Juno arrived at the Jupiter system in July. On Aug. 27, the probe made a close flyby of the planet, during which, the science team was supposed to calibrate Juno's instruments and get familiar with the intense environment around Jupiter, according to Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton. But the encounter proved more fruitful than expected.

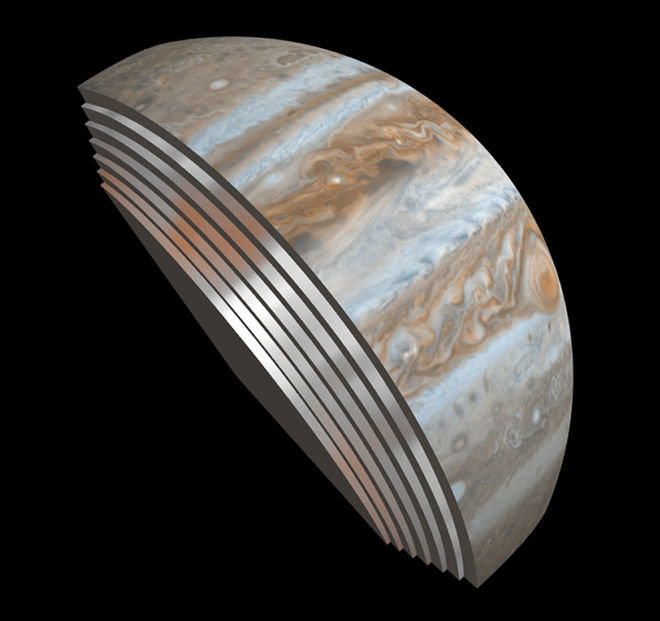

Jupiter's bold, colorful stripes are clouds, and optical light can't penetrate them to see what's underneath. However, Juno is carrying microwave instruments that can each probe those clouds to different depths; together, these instruments can effectively peel back the clouds like layers of an onion. An artist's impression based on the microwave data reveals a striking feature: Some of the stripes are visible deep into the cloud layers.

"The structure of the zones and belts still exists deep down," Bolton said during a news conference at the 2016 meeting of the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences. "So whatever's making those colors, whatever's making those stripes, is still existing pretty far down into Jupiter. That came as a surprise to many of the scientists. We didn't know if this was [just] skin-deep."

The new images penetrate to depths of about 200 to 250 miles (350 to 400 kilometers) below the surface cloud layer, Bolton said. He noted that the bands seen on the cloud tops are not identical to the bands seen in the subsequent layers, although there is clearly a strong similarity.

"They're evolving. They're not staying the same," Bolton said. The finding "hints [at] the deep dynamics and the chemistry of Jupiter's atmosphere. And this is the first time we've seen any giant planet atmosphere underneath its layers. So we're learning about atmospheric dynamics at a very basic level."

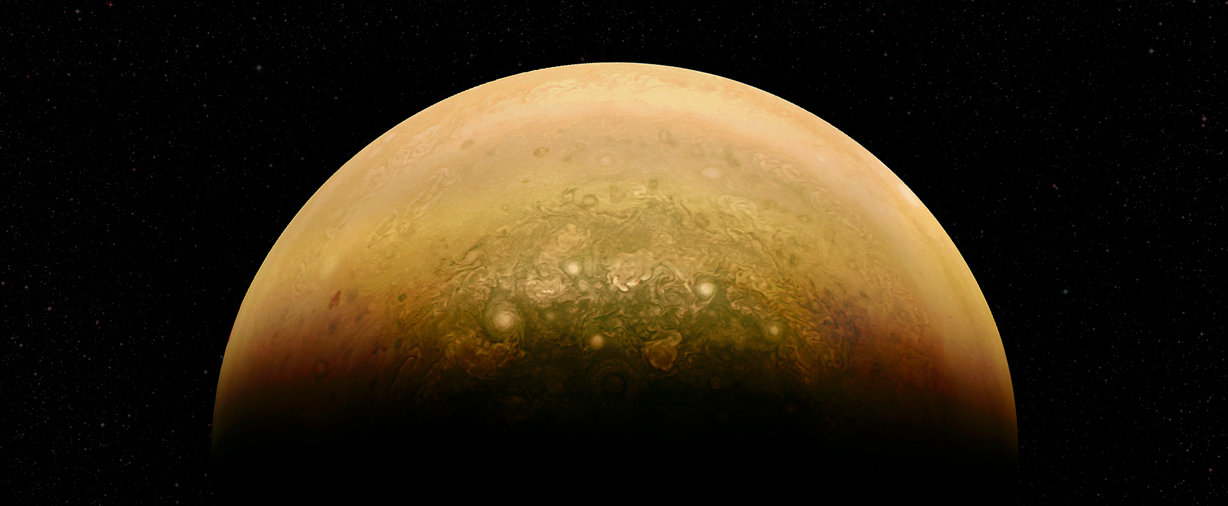

Another breathtaking result came from the JunoCam, a visible-light camera that is being used for public outreach. The instrument took a snapshot of Jupiter's terminator line, or the place where night turns to day. As is the case with viewing the moon's terminator line, the change in light casts shadows, allowing viewers to see many features in three dimensions (like being able to see the depth of craters on the moon).

In the Juno photo, scientists spotted a cyclone rising above the main atmospheric layer. The storm appears to be about 52 miles (85 km) tall and about 4,300 miles (7,000 km) wide, which is more than half the width of the Earth.

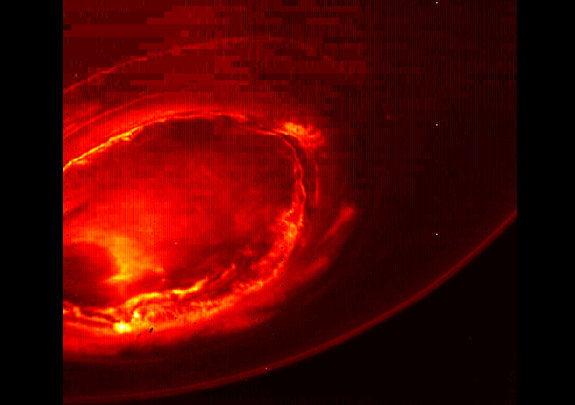

The auroras on Jupiter, which were first spotted by the Hubble Space Telescope, are not unlike the northern and southern lights that flash in the polar skies on Earth. But the data collected by Juno on Aug. 27 has thrown into question the models scientists had for Jupiter's auroras.

"Nothing about the aurora that we measured on Aug. 27 was as expected," Bolton said during a talk at the meeting. The probe flew over the auroras with multiple instruments turned on, but "the things we expected to see weren't there, and things we didn't expect were there.

"We're sort of sorting it out," Bolton said. "We've certainly got a mission of discovery [with regard to] the aurora and understanding that complex system."

In addition, measurements of the planet's magnetic field matched planetary models fairly well as Juno sped toward Jupiter. But in the last few minutes before the probe reached its closest point of approach to the planet, the data drastically diverged from the predictions, showing that the magnetic field was much stronger than expected, Bolton said. That implies that the internal magnetic field is "much more complex than people thought" he said.

But, of course, Bolton noted, no probe has ever come this close to Jupiter before, and the purpose of the Juno mission is to gather data that will put models like those to the test.

More surprises came from preliminary measurements of Jupiter's gravitational field (that is, the strength and direction of the planet's gravity at different points in space). Bolton said the Juno team members who made initial models of the planet's internal gravity field "are already having to redo the field model" based on those early measurements. "The internal gravity field also holds a lot of guarded secrets that are going to help us understand Jupiter," he said.

Juno's orbit around Jupiter isn't circular. Instead, the probe makes a loop that takes it right up next to the planet — to within 3,100 miles (5,000 km) of the cloud tops — and then far out into space, before looping back in for another close pass. Jupiter is surrounded by a donut-shaped ring of very intense radiation that could easily destroy most electronic equipment. Juno, with its unique orbit, does a thread-the-needle maneuver, slipping between the planet and the radiation ring.

Right now, Juno makes one orbit every 53 days. Juno was scheduled to fire its engines on Oct. 19 and reduce its orbit to every 14 days. Because of a problem with the engine valves, the Juno team has delayed that engine firing until the issue can be diagnosed. Juno is still able to complete its science mission if it stays in the 53-day orbit, Bolton said.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter