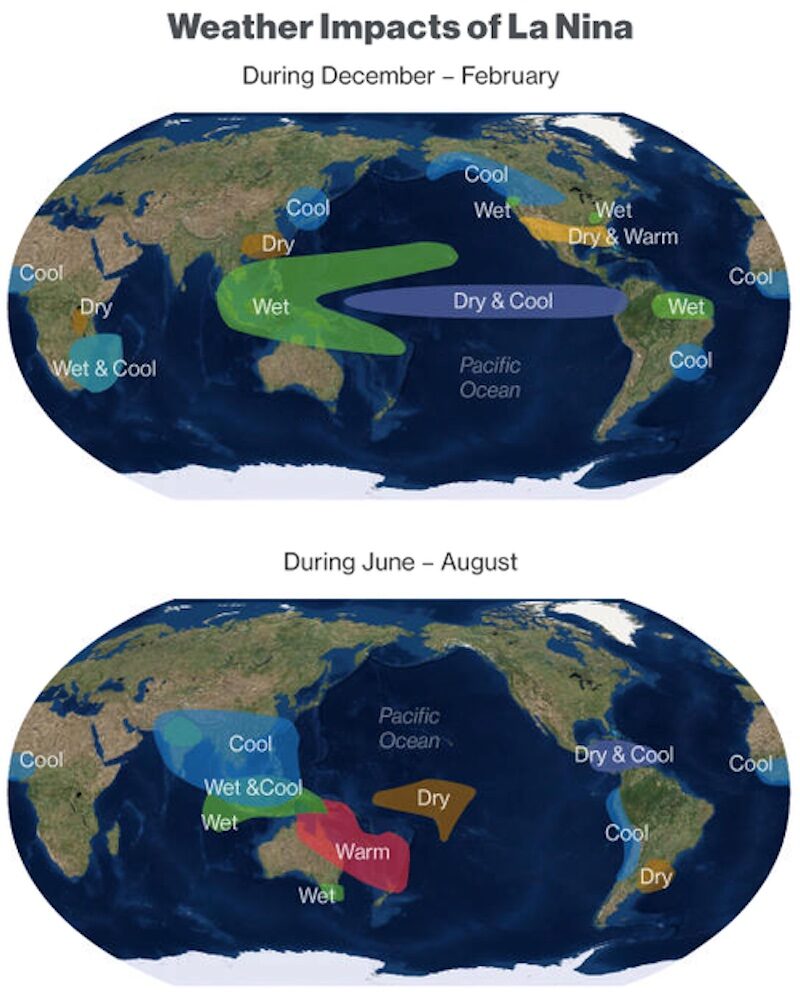

"It is exceptional to have three consecutive years with a la Nina event," World Meteorological Organization Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said in a statement.La Nina is expected to bring droughts to the US, South America, and eastern parts of Africa, while heavy rainfall in Australia, Indonesia, and other parts of Asia.

Bloomberg explains a "triple-dip" La Nina is very usual and what it could mean for weather trends ahead:

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, "El Nino and La Nina are naturally occurring climate patterns and humans have no direct ability to influence their onset, intensity or duration."How unusual is this?

Since 1950, according to US records, a La Nina in three consecutive years has occurred only twice, in the periods 1998-2001 and 1973-1976. As far as anyone knows there has never been a four-time La Nina, so forecasters believe the current one will fade in early 2023 after it peaks.

What could a third year of La Nina mean?

For California, the biggest farming state in the US, and for the soybean- and corn-growing areas of Argentina and Brazil, it could mean another year of drought. In Australia, it might bring another round of floods across Queensland, Victoria, and New South Wales, where rising waters produced at least $3 billion in insurance claims in early 2022. The price of a cup of coffee could climb if drought afflicts farmers in Brazil while floods hit those in Vietnam and Columbia. Sugar to sweeten it might also cost more if the cane used to make it gets stressed by a lack of rain. Across the Atlantic, there could be even more hurricanes than usual because there, La Nina cuts down on wind shear, one of nature's ways of putting a break on the destructive storms. In 2020, the Atlantic had a record 30 named storms, and in 2021 there were 21.

How does La Nina relate to El Nino?

La Nina is part of a bigger cycle known as El Nino-Southern Oscillation. ENSO, as scientists call it, is made up of El Nino -- so named by Peruvian fishermen for the Christ child in the 1600s when they noticed the tropical Pacific warming around Christmas some years, La Nina, and a neutral phase in between.

What causes this cycle?

El Ninos occur for reasons unknown, although some scientist think they are a way for Earth's atmosphere to shed heat into space. They begin with a weakening in the trade winds that push the sun-warmed waters of the equatorial Pacific into a mound in the west. Some of that water flows back east, making the eastern Pacific hotter. The phenomenon affects larger wind currents, shifting moisture-bearing storms away from some places, such as Indonesia and Africa, and toward others, including Argentina and Japan. When the heat from El Nino is spent, the ocean begins to cool. Initially, the Pacific falls into a state between the extremes, the neutral phase. If the cooling continues and sea surface temperatures fall below normal, La Nina occurs. The whole thing tends to play itself out every two to seven years. As has been evident since 2020, however, one end of the pattern can dominate for a time. The Atlantic and Indian oceans have similar events but theirs don't have the far-reaching impact of those in the immense Pacific.

So the deadly floods in Pakistan, heatwaves in the US Midwest, heavy rains in Australia and Indonesia, and a drought in Brazil and Argentina this year are likely La Nina-related and not as much climate change-related. Perhaps liberal elites know this and have shielded the truth from the masses as they push their green agenda under the guise that man is killing the planet.

Another year of La Nina will mean more extreme weather worldwide (and, of course, more angry tweets from climate alarmist Greta Thunberg). Bloomberg estimates La Nina related-damages could total nearly one trillion dollars in 2023.

Michael Pento, president and founder of Pento Portfolio Strategies, said La Nina "just exacerbates all the problems that already exist in the big picture, like the war in Ukraine and rising commodity prices."

"When you add in the extreme weather, it just creates a scenario for higher energy prices, higher food prices and more inflation. It's negative for the global economy, and it's working against the Federal Reserve," Pento said.Remember last weekend this UK physicist shocked an RT News anchor by saying: the climate "has always been changing, but this has nothing to do with man."

This shit quit making any sense a looooooong time ago.