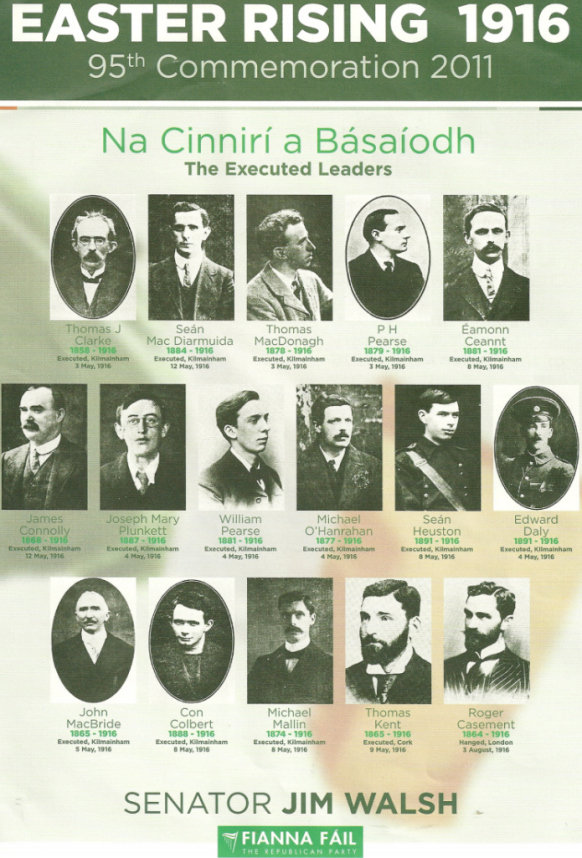

The Secret Elite and their imperial guard in the press, the foreign and the colonial offices, the war office and the great money houses in London and New York, made every effort to downplay the actions taken by James Connolly, Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, Sean Mac Diarmada, Eamonn Ceannt, Joseph Plunkett and the men and women who fought by their side. Because he represented an intellectual and dangerous challenge to the Empire, they promoted a devastating tirade against Roger Casement based on allegedly sexually explicit diaries which were circulated secretly to influence pro-Irish Americans.

Whatever the early success the anti-rebellion propaganda enjoyed, the rising was not a naive proposition to be dismissed by 'Empire Loyalists' as folly.3 Nor was it simply the sixth in line in a series of rebellions against British domination over the previous three hundred years. It was not an aberration or a theatrically staged protest. It was a statement of intent from a small minority group which refused to follow Redmond and Dillon blindly into a war they knew was wrong and which they deeply resented. And their numbers grew, slowly at first, as men and women who initially acted in good faith to support the Empire came to terms with the unpalatable fact that yet again the British government was using them as dupes.

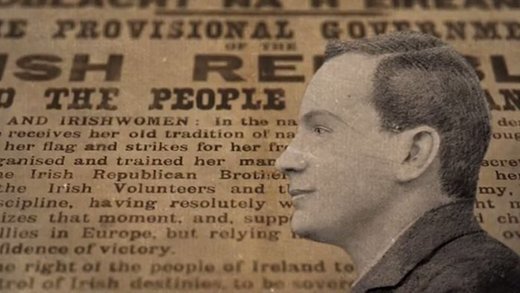

Though derided for their refusal to join the British army and labelled 'cowards', they were not. They saw the reality of the evil Empire ranged against Germany and refused to bend the knee. They were not to be fooled by false promises of Home Rule once the war was over. From an unforgiving courtroom Roger Casement caught the moment:

"We are told that if Irishmen go by the thousands to die not for Ireland, but for Flanders, for Belgium, for a patch of sand in Mesopotamia, or a rocky trench on the heights of Gallipoli, they were winning self-government for Ireland. But if they dare to lay down their lives on their native soil, if they dare to dream even that freedom can be won only at home by men resolved to fight for it there, then they are traitors to their country."4 Casement analysed it perfectly. The sacrifice of these men who joined up in 1914 did not win self-government for Ireland once the war had ended.

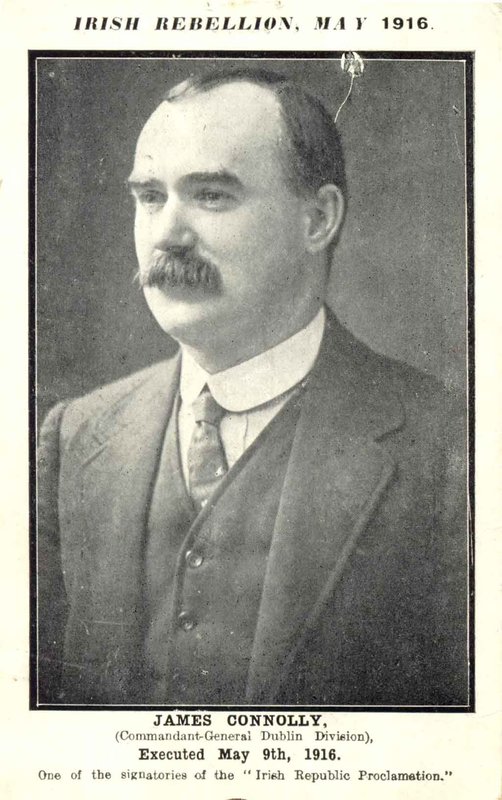

Just before he was executed, an unrepentant James Connolly wrote to his sister:

"We went out to break the connection between this country and the British Empire and to establish an Irish Republic. We believe that the call we thus issued to the people of Ireland was a nobler call in a holier cause than any call issued to them during this war."5Both men, and those who shared their conviction, acted not from narrow self-serving considerations but from a revulsion against Britain's declaration of war on Germany. They sought no association with the barbaric war. Theirs was an act of faith whose realisation they never saw. From it came a political reawakening, fuelled by the intransigence and arrogance of the Secret Elite. Casement, Connolly, Pearce and all who sacrificed themselves for Irish independence, were the spark that lit the flame.

It need not have come to that.

Had there been a genuine will to accommodate the aspirations of the Irish people, it would have been so different. Had the Secret Elite addressed the issue of Home Rule in Ireland with a more enlightened touch, the rebellion might never have had any impact at all. In stirring Ulster for their own purposes, the Secret Elite promoted an absolute determination in the Northern Province to detach itself from any Dublin-centred national government. As we have seen in previous blogs, their parliamentary agents in the Conservative party derided the advocates of Home Rule, wallowed in the overt injustices and inequalities between the different communities and armed and trained a private army to defend Ulster. Had the Secret Elite ordained that Asquith's coalition government, formed in December 1915, should acknowledge the great value of Ireland as part of the Empire's war effort, Irish citizens might have felt valued. Had the War Office listened to John Redmond and his pleas for the establishment of an Irish Army Corps, which Asquith endorsed in a speech in Dublin in September 1915, but failed to deliver, there would have been a greater sense of identity with the Empire's struggle.6 Such pious advocacy is empty talk for the men of real power, the money power, the financiers and policy -makers who acted behind the democratic front, the Secret Elite, had no intention of placating Ireland.

For the Secret Elite had caused the war, deliberately. Their purpose was to crush Germany and take control of the civilised world. They cared not a jot for the working people and the impoverished underclasses. They had no time to concern themselves about injustice in Ireland. And that is why the British establishment stuck to the mantra that Ireland could not be trusted. The irony was, it was they who could not be trusted.

Instead, the War Office engaged in"'a systematic suppression of recognition of the gallantry of the Irish troops at the front." Redmond stated in parliament that:

"I do not think that there was any single incident that did more harm to our efforts [to encourage enlistment] at that time than the suppression in the official dispatches of all recognition, even of the names being mentioned, of the gallantry of the Dublin Fusiliers and the Munster Fusiliers in the landing at V Beach at Gallipoli."7Such blatant discrimination by those in real power was indefensibly racist and counter-productive, but it represented their mind-set. Ordinary people did not matter and ordinary Irish men and women did not matter absolutely.

This suppression of national identity, this deliberate disassociation of a people with the valour and sacrifice of its fighting men because of their ethnicity and religion was a repression which rebounded and destroyed trust in Britain. How many historic prejudices were wrapped around the fact that "up to the time that the 16th went to the front, with the exception of two or three subalterns, there was not a Catholic officer in the Division."8 The final blow for many Irishmen in the South - and the biggest threat - came with the announcement of the coalition cabinet in December 1915. From that moment, recruitment to the British Army plummeted and support for the Irish Volunteers and independence, grew steadily. Home Rule was dead and buried, and a reborn Protestant ascendancy within the British government destroyed any lingering confidence in the impartiality of British rule.

The Secret Elite and their political agents believed that Ireland in 1916 was still a backward, ill-educated society, unable to comprehend what was happening all around its shores. Not so. People could clearly see that a Unionist executive had been installed in Dublin Castle, with a Unionist Chief-Secretary and a Unionist Attorney-General. These bitter opponents of Home Rule imposed a system of universal martial law encompassing hundreds of untried prisoners, many of whom did not even know the charges of which they were accused. The political system which had apparently agreed a great measure of home rule for Ireland in 1914, was transformed into a military dictatorship. The unelected minority were in charge. Again.

Everything the London government did was unjust. Everything the War Office ordered, threatened the identity of the Irish soldier. Whether it was meant as a punishment or determined through fear, injured and recuperating Irishmen at Boulogne were sent back to the front to serve in English divisions. It was estimated that there were twenty times more Irishmen in English, Scottish and Welsh battalions than there were Englishmen, Scots or Welshmen in Irish regiments. There was no justice. There was no equality. Redmond told parliament that he had received "scores and scores of letters" from Irishmen seeking transfer from their appointed regiment into the Connaught Rangers, but "never succeeded in a single case."10

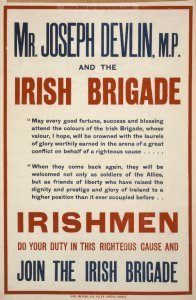

The malignant aggression of Secret Elite imperialist ambitions used every obstacle to prevent Irishmen from being credited for the successful prosecution of the war. After 1916, young Irishmen, suppressed by a Dublin executive severely out of touch with its own populace, preached a new gospel; one in which Home Rule representatives were no longer entitled to their support. Redmond, Dillon, 'wee' Joe Devlin and the Irish Parliamentary Party had failed. They had failed because they stood by a government which patently failed the people. Unable to grasp the truth that stared them down, the old order in Irish politics blamed 'prejudiced stupidity' inside the British government for the return to pre-1910 attitudes. No, it ran much deeper than mere prejudice. The guiding force behind both Asquith's and, later in 1916, Lloyd George's governments, unelected and full of place-men, was the Secret Elite, for whom Ireland was a mere side-show; an inconvenience which would be ironed-out in their good time. For the men and women of the Rising, an Irish Rubicon had been crossed.

The burning question is why John Redmond, and virtually all of the Home Rule (Irish Parliamentary) Party, continued to stay loyal to the Empire? Was it, as Shakespeare put it, that they were stepped in blood so far, that "returning was as tedious as to go'er"?11 They had never belonged to the political class of the Oxford Elite from whose staunchest ranks many in the Secret Elite were drawn. Redmond had been duped by the Asquiths into believing that loyalty to the Empire would be reflected in loyalty from the Imperial Parliament in London. He appeared to hold to the belief that in the end, even though time and again the Unionist-dominated cabinet thwarted his every good intention, he would be able to guide Ireland through the political turmoil. But his time had passed.

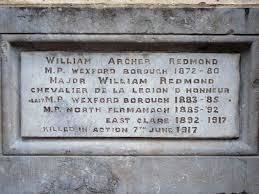

John Redmond continued to front parliamentary opposition to the British cabinet's designs on Ulster, although his political mandate became a thing of the past. His brother, 52-year-old Major Willie Redmond, MP for East Clare, was killed in action at Messines in June 1917, a hard blow for a parliamentarian who knew he stood on shifting sands. Major Redmond's parliamentary seat was taken by Eamonn de Valera, whose death sentence in 1916 had been remitted solely because he was an American citizen. De Valera was adopted as the Sinn Fein candidate in East Clare and won with an enormous 70 per cent share of the vote.12 John Redmond died broken-hearted in London on 6 March 1918.13

The tectonic plates of political confidence in Irish politics in the South clashed absolutely. The old order shook and fell. Like an avalanche, Sinn Fein, which had been but a doctrinaire idea held by a very small number in the community, developed a giant's strength. In the aftermath of the Easter Rising, Sinn Fein reaped a reward that many later claimed was undeserved. To be clear, Sinn Fein did not make the Rising, but the Rising made Sinn Fein.14 They held no association with Britain. They had consistently rejected war. The British press repeatedly accused 'Sinn Feiners' of plotting the Easter Rising as if it was a mark of infamy. This badge of dishonour in British eyes became the standard for the honourable rebel. Their ranks were swollen both by participants in the Rising and wrongfully deported sympathisers, freed from internment and prison in England. To paraphrase Yeats, in the aftermath of Easter 1916, "a terrible beauty was born."15

By 1918 Ireland was no longer the "one bright spot" which had lit up Sir Edward Grey's statement in 1914.16 It had been transformed into one of the most doubtful and difficult spots that ever coloured the Empire.17 Attempts by the British parliament to introduce conscription to Ireland later in the war only made matters worse. With 47% of the votes cast in the December 1918 General Election, Sinn Fein rose like a political colossus towering over Ireland. In 1910 they had no representatives; in 1918, they held 73 seats. The Irish Parliamentary (Home Rule) Party was destroyed. In 1910 it held 67 seats; in 1918, only six of their representatives were elected to Parliament.18

It was a disaster for the Secret Elite determination to bind Ireland to the Empire. In truth, their obduracy had blinded them to the consequences of democratic accountability. Much like the Scottish Labour Party in 2015, an inability to divest itself from association with an English party opened the way to a nationalist revival and cast the Irish Parliamentary Party into the political abyss. And this was the legacy of Patrick Pearse and the men who signed the Proclamation of 1916; a legacy predicated upon the Secret Elite's inability to accept that, in a changing world, republicanism in Ireland had replaced the softer notion of Home Rule under the British flag. They had tried, and continued to try, to repress an idea which had found its time.

Yet questions remain unanswered about the tumultuous events of Easter 1916. Given that the evidence we have previously presented proves without doubt that key members of the British establishment's most powerful political, naval and military decision-makers knew in advance that the uprising was scheduled, why was no action taken to forewarn Dublin Castle and the Irish Executive?

Given the fact that many documents pertaining to Easter 1916 remain classified, probably hidden amongst the thousands condemned to the government's secret repository at the high security communications centre at Hanslope Park in Buckinghamshire,19 has the time not come for outright honesty? What better gesture to continue the process of truth and reconciliation than the release of every single remaining document covering Easter 1916? The memory of all Irishmen who were sacrificed for the Empire and those killed during the uprising, and afterwards, deserves that truth.

Perhaps we are being overly idealistic. Sad to say, the old lies persist; old propaganda continues to populate the pages of contemporary newspapers in Ireland. Incredibly, an article in the Irish Times of 201420 began with this ridiculous statement: "The war began with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28th, 1914 and ended on Armistice Day, November 11th, 1918." Still the myth-peddlers stick to pro-war propaganda without a blush of shame. The First World War began on 4 August 1914 when the British Empire declared war on Germany. Prior to that, it was a European war involving France and Russia against Germany and Austria-Hungary. The conflict officially ended only after the Versailles Peace settlement was signed in 1919. Between November 1918 and June 1919, hundreds of thousands of German citizens were starved to death as the miserable food blockade continued unchecked. They apparently didn't matter then, so they won't matter now.

Bad though that is, we wonder why Ireland's leaders today stand, literally, shoulder-to-shoulder with their British counterparts at war centenary commemorations in solemn unquestioning agreement which perpetuates the great lie that tens of millions died for freedom and civilization. In doing so they tarnish not only the memory of all Irishmen killed or wounded in Europe and on Gallipoli, but the Irishmen who were branded cowards because they refused to take part.

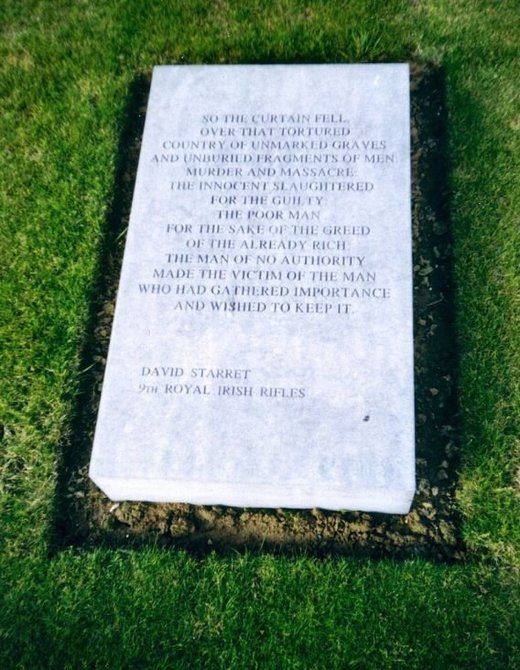

The memorable words of David Starret from the 9th Royal Irish Rifles have been carved in stone at the Irish Peace Park near Messines. He wrote home lamenting "the innocent slaughtered for the guilty, the poor man for the sake of the greed of the already rich, the man of no authority made victim of the man who gathered importance and wishes to keep it."

His poignant observation describes the Secret Elite in all their conceit.

The Irish government has to take more care lest its message implies that war was popular in Ireland and that those who stood against it acted dishonourably. They did not. Pearse, Connolly, Casement and all whom they urged into action, chose to sacrifice themselves for their country. As John Dorney pointed out "It is entirely appropriate for families and localities to remember their dead. But to suggest that the war for the Empire was popular in Ireland and only discredited by a malevolent plan by nationalists to 'airbrush it from history' is simply to twist the facts."21

How much more honourable to recognise that Ireland was committed to a war by politicians who believed that in the end Britain would reward the nation with Home Rule. In that, they were mightily deceived. Freedom is not a reward to be bestowed; it is a right that has to be fought for and defended. Thanks to those who sacrificed themselves for Ireland in 1916, Ireland in the 21st century is an independent nation.

They were the few.

Do not forget those who were sacrificed and those who sacrificed themselves.

Jim Macgregor: Co-author of Hidden History, Jim was born in Glasgow in 1947 and raised in a cottage in the grounds of Erskine Hospital for war disabled. He witnessed there the aftermath of war on a daily basis and, profoundly affected by what he saw, developed a life-long interest in war and the origins of global conflict. Leaving school at fifteen he worked in jobs as diverse as farm labourer, animal husbandry and medical research before graduating as a medical doctor in 1978. Jim left medical practice in 2001 to devote his energies full-time to researching the political failures in averting war. His numerous articles have been published on subjects such as miscarriages of justice, the Iraq War, global poverty, and the rise of fascism in the United States. His powerful anti-war novel The Iboga Visions was published to critical acclaim in 2009.

Gerry Docherty: Born in 1948, he graduated from Edinburgh University in 1971 and was a secondary school teacher by profession. He taught economics and modern studies, developed a keen interest in the theatre and has written a number of plays with a historical theme, including Czechmate in 1982, Montrose in 1993, and Lie of the Land in 2008. The last of these plays was the powerful story of two cousins from his home town of Tillicoultry who were both awarded the Victoria Cross at the Battle of Loos in 1915. Energised by the research he had undertaken to write this play, he was intrigued by Jim Macgregor's work on the First World War, and their mutual interest developed into a passion to discover the truth amongst the lies and deceptions that the official records contained.

Their ground-breaking book, Hidden History, The Secret Origins of the First World War, is available from Amazon. The above article is part of their ongoing research and writing on the hidden history of the First World War itself.

Notes

1. Patrick Pearse's proclamation can be viewed here.

2. W Philpott, Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the Making of the Twentieth Century, pp. 81-86.

3. Liam O'Ruaire, 'The Global-Historical Significance of the 1916 Rising'.

4. Sir Roger Casement, 'Speech From The Dock', from The Crime Against Europe with The Crime Against Ireland, introduced by Brendan Clifford, p. 167.

5. Michael Foy and Brian Barton, The Easter Rising, p. 355.

6. Hansard House of Commons Debate, 18 October 1916, vol. 86 cc581-696.

7. Ibid., cc586-7.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., cc587-8.

10. Ibid., cc593-4.

11. William Shakespeare, Macbeth, III. iv. 1136.

12. Fidelma McDonnell, 'Riches of Clare: 1917 Rising of an Irish Political Colossus'

13. Michael MacDonagh, The Life of William O'Brien, the Irish Nationalist, p.232.

14. Warrre B Wells, John Redmond; A Biography, p. 185.

15. W.B. Yeats, 'Easter 1916'.

16. Statement by Sir Edward Gray, HC Debate, 3 August 1914 vol 65 cc1809-32.

17. Matthew Keating, House of Commons Debate, 9 April 1918 vol 104 cc1412-13.

18. ark.ac.uk/elections

19. Ian Cobain, The Guardian, 18 October 2013.

20. Ronan McGreevy, The Irish Times, 2 January 2014.

21. theirishstory.com

I think the BIG battle for the Irish people is yet to peak. The darkness of catholicism. Vatican black magic, now diminishing, still controls the minds of many. Not just in Ireland but where ever it's filthy tentacles touch. Organized religion is the scourge of this world, and with the rise of the divine feminine, will be washed away. I am so very honored to witness these days.