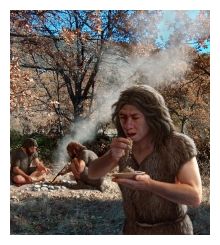

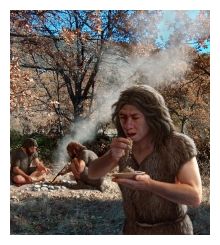

© Mauricio Anton/SPLNeanderthals were thought to eat only meat, but investigation of their dental plaque suggests they consumed cooked plants.

Neanderthals have long been viewed as meat-eaters. The vision of them as inflexible carnivores has even been used to suggest that they went extinct around 25,000 years ago as a result of food scarcity, whereas omnivorous humans were able to survive. But evidence is mounting that plants were important to Neanderthal diets - and now a study reveals that those plants were roasted, and may have been used medicinally.

The finding comes from the El Sidrón Cave in northern Spain, where the roughly 50,000-year-old skeletal remains of at least 13 Neanderthals (

Homo neanderthalensis) have been discovered. Many of these individuals had calcified layers of plaque on their teeth. Karen Hardy, an anthropologist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain, wondered whether it might be possible to use this plaque to take a closer look at the Neanderthal menu.

Using plaque to work out the diets of ancient animals is not entirely new, but Hardy has gone further by looking for organic compounds in the plaque. To do this she and a team including Stephen Buckley, an archaeological chemist at the University of York, UK, used gas chromatography and mass spectrometry to analyse the plaque collected from ten teeth belonging to five Neanderthal individuals from the cave.

The plaque contained a range of carbohydrates and starch granules, hinting that the Neanderthals had consumed a variety of plant species. By contrast, there were few lipids or proteins from meat.

Hardy and her colleagues also found, lurking in the plaque of a few specimens, a range of alkyl phenols, aromatic hydrocarbons and roasted starch granules that suggested that the Neanderthals had spent time in smoky areas and eaten cooked vegetables. The results are published today in

Naturwissenschaften1.

"The idea that Neanderthals were largely meat-eaters has been hard for me to accept given their membership in a mainly vegetarian clade. It is exciting to see this new set of techniques applied to understanding their palaeo-diet," says Richard Wrangham, an anthropologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Comment: Very interesting... it makes us wonder whether other so-called "tombs" were in fact meant for counting down the days the until the return of the "sky gods"...