Soon after Detroit emergency manager Kevyn D. Orr and Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder (R) approved a bankruptcy filing Thursday, groups representing the 20,000 retirees reliant on city pensions successfully petitioned a county court to effectively freeze the bankruptcy process.

Now, city and state officials, who say the court ruling will not affect their plans, are asking a federal judge to hold hearings early this week to validate the bankruptcy and move forward with a strategy for Detroit to discharge much of its estimated $19 billion debt.

Orr has promised that retired city workers, police officers and firefighters will not see pensions or health benefits reduced for at least six months. But on Sunday, he said those retirement benefits will have to be cut down the road.

"There are going to be some adjustments," Orr said on "Fox News Sunday." ". . . We don't have a choice."

"This is a question of necessity," he added.

But the prospect of cuts has sent a deep wave of fear over Detroit's retirees, who like many in the city are skeptical of Orr, a corporate lawyer who previously worked in the District, and Snyder, a Republican unpopular in this deeply Democratic city.

"It's been a nightmare for all of us," said Shirley Lightsey, president of the Detroit Retired City Employees Association. "We don't have that many people with pensions big enough for anything to be taken away from them."

Of Detroit's overall debt, about half - $9.2 billion - represents pension and health benefits that the city has promised retirees but that it now says it does not have enough money to fully pay. The lion's share of the remaining debt is owed to bondholders.

Orr has discussed a range of steps the city could take to pay off its debts, and some have speculated that they could include selling Detroit's international airport and valuable collections from the Detroit Institute of Arts. For current workers, he has proposed stopping pension contributions and shifting employees to individual retirement savings accounts.

But no part of the bankruptcy process is stirring as many passions as the potential need to slice pensions and benefits for retirees. Small cities that have filed for bankruptcy protection in recent years have significantly cut retirees' benefits.

Harry Harper, who lives in northeast Detroit and retired in 2003 from the city's Water and Sewerage Department after 30 years of service, said talk of benefit cuts is making him very anxious.

"I feel very vulnerable. I don't feel we have any protection," said Harper, 61, who receives $2,100 a month in pension payments. "I thought that at 30 years, you earned a pension that was accrued and you did not have to have a concern about that."

Retirees such as Harper say that living in Detroit on a fixed pension is tough since public transit has been cut back and fuel prices have been going up. Michigan's gasoline prices are among the highest in the country.

"I'm currently living check to check," Harper said. "Every time I get in my car, the first stop I'm making is at a gas station because of my cash flow." Jeanette Fitz, who retired after 35 years working in accounting for the city government, said she fears that a cut to her pension or medical coverage will be devastating.

Fitz said that she pays more than $100 a month for a half-dozen medications and that much of what remains from her pension payments goes toward her housing and other necessities.

"If they cut it, I'm not going to be able to pay my rent," she said. "I'm not going to have money. I'm going to be homeless. I'm going to be living out of my car, I guess."

On Sunday, Orr and Snyder said that they empathize with the fears of retirees but added that the city had ignored its problems for too long and that now there is no choice but to limit pension payments.

"You get honest about it to start with," Snyder said on NBC's "Meet the Press." ". . . In many cases for the last 60 years, people have ignored the realities of the situation. We're being real now."

Detroit Mayor Dave Bing said on ABC's "This Week With George Stephanopoulos" that one option not on the table is a federal bailout. "I think it's very difficult right now to ask directly for support," he said.

Technically, the dispute between the retirees and government leaders is about math - how to calculate how much of the pension system is not properly funded. But that is an unsettled area of accounting, and both sides are able to marshal expertise in their favor.

More fundamentally, though, the question facing Detroit is how much of its remaining financial resources it will use to repay bondholders who will be needed to lend money to the city in the future, to invest in the city's basic services and to hold fast to promises made to retirees.

"Ultimately, it's going to come down to a finite ability to pay," said Brian O'Keefe, a lawyer who represents retired city workers, police officers and firefighters. "We just simply believe that we must honor our obligation to pensioners who spent their entire lives working for the city."

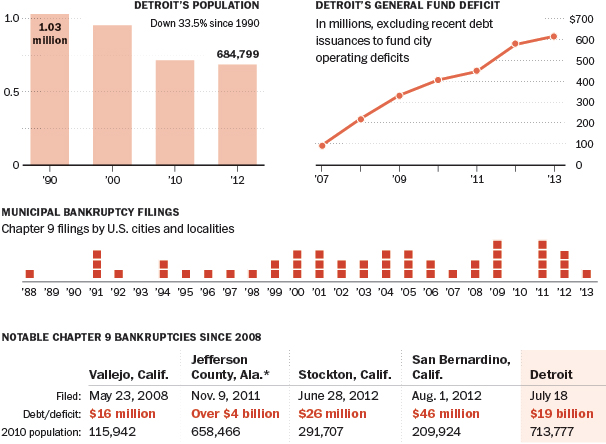

Detroit's financial and demographic decline will make that difficult, some experts note. The dramatic population slide the city has experienced over the past decade has hit municipal government hard.

In 2004, for instance, there was an even ratio of city workers to pensioners, but now there are six retirees for every four workers, according to a recent report by Orr.

Orr also has cast significant doubt on the calculations the pension systems have used to determine whether they have enough funding to meet obligations, noting that individuals involved in the pension system have recently faced criminal charges.

political machinations leading to this event. First, the passage of bill into law allowing the takeover of any municipality by de facto agent(s) of the governor and his cronies. Second, a skewed process for the examination and determination of fiscal liabilities of that municipality - with concomitant, "legally" justified dissolution of contract obligations of the municipality and their contractees at the discretion of the governor's appointed financial board of planners or planner. Third, a sale of publicly owned utilities, services and land meant to "strengthen" finances, followed by the inevitable declaration of bankruptcy due to the dissolution of all former revenue generating means (and, then, even more sales). All of this would be criminal if it weren't for the offending parties foresight lobbying for the passage of laws justifying it in the first place.

Next for the region: a new, international economic free trade development upon the public's Belle Island - something like the City of London meets the Detroit River.

Next for the rest of Michigan: resource grab through the same legislation. This will be principally low grade oil and gas in the Tittabawassee and Shiawassee River Valley, ground water from any "failing" municipality near any of the lake shores, and remaining coal, iron ore and copper in the upper peninsula. Detroit is to be the hub of the re-financialization of the region to come.