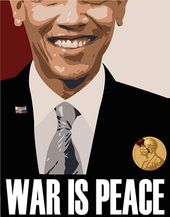

I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today - my own government.According to a recent global survey, the United States is perceived to be the greatest threat to world peace today. Its unrivalled war machine, out of control surveillance programme, decades-long record of attacking other nations, and its use of drones to carry out extrajudicial killings, lend credence to the charge that America is the world's number one war monger. It has not always been so. Before the Second World War the United States was reluctant to intervene militarily overseas, and no American troops were stationed in any foreign country.

Martin Luther King

World War Two changed all that. Within a few short years, the United States began the largest build up of arms in history and adopted a policy of armed intervention in the affairs of other nations. Psychopaths were largely responsible for these dramatic changes. This is the story of how psychopaths changed America.

Hitler and Hirohito

The first psychopaths to force a change in American policy were Hitler and Hirohito. When the Nazis invaded Poland in September 1939, and Britain and France declared war on Germany, the United States was reluctant to intervene. Even after the fall of France, when it was clear that Britain could not stand up to Hitler alone, the U.S. still refused to send American troops to Europe.

On December 7, 1941 Hirohito forced America's hand. Japan's attack on Pearl Harbour, and the Imperial Army's invasions of the Philippines, Malaya and Thailand, finally forced a reluctant America to enter the war.

But even before American troops joined the war, Hitler had already forced a far-reaching change in U.S. policy. On October 11, 1939, Albert Einstein met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to warn him that Germany was working on an atomic bomb. FDR responded by authorising the Manhattan Project and the development of the world's first atomic weapon.

Dilemmas in Europe and Asia

As the war progressed it brought about dramatic changes in the U.S. economy. By 1945 the U.S. was producing 45 percent of the world's arms and nearly 50 percent of the world's goods. While Europe, Russia and Japan were being devastated, America was rapidly becoming the world's strongest economy [1].

Despite its successes, however, the U.S. faced difficult dilemmas both in Europe and in Asia. In Europe, Hitler's attack on Russia, and the Russian counter-attack, threatened to bring Soviet forces right into the heart of Europe. FDR did not want Stalin to gain territory in Eastern Europe which he would be unlikely to relinquish when the war ended. But FDR also needed the Red Army to continue advancing beyond the borders of the Soviet Union. The stark reality was that the US and Britain could only defeat Hitler with the help of Stalin.

In Asia, American forces faced another challenge. Throughout the war there were never sufficient American ground troops to engage Japanese forces on the Asian mainland. Towards the end of the war, the US presence was limited to the Philippines and islands off Japan, while the Imperial Army, numbering many millions, retained control of much of China and most of South East Asia. America's newly tested atomic weapon offered a way to reverse the balance of power.

In Europe, the U.S. encouraged Stalin to advance into Eastern Europe. In Asia, the U.S. overcame its inferiority in ground forces by becoming the first, and so far only, nation to use the atom bomb.

Stalin

By war's end, the United States had been forced, by Hitler and Hirohito, into wars in Europe and Asia in which it did not wish to be involved. It had also developed and used nuclear weapons against civilian targets. Now it was the turn of another psychopath - Stalin - to move America even further away from its previous reluctance to wage war.

In Europe Stalin immediately began to impose brutal communist dictatorships on the countries he had occupied. The pitiless nature of Stalin's U.S.S.R., and the imposition of that system on Eastern Europe, meant that a clash between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. was inevitable. The U.S. was unwilling to accept that the war would simply result in the suppression of the peoples of Eastern Europe by Stalin, rather than by Hitler. The Cold War was at hand.

As the confrontation between the US and USSR escalated, the new President, Harry Truman, made a series of decisions that further redefined U.S. foreign policy.

In 1947, a crisis in Greece looked as if it might result in the seizure of the Greek government by communist forces backed by Stalin. Truman's response was decisive. Communist expansion, he believed, had to be stopped once and for all. In a speech to the House of Representatives, broadcast live to the nation, Truman declared, 'I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.' In practice this 'Truman Doctrine' meant that it was now U.S. policy to support of any foreign government, no matter how corrupt, against the threat of communism.

The following year, 1948, brought a communist coup in Czechoslovakia, orchestrated by Stalin. Unable to confront Stalin directly, Truman now authorised the newly formed U.S. Central Intelligence Agency to carry out covert operations abroad. The CIA was empowered to conduct political and economic warfare and paramilitary activities worldwide [2].

Then in September 1949, Russia tested its own atomic bomb. In response, Truman ordered the acceleration of the U.S. development of the hydrogen bomb. A nuclear arms race was underway. Overnight Europe had become the potential battlefield for a nuclear war of total annihilation.

McCarthy and Mao

The first few years of America's confrontation with Stalin set a series of perilous precedents. Covert intervention in the affairs of other nations was now official U.S. policy, and an uncontrolled nuclear arms race was under way. The use of paranoia and cheer-leading for freedom had also been established as tactics to secure the support of American people for this terrifying new reality.

It was now the turn of yet another psychopath, with the aid of paranoid Americans, to help the U.S. to extend its aggressive stance to Asia.

By 1949, Eastern Europe was lost to the Soviets and China had fallen to Mao. The climate was perfect for the rise of an anti-communist firebrand to further heighten the nation's paranoia. Senator Joseph McCarthy rose to the challenge. During the McCarthy era, beginning in 1950, thousands of Americans were accused of being communists or communist sympathizers and subjected to aggressive investigations by the FBI. Covert operations were now directed towards American citizens, as J.Edgar Hoover's FBI engaged in burglaries, opening mail and illegal wiretaps in its witch-hunt on communists. Many Americans lost their jobs without ever being told what they were accused of.

In this climate, no President could be seen to be weak on communism. Truman called for a review of American foreign policy to counteract the communist threat, which resulted in National Security Council policy paper NSC 68. NSC 68 called for an immediate and large scale build up of military strength. The US Department of Defence began to create an enormous armament industry producing thermonuclear weapons, families of atomic bombs, guided missiles, jet bombers, super-carriers, tanks, and countless other weaponry. America was developing a permanent war economy on a scale previously unimaginable and millions of American jobs and seats in Congress and the House of Representatives now depended on keeping it that way. The industrial-military complex was being created.

Then in 1950, Mao helped trigger the event Truman needed to extend America's policy of aggressive containment to Asia. In April 1950 Kim Il Sung met Mao to press for support for a North Korean attack on South Korea[3]. Mao responded by pledging support for Kim should the Americans enter the war. On June 25, North Korean forces invaded South Korea.

The following day Truman released a statement formally extending the Truman Doctrine to the Pacific, and pledged military intervention against any further communist expansion in the region. He extended military aid to the French fighting Ho Chi Minh in Indochina, extended the US security guarantee to Chiang Kai-Shek 's Taiwan, and committed US troops to the war in Korea.

Conclusion

In the space of a few short years, the US adopted the tactics of its enemies. It had intervened in support of corrupt governments abroad to further its own aims; it had engaged in paramilitary activities overseas, including intervening in the democratic processes of sovereign nations; it had adopted the use of paranoia and the propaganda of 'freedom' to gain the support of the American people; it had initiated a terrifying nuclear arms race; it had engaged in a programme of covert activities directed towards its own citizens; and it had commenced the construction of a military-industrial complex of a scale unimaginable just a few years before. It had done so largely in response to the actions of mass murderers overseas, abetted by the paranoia of some of its own.

Within five years of celebrating its victory in World War Two, psychopaths had changed America.

About the authorNotes

Ian Hughes has a PhD in atomic physics from Queen's University, Belfast, and has worked at some of the top research laboratories in Europe and the United States. On returning to government service in Ireland, he established a Department of Creative Technologies to explore the overlap between art and technology, and co-founded a programme to bring together scientists and journalists to make science more accessible to the public. He currently advises the Irish government in science, technology and innovation policy.

[1] Rise to Globalisation: American Foreign Policy Since 1938, Stephen E. Ambrose and Douglas G. Brinkley, Penguin Books, Ninth revised edition, 2011:27

[2] Rise to Globalisation: American Foreign Policy Since 1938, Stephen E. Ambrose and Douglas G. Brinkley, Penguin Books, Ninth revised edition, 2011:93

[3] Frank Dikotter, The Tragedy of Liberation: A history of the Chinese revolution 1945-57, Bloomsbury, 2013:129

It's time Americans drew their pockets out and faced up to the fact that's just not true….[Link]