. "Why am I going to give you all of those little things that make my culture so interesting so you can go and use it and you don't understand it?"

Concerns about cultural appropriation have been around for years - think of William Styron writing as the slave Nat Turner in 1967. ("That's what we're paid to do, isn't it?" Lionel Shriver said in a controversial speech last year. "Step into other people's shoes, and try on their hats.")

But sensitivity readers introduce a new twist in the debate. On the one hand they help a writer create the experience of a marginalized group more authentically. On the other, they legitimize the mimicking of marginalized voices by non-marginalized writers.

Why not just publish more books by black people, Latinos, Native Americans and others? some ask.

Despite the efforts of groups like We Need Diverse Books, "it's more likely that a publishing house will publish a book about an African-American girl by a white woman versus one written by a black woman like me," Clayton says.

"So until publishing is equitable and people are still writing cross-culturally," Clayton points out, "sensitivity reading is going to be another layer of what's necessary in order to make sure that representation is good."

Comment: Its understandable that authors would want to portray their characters in a culturally realistic way but certain social climates, like this one, fear of offending peoples' delicate sensibilities can override an author's artistic license.