This evidence was reviewed in detail by Jeffrey Anderson, a former director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics. He notes that:

of the 14 RCTs that have tested the effectiveness of masks in preventing the transmission of respiratory viruses, three suggest, but do not provide any statistically significant evidence in intention-to-treat analysis, that masks might be useful. The other eleven suggest that masks are either useless — whether compared with no masks or because they appear not to add to good hand hygiene alone — or actually counterproductive.In another piece that's well worth reading, Professor Steve Templeton provides a list of quotations from what he calls "the BP era" (Before Things Got Political). Each quotation, taken from one or other expert, testifies to the lack of evidence that community masking works against respiratory pathogens.

For example, in a systematic review published early last year, Jingyi Xiao and colleagues "did not find evidence that surgical-type face masks are effective in reducing laboratory-confirmed influenza transmission, either when worn by infected persons... or by persons in the general community to reduce their susceptibility".

This is presumably why, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, health authorities in both the U.K. and the U.S. advised against community masking.

For example, on 4th March 2020, Chris Whitty told Sky News that "wearing a mask if you don't have an infection reduces the risk almost not at all". And as late as 3rd April, Jonathan Van Tam said "there is no evidence that general wearing of face masks... affects the spread of the disease".

Likewise, in a tweet sent on 27th February, the CDC said that it "does not currently recommend the use of facemasks". And two days later, the U.S. Surgeon General urged people to "STOP BUYING MASKS" because they are "NOT effective" at preventing the general public from catching coronavirus.

In a video interview from May of 2019, Anthony Fauci actually laughed at the notion of wearing a face mask. The interviewer asks him, "The best way for me to prevent getting an infectious disease... is what? Wearing a mask?" To which Fauci replies, "No, no no... you avoid all the paranoid aspects."

Yet by the summer of 2020, the health authorities in both countries had done an about-face, and were now recommending face masks to the public. These recommendations subsequently became mandates.

'The Science,' in other words, had changed. But what prompted this change? The charitable answer is that new evidence emerged suggesting that community masking does work against SARS-CoV-2. However, this new evidence looks just as shaky - if not shakier - than the pre-Covid evidence.

I suspect that something else happened. Back in the spring of 2020, all Western countries were on the same upward trajectory, with cases doubling every few days. Meanwhile, Japan, Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore had all manged to 'flatten the curve', despite eschewing draconian lockdowns.

Commentators were searching around for an explanation, and 'masks' seemed like a good one. After all, Western health authorities had advised against masks. Yet many East Asians had been wearing them for years.

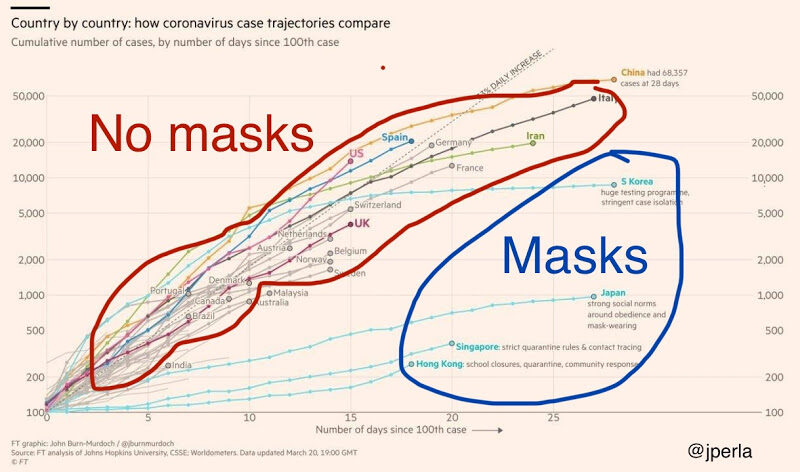

If you were on social media at that time, you probably remember seeing a version of this chart, which went viral numerous times:

Putting 'correlation doesn't equal causation' aside, it appears to suggest that masks are the crucial factor for bringing COVID under control. Of course, the subsequent imposition of mask mandates in Western countries didn't forestall large winter outbreaks, which rather undermines the mask theory.

Nonetheless, it seemed plausible enough at the time. And articles began appearing in major news outlets that questioned the West's reluctance to wear face masks. On social media, commentators asked why we shouldn't follow the East Asian countries, given their far greater success in handling the pandemic.

I suspect this pressure had more to do with the health authorities' about-face than any fundamental change in the quality of evidence. It was another case of 'politician's logic'. 'Something must be done; mask-wearing is something; therefore we must do it.'

In a matter of weeks, 'The science' went from 'don't do X' to 'do X'. And yet it took another whole year for the first RCT of community masking to be published. The theory I've outlined is speculative, of course. But I don't see what else can account for such a sudden shift in public health advice.

Comment: See also: