Trigger Warning: This essay is about obesity - the condition of being fat or overweight. It is about being overweight, body size, fatness; it is about all the problems that accompany that condition. If reading about these topics will cause you any emotional distress or make you feel unsafe or threatened in any way - stop reading here.Stephen Hawking is a very smart guy, a very very smart guy. But like some smart guys in other fields, he can make very foolish statements based on ideas that are commonly believed but almost entirely inaccurate.

In a video produced by Gen-Pep, a Swedish non-profit organization "that works to spread knowledge and get people involved in promoting the health of children and young people", Hawking made the following statements:

[Important Note: Stephen Hawking, as you probably know, is and has been severely physically handicapped, suffering from ALS, and has been wheelchair bound since the late 1960s. His experiences with diet and exercise are not, by necessity, the same as for you and me. Neither human physiology nor human medicine are his fields of study. I do not know why he was called upon to make this promotional video for Gen-Pep.]

Hawking starts off by saying: "At the moment, humanity faces a major challenge and millions of lives are in danger..."When Hawking says these things he is simply repeating the official opinions of almost every major medical and health organization in the world:

"As a cosmologist I see the world as a whole and I'm here to address one of the most serious public health problems of the 21st century."

"Today, too many people die from complications related to overweight and obesity."

"We eat too much and move too little."

"Fortunately, the solution is simple."

"More physical activity and change in diet."

The US Surgeon General:

"... the fundamental reason that our children are overweight is this: Too many children are eating too much and moving too little.The UK's National Health Service:

In some cases, solving the problem is as easy as turning off the television and keeping the lid on the cookie jar."

"Obesity is generally caused by eating too much and moving too little."

The UN's World Health Organization:

"The fundamental cause of obesity and overweight is an energy imbalance between calories consumed and calories expended. Globally, there has been:The National Institutes of Health tell us:

an increased intake of energy-dense foods that are high in fat;

and

an increase in physical inactivity due to the increasingly sedentary nature of many forms of work, changing modes of transportation, and increasing urbanization."

"What Causes Overweight and Obesity?Of course, the NIH goes on to list the following as "other causes...":

Lack of Energy Balance

Overweight and obesity happen over time when you take in more calories than you use.

An Inactive Lifestyle

People who are inactive are more likely to gain weight because they don't burn the calories that they take in from food and drinks."

"Environment, Genes and Family History, Health Conditions, Medicines, Emotional Factors, Smoking, Age, Pregnancy and Lack of Sleep"

Everyone knows that the causes of obesity are eating too much and not exercising enough. All the major federal agencies, the United Nations, and the learned societies agree.

So how is this a Modern Scientific Controversy?

Simple: They are all wrong. Just how wrong are they on this issue? Just how wrong is Stephen Hawking on this issue?

Almost entirely wrong.

Bruce Y. Lee, associated with the Global Obesity Prevention Center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, was so concerned by Hawking's message that he was prompted to write an article for Forbes magazine titled "Stephen Hawking Is Right But Also Wrong About Obesity".

Let me be perfectly clear: The obesity epidemic is a major challenge for medical science and public health because, quite simply, we have almost no idea whatever as to the true cause(s) of the phenomena, or, in another sense, we have too many ideas about the cause(s) of obesity.

In fact, Gina Kolata, in the Health section of the NY Times, says that Dr. Frank Sacks, a professor of nutrition at Harvard,

"...likes to challenge his audience when he gives lectures on obesity.Dr. Lee Kaplan, director of the obesity, metabolism and nutrition institute at Massachusetts General Hospital, is quoted by Kolata as saying:

"If you want to make a great discovery," he tells them, figure out this: Why do some people lose 50 pounds on a diet while others on the same diet gain a few pounds?

Then he shows them data from a study he did that found exactly that effect.

Dr. Sacks's challenge is a question at the center of obesity research today. Two people can have the same amount of excess weight, they can be the same age, the same socioeconomic class, the same race, the same gender. And yet a treatment that works for one will do nothing for the other."

"It makes as much sense to insist there is one way to prevent all types of obesity — get rid of sugary sodas, clear the stores of junk foods, shun carbohydrates, eat breakfast, get more sleep — as it does to say you can avoid lung cancer by staying out of the sun, a strategy specific to skin cancer."But wait, what about our beloved Stephen Hawking's "Fortunately, the solution is simple. More physical activity and change in diet."? Well, frankly, that is not just wrong, that's utter nonsense.

Dr. Kaplan and his associates have identified, so far, fifty-nine (59) different types of obesity.

Dr. Stephen O'Rahilly, head of the department of clinical biochemistry and medicine at Cambridge University, and his group, have identified 25 genes "with such powerful effects that if one is mutated, a person is pretty much guaranteed to become obese."

Many of these genetic disorders are on the rare side, but Ruth Loos and her team at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, have other evidence - that any one of 300 different genes may be involved in the tendency to overweight, and that each gene can add to the effect of the others—add to the genetic propensity for overweight and obesity. "It is more likely that people inherit a collection of genes, each of which predispose them to a small weight gain in the right environment....each may contribute just a few pounds but the effects add up in those who inherit a collection of them."

There are more than three dozen available therapies (Dr. Kaplan claims to have 40 at his disposal) for overweight and obesity, and 15 different drugs. Using them is guided by experience and plain old-fashioned trial-and-error.

Bariatric surgery, in which the size of the stomach is physically altered by various means, is a drastic last resort for the profoundly obese.

Only the last mentioned treatment, bariatric surgery, is universally successful at bringing about a major and permanent reduction in the body weight of the obese.

In June of 2013, the American Medical Association announced that it had classified obesity as a disease. This event was covered by the NY Times - in the business - not science—section:

"The American Medical Association has officially recognized obesity as a disease, a move that could induce physicians to pay more attention to the condition and spur more insurers to pay for treatments.The move by the AMA was hugely controversial within the medical community. In fact, it prompted an editorial from the editors of the journal of the Australian Medical Association, Lee Stoner and Jon Cornwall, titled "Did the American Medical Association make the correct decision classifying obesity as a disease?"

In making the decision, delegates at the association's annual meeting in Chicago overrode a recommendation against doing so by a committee that had studied the matter.

"Recognizing obesity as a disease will help change the way the medical community tackles this complex issue that affects approximately one in three Americans," Dr. Patrice Harris, a member of the association's board, said in a statement. She suggested the new definition would help in the fight against Type 2 diabetes and heart disease, which are linked to obesity."

"The vote of the A.M.A. House of Delegates went against the conclusions of the association's Council on Science and Public Health, which had studied the issue over the last year. The council said that obesity should not be considered a disease mainly because the measure usually used to define obesity, the body mass index, is simplistic and flawed."

"The American Medical Association (AMA) recently classified obesity a disease, defining obesity as having a Body Mass Index (BMI) measure above 30. This decision went against the advice of its own Public Health and Science Committee, and has sparked widespread discontent and discussion amongst medical and healthcare communities. The fact that this classification has been made has potential ramifications for health care around the world, and many factors need to be considered in deciding whether the decision to make obesity a disease is in fact appropriate."The Australian Medical Association's editorial wraps up with this:

"Are we classifying obesity correctly?

"Before considering whether obesity should be considered a disease, we must question the suitability of BMI as a rubric. The assumption is that the ratio between height and weight provides an index of body fatness. However, there is an imperfect association between BMI and body fatness, and BMI does not and cannot distinguish adipose type and distribution. While total body fat is important, studies have shown that central adiposity (e.g., visceral fat) poses a higher risk for developing disorders associated with obesity than overall body fatness. There are superior anthropometric indices of central adiposity, including waist-to-hip ratio, yet BMI continues to be the criterion owing to previous widespread and historical use despite its obvious shortcomings. Using the BMI tool, incorrect clinical categorisation of "overweight" or "obese" is common. Therefore, this editorial accepts that the AMA has selected an imperfect tool for classifying obesity, and will hereafter focus on the theoretical notion of obesity."

"Undeniably, obesity is a risk factor associated with a clustering of complications, including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and type 2 diabetes, each of which independently and additively increase cardiovascular disease risk. However, obesity is exactly that—a risk factor. Being obese does not necessarily equate to poor health, despite the hormonal alterations that are associated with high body fat. Strong evidence has emerged suggesting that an adult may be "fat but fit", and that being fat and fit is actually better than being lean and unfit."

"Conclusion

Obesity has reached pandemic proportions, is strongly associated with myriad co-morbid complications, and is leading to a progressive economic and social burden. However, being obese does not necessarily equate to poor health, and evidence suggests individuals may be fat but fit. Perhaps most importantly, labelling obesity a disease may absolve personal responsibility and encourage a hands-off approach to health behaviour. This knowledge raises the question of morality, as individuals must now choose whether they will invest effort into maintaining a healthy lifestyle in order to free society of the healthcare burden associated with obesity. Given the myriad issues surrounding the decision to classify obesity in this way, perhaps a new question should be posed in order for society to continue this discussion: who benefits most from labelling obesity a disease?"And what about a cure? Is it possible, short of radical invasive surgery, to help an obese person permanently lose enough weight to become a normal weighted person?

If the learned societies, and Stephen Hawking, are correct in stating that obesity is as simple as eating too much and exercising too little, then the obvious cure is to take obese people, feed them less and exercise them more.

Let's go back and look at the results from Dr. Frank Sacks, professor of nutrition at Harvard, and his study "Comparison of Weight-Loss Diets with Different Compositions of Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrates".

ResultsDigging in a little more, we find that:

At 6 months, participants assigned to each diet had lost an average of 6 kg [13 lbs], which represented 7% of their initial weight; they began to regain weight after 12 months. By 2 years, weight loss remained similar in those who were assigned to ...[the four diets, ranging from 6 to 9 lbs]...Among the 80% of participants who completed the trial, the average weight loss was 4 kg [ 9 lbs]; 14 to 15% of the participants had a reduction of at least 10% of their initial body weight. Satiety, hunger, satisfaction with the diet, and attendance at group sessions were similar for all diets; attendance was strongly associated with weight loss (0.2 kg per session attended). The diets improved lipid-related risk factors and fasting insulin levels.

"At 2 years, 31 to 37% of the participants had lost at least 5% of their initial body weight, 14 to 15% of the participants in each diet group had lost at least 10% of their initial weight, and 2 to 4% had lost 20 kg [45 lbs] or more (P>0.20 for the comparisons between diets)."These are serious weight loss diets, closely supervised, with group and individual reinforcement sessions, for 2 years. Only 2 to 4% of the participants lost truly substantial amounts of weight that would reclassify them as normal weight persons. The rest of the participants lost those easy first 10-15 pounds in the first six months, but after a year, they began to regain their lost weight, despite staying on the diet and receiving group counseling, to end up with average loss, for 80% of the participants, of 9 pounds [4 kg], after two years of supervised dieting.

Let's see what these results mean for those suffering from obesity:

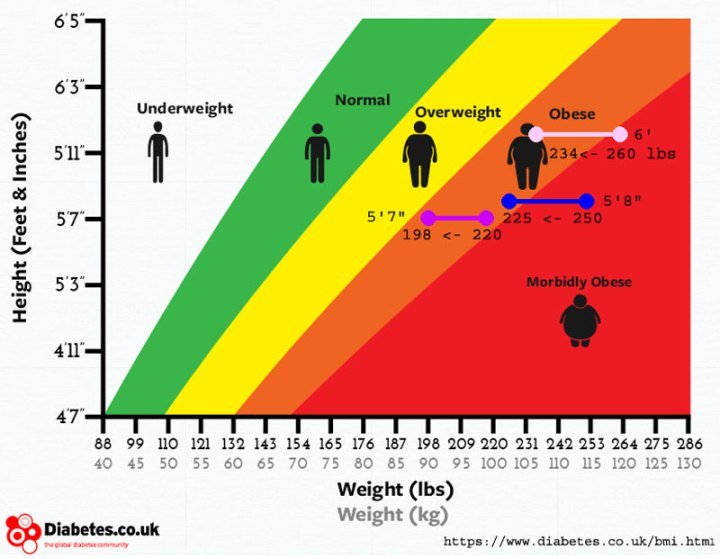

I've added three colored dumbbells, showing just what a permanent 10% reduction in body weight means for three sample obese patients. Two have managed to move from Morbidly Obese to Obese, and one is still Obese. We have not considered the more extreme cases, which are not rare - persons weighing > 286 lbs. You can picture for yourself what the loss of 9 lbs would represent for you or someone you know who is far too heavy.

The real finding is that under a strict diet, most people can generally (but not always) lose 10-15 pounds if they are supported by counseling (professional or family). With care, these people can keep most of those extra pounds off. This benefits those whom who (h/t jsuther2013) are classified Overweight, but not generally those that are truly Obese, who remain obese after this weight loss. Nonetheless, medical bio-markers do improve even with these fairly small weight loses. Whether this improvement in bio-markers adds up to improved health and longevity is not known.

It is important to note that the above chart is based on the metric BMI which is under serious doubt within the obesity research community.

25 genes guaranteed to make you obese; 300 genes that add to each other to pack on pounds; 56 different types of obesity; 15 drugs; 40 therapies; three or four surgical approaches...definitely not simple, Mr. Hawking.

But that's not all.

Erin Fothergill's "Biggest Loser" study found:

"In conclusion, we found that "The Biggest Loser" participants regained a substantial amount of their lost weight in the 6 years since the competition but overall were quite successful at long-term weight loss compared with other lifestyle interventions. Despite substantial weight regain, a large persistent metabolic adaptation was detected. Contrary to expectations, the degree of metabolic adaptation at the end of the competition was not associated with weight regain, but those with greater long-term weight loss also had greater ongoing metabolic slowing. Therefore, long-term weight loss requires vigilant combat against persistent metabolic adaptation that acts to proportionally counter ongoing efforts to reduce body weight."What this means is that a person's body fights back against weight loss and adapts its base metabolic rate to burn fewer calories while resting in an apparent attempt to regain weight lost by dieting and thus maintain a set weight point under conditions of lower caloric intake. This study was such big news that it is featured in the New York Times' "Medical and Health News That Stuck With Us in 2016".

Eleonora Ponterio and Lucio Gnessi, in their study "Adenovirus 36 and Obesity: An Overview" report that:

"...the data indicating a possible link between viral infection and obesity with a particular emphasis to the Adv36 will be reviewed."Thus, the Obesity Epidemic might be just that, an infectious epidemic.

In a study titled "Trim28 Haploinsufficiency Triggers Bi-stable Epigenetic Obesity", Andrew Pospisilik and team found that there are titillating hints that epigentics may play a role in determining who is fat and who is lean, even when they generally share the same genes (closely related individuals) , or in the case of identical twins, exactly the same genes.

No, the obesity epidemic is far from Hawking's, "Fortunately, the solution is simple." And the solution to obesity is orders of magnitude more complicated than "More physical activity and change in diet." In fact, universally reliable solutions to the problem of obesity do not yet exist.

There is nothing clearer from obesity research than that the simplistic policies of the federal health agencies and the learned societies - all of which were summarized by Stephen Hawking — "Eat Less & Exercise More" are totally inadequate to address the problem and are not based on scientific evidence. The "Eat Less & Exercise More" policies include the war on sugar and the war on soda - they cannot and will not make a clinically important difference in public health.

Summary:

- The kernel of truth in obesity studies is that consuming more calories (food energy) than one expends can lead to weight gain - energy stored as fat.

- Reversing this does not lead to a remedy for obesity - eating less and exercising more is not a cure for obesity.

- The reality of the problem of obesity is vastly more complex and only vaguely understood at this time.

- Current public policy on obesity is almost universally based on #1 above, ignoring #2 and #3. Thus, this public policy - no matter how strenuously enforced through education, indoctrination, regulation of the food industry, punitive taxation, etc will not resolve the Obesity Epidemic.

- On a positive note, the recommendation that people "eat less and exercise more" will not hurt anyone [with the rare exception of the profoundly underweight, the anorexic, etc] but, in general, will actually improve most people's health even though it may have no effect whatever on their weight status.

- The Obesity Wars share the common feature seen in other modern scientific controversies — public government agencies and scientific [and medical] associations forming a consensus behind a single solution, one known to be ineffective, to a complex problem - uniting in a broad effort to enforce the ineffective solution on the general public through regulations, laws, and mis-education.

Author's Comment Policy:

I have utilized only a tiny fraction of the information I have collected on this topic in the writing of this essay. Readers familiar with the literature on the topic will notice this immediately. This is not due to ignorance or laziness on my part - I have been constrained by the necessity of keeping the essay to a readable length, without unduly stretching the patience of you, my readers.

I realize that many readers here will want to move on immediately to discuss the Climate Wars - one of the distinctive science wars of our day. I ask that you please try to restrain yourselves

The last essay in the series will be an attempt to lay out a coherent pattern of modern science wars and maybe suggest ways that the different science fields themselves can break these patterns and return their specific area of science back to the standards and practices that should exist in all scientific endeavors.

# # # # #

Cultures who go through regular famines all get morbidly obese on a Western diet, and in many of those obese women are desired due to their being "healthy".

Maybe mother Nature is kick-starting the human race in the ass in preparation for a global fasmine.

Ya never know.