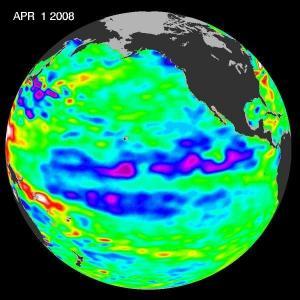

This La Niña, which has persisted for the past year, is indicated by the blue area in the center of the image along the equator. Blue indicates lower than normal sea level (cold water). The data were gathered in early April.

|

| ©NASA/JPL |

| This La Niña is indicated by the blue area in the center of the image along the equator. Blue indicates lower than normal sea level (cold water). |

The image also shows that this La Niña is occurring within the context of a larger climate event, the early stages of a cool phase of the basin-wide Pacific Decadal Oscillation. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation is a long-term fluctuation of the Pacific Ocean that waxes and wanes between cool and warm phases approximately every five to 20 years. In the cool phase, higher than normal sea-surface heights caused by warm water form a horseshoe pattern that connects the north, west and southern Pacific, with cool water in the middle. During most of the 1980s and 1990s, the Pacific was locked in the oscillation's warm phase, during which these warm and cool regions are reversed. For an explanation of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and its present state, see LINK.

A La Niña is essentially the opposite of an El Niño. During El Niño, trade winds weaken and warm water occupies the entire tropical Pacific Ocean. Heavy rains tied to the warm water move into the central Pacific Ocean and cause drought in Indonesia and Australia while altering the path of the atmospheric jet stream over North and South America. During La Niña, trade winds are stronger than normal. Cold water that usually sits along the coast of South America is pushed to the middle of the equatorial Pacific. A La Niña changes global weather patterns and is associated with less moisture in the air, and less rain along the coasts of North and South America.

"This multi-year Pacific Decadal Oscillation 'cool' trend can intensify La Niña or diminish El Niño impacts around the Pacific basin," said Bill Patzert, an oceanographer and climatologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. "The persistence of this large-scale pattern tells us there is much more than an isolated La Niña occurring in the Pacific Ocean."

Sea surface temperature satellite data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also clearly show a cool Pacific Decadal Oscillation pattern, as seen HERE. The shift in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, with its widespread Pacific Ocean temperature changes, will have significant implications for global climate. It can affect Pacific and Atlantic hurricane activity, droughts and flooding around the Pacific basin, marine ecosystems and global land temperature patterns.

"The comings and goings of El Niño, La Niña and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation are part of a longer, ongoing change in global climate," said Josh Willis, a JPL oceanographer and climate scientist. Sea level rise and global warming due to increases in greenhouse gases can be strongly affected by large natural climate phenomenon such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the El Nino-Southern Oscillation. "In fact," said Willis, "these natural climate phenomena can sometimes hide global warming caused by human activities. Or they can have the opposite effect of accentuating it."

Jason's follow-on mission, the Ocean Surface Topography Mission/Jason-2, is scheduled for launch this June and will extend to two decades the continuous data record of sea surface heights begun by Topex/Poseidon in 1992. JPL manages the U.S. portion of the Jason mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C.

For more information on NASA's ocean surface topography missions, see this LINK, or to view the latest Jason data, visit LINK.

Adapted from materials provided by NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter