Scientists say the break, the largest on record since 2005, is the latest indication that climate change is forcing the drastic reshaping of the Arctic coastline, where 9,000 square kilometres of ice have been whittled down to less than 1,000 over the past century, and are only showing signs of decreasing further.

"Once you unleash this process by cracking the ice shelf in multiple spots, of course we're going to see this continuing," said Derek Mueller, a leading expert on the North who discovered the ice shelf's first major crack in 2002.

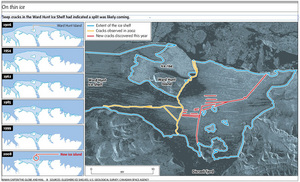

Dr. Mueller was part of a team monitoring ice along the northern coast of Ellesmere Island last April that discovered deep new cracks - 18 kilometres long and 40 metres wide - on the edge of Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, a 350-square-kilometre mass of ice that joins tiny Ward Hunt Island to the bigger Ellesmere. The cracks indicated a split was likely coming.

|

"It may weaken over time; it may melt away slowly, then all of a sudden you pass this threshold," Dr. Mueller said. "It's like a bar of soap. If you use the soap over and over again, it gets thinner and thinner. Then all of a sudden, it could break.

"Nobody knew when it would happen," he said, adding that specific conditions were required to enable it, including "offshore wind and a bit of open water in front of the ice shelf."

Sami Soja, a Kingston-based surveyor on contract to Parks Canada, was working on the island last week and was one of the first to witness the breakup.

"We hiked up [a peak] on the island, which is probably only about seven kilometres wide, ... and you could see those big cracks along it," he said, adding that, when he hiked back to the same point a few days later, "it was like, wow, something's totally different out there."

When Mr. Soja's team was airlifted off the island Sunday, they asked the pilot to fly over the ice mass so they could see the change from a better vantage point. From the air, he said, the group could see "a chunk was gone."

Trudy Wohlleben, a sea-ice forecaster with the Canadian Ice Service, said the chunk could float in the Beaufort Gyre, an ice-clogged, clockwise current in the Western Arctic, for some time and is unlikely to be an imminent danger to ships.

She and her colleagues are still working to establish what wind conditions were like when the ice broke away, but determining the time has proven tricky.

At this point, she said her team is confident the ice mass broke off last Wednesday or Thursday.

"There were southerly winds that pushed the sea ice offshore and probably helped break it off," she said.

"[Now] there's kind of an opening between the bulk of sea ice and the coast of Ellesmere. Last week that wasn't there."

Warwick Vincent, director of Laval University's Centre for Northern Studies, has had students monitoring conditions on the ice shelf for years.

He called the ice break "a significant event" that the shelf has been building toward since it began gradually thinning during the 1950s. Since then, over a 40-year period, the shelf thinned from 70 metres in the early 1950s to about 35 metres in the 1990s, Dr. Vincent said.

In 2002, when his then-student Dr. Mueller discovered that the shelf had cracked in two, continuing changes to the structural integrity of the shelf seemed inevitable.

"Over the last five years or so, there's been an acceleration of change in this area," Dr. Vincent said.

"We see this in a variety of indicators, including ... a gradual increase in air temperatures in this area. Each year it seems we're crossing a new threshold of environmental change in this area of the world."

Dr. Vincent said it's important to note that the Ward Hunt ice break is "small compared to what we've seen in the past."

Indeed, the largest ice break recorded in recent time was significantly larger: In 2005, the Ayles Ice Shelf, one of six in existence in Canada at the time, broke off in its entirety, rendering a 66-square-kilometre ice island that floated out to sea.

Still, the latest break "indicates ongoing change in this very sensitive area," Dr. Vincent said.

Dr. Mueller, whom Dr. Vincent calls the pre-eminent expert on Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, says he's concerned that the ice shelves will disappear completely.

"The take-home message for me is that these ice shelves are not regenerating," he said. "If we're looking at an indicator of whether climate is to blame, it's really the lack of regeneration that convinces me. They're breaking away so rapidly that there's no hope of regeneration," he said, adding that is "pretty strong evidence that suggests this is related to global warming."

The fall of the Disraeli Fjord

The first casualty of the fracturing of the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf occurred between 2000 and 2002, when the largest epishelf lake in the Northern Hemisphere, located in Disraeli fjord, drained into the Arctic Ocean through a giant crack in the ice.

Epishelf lakes are a rare ecosystem type that is particularly vulnerable to climate change. They are created when ice shelves completely block the mouth of a fjord. Fresh water that flows into the fjord every summer gets plugged behind the ice shelf and floats on top of the saltwater.

A metre-thick layer of ice on the surface of the fjord ensures the two layers of water don't mix. The distinct layers of water in the Disraeli fjord lake created an ecosystem that supported freshwater and saltwater versions of the same small animals, such as plankton.

Scientists believe the lake was created when the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf formed off the northern flank of Ellesmere Island around 3,000 years ago. According to images taken by Canada's Radarsat satellite, a massive fracture in the shelf occurred some time between 2000 and 2002, causing the epishelf lake to drain. By the summer of 2003, the lake had drained off the ice into the ocean, leaving no visible signs that it had ever been there.

The sudden draining of the lake through a giant crack produced a flood into the Arctic Ocean of no small consequence. Researchers at the time estimated the amount of water that drained was the equivalent of a month's worth of water from Niagara Falls, or around three billion cubic metres of fresh water.

"It was the loss of a rare ecosystem type," said Derek Mueller, a Trent University polar researcher. "We're losing features on the map and they're not returning."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter