According to new research published today (Jan. 7) in the journal Nature, the girdled constellation may also be a small piece of the single largest structure ever detected in the Milky Way galaxy — a swooping stream of gas and baby stars that astronomers have dubbed "the Radcliffe Wave."

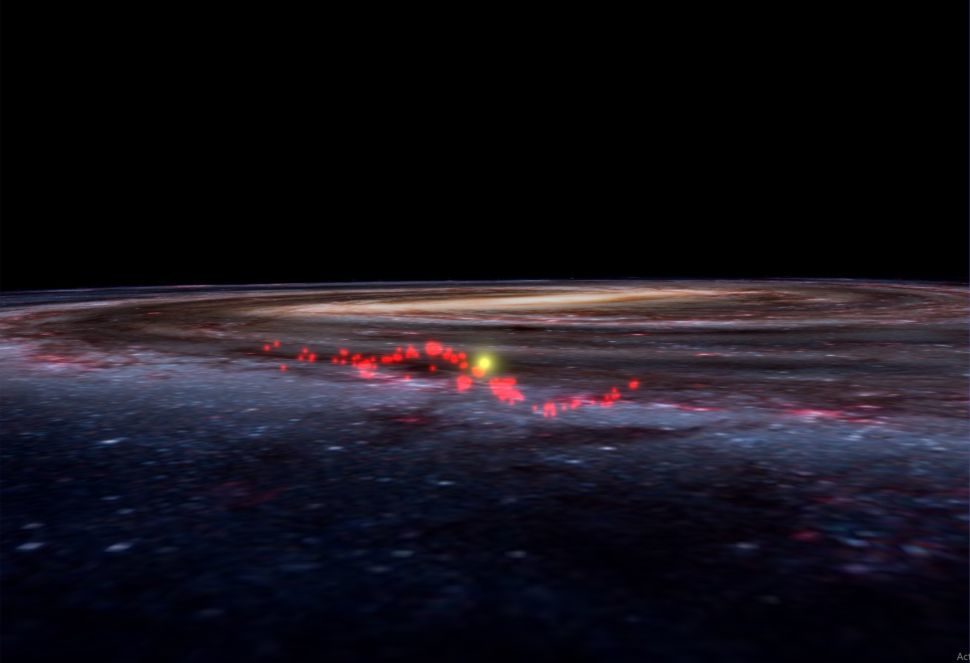

Spanning about 9,000 light-years (or about 9% of the galaxy's diameter), the unbroken wave of stars begins near Orion in a trough about 500 light-years below the Milky Way's disk. The wave swoops upward through the constellations of Taurus and Perseus, then finally crests near the constellation Cepheus, 500 light-years above the galaxy's middle. The entire undulating structure also stretches about 400 light-years deep, includes some 800 million stars and is dense with active star-forming gas (known in more delightful terms as "stellar nurseries").

When observed in 3D atop the rest of the Milky Way, this swooping suburb of baby-booming stars appears to be more than just the sum of its parts, study co-author João Alves said in a statement.

"What we've observed is the largest coherent gas structure we know of in the galaxy," said Alves, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Vienna. "The sun lies only 500 light-years from the wave at its closest point. It's been right in front of our eyes all the time, but we couldn't see it until now."

Alves and an international team of colleagues detected the Radcliffe Wave (named for Harvard's Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, where the bulk of the research was conducted) while creating a 3D map of the Milky Way with data gathered largely by the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite. They noticed the strange, undulating pattern of gas and stars around Orion when looking at an object known as the Gould Belt, which was first detected more than 100 years ago.

For a century, astronomers have thought the Gould Belt was a ring-shaped circle of star-forming gas, with Earth's sun near its center. However, once the authors of the new study began digging into the Gaia data, they realized this does not seem to be the case. Rather, the Gould Belt appears to be just a piece of the much larger Radcliffe Wave, which does not form a ring around our solar system but swoops toward and away from it in an enormous waveform.

"We don't know what causes this shape but it could be like a ripple in a pond, as if something extraordinarily massive landed in our galaxy," Alves said.

Prior studies of the Gould Belt have suggested the same. Perhaps a gigantic blob of dark matter crashed into the young gas cloud millions of years ago, warping the galaxy's gravity and scattering the nearest stars into the pattern seen today, one 2009 study in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society posited.

"What we do know is that our sun interacts with this structure," Alves said.

According to the researchers, stellar velocity data suggests that our solar system passed through the Radcliffe Wave some 13 million years ago — and, in about another 13 million years, will cross into it again.

Comment: See also: Betelgeuse is "fainting" but it's not about to go supernova - probably

The school associated with this paper recently released a lecture entitled The Rise of the Milky Way which, according to the blurb "explains how an exhibition by the artist Anna Von Mertens helped guide him to the "Radcliffe wave":