In an extraordinary moment captured on film this summer, the tuning pegs and neck of a lyre, a harplike stringed instrument, were carefully prised out of the soil of Ribe, a picturesque town on Denmark's south-west coast. Dated to around AD720, the find was the earliest evidence not just of Viking music, but of a culture that supported instrument-makers and musicians.

The same excavation also found the remains of wooden homes; moulds for fashioning ornaments from gold, silver and brass; intricate combs made from reindeer antlers (the Viking equivalent of ivory); and amber jewellery dating to the early 700s.

Even more extraordinary, however, was the discovery that these artefacts were not for home consumption by farmers, let alone itinerant raiders. Instead, the Vikings who made them lived in a settled, urban community of craftsmen, seafarers, tradesmen and, it seems, musicians.

"Ribe confounds history," says Richard Hodges, a British archaeologist and the president of the American University of Rome. "What we have here defies the opinion that all the Vikings did was to raid and to rape."

The discoveries at Ribe suggest mass production, high levels of specialisation and a division of labour - all characteristics of a settled urban society rather than a nomadic one based on pillaging.

"We can see in Ribe that Viking society was based on sophisticated production and trade," Hodges says. "It is a paradox: they made these beautiful things, they had gorgeous cloth, wonderful artefacts, but at the same time they are known to history for their brutality."

European history has been written from the perspective of Christian chroniclers who wanted to tell us that Vikings were barbarians, Hodges notes.

Speeding through the autumn countryside on one of his frequent journeys to Ribe, Søren Sindbæk, an archaeologist from Aarhus University, keeps up a constant stream of thoughts about the site's broader historical significance.

"A transformation took place in northern Europe between the end of the Roman period - when this was the dark side of the continent - and the Middle Ages, when it became a bustling region with great cities, cathedrals and commercial shipping," says Sindbæk.

"That change, leading eventually to the European age of exploration and world trade hegemony, begins here on the North Sea coast, where urban Vikings were a catalyst."

Another find is a tiny silver coin the size of a fingernail, preserved so well it could have been minted yesterday. Coinage is evidence of a stable trading community, says Morten Søvsø, chief archaeologist.

Ribe has long been known as an early trading settlement. The question posed by the latest discoveries is about the relationship between these urban Vikings and the period of raids that followed the attack on Lindisfarne - Britain's 9/11 moment, as Sindbæk puts it.

"The fact we can see this trading system was already in place before the Viking raids started in the British Isles makes it likely that the two things have something in common," he says, adjusting the broad-brimmed Indiana Jones hat he keeps in the boot of his car for rainy days.

"It could be that the raids were actually the tip of an iceberg of trade - there is evidence of a trading relationship with Scandinavia, but we haven't heard about the peaceful side."

The site in Ribe is unique because it enables precise dating of the finds, thanks to deposits that have lain undisturbed in the sandy, worm-free soil. Lasers have been scanning the site as each layer of history is peeled away, creating a 3D model of the eighth century so samples can be precisely located in the archaeological record.

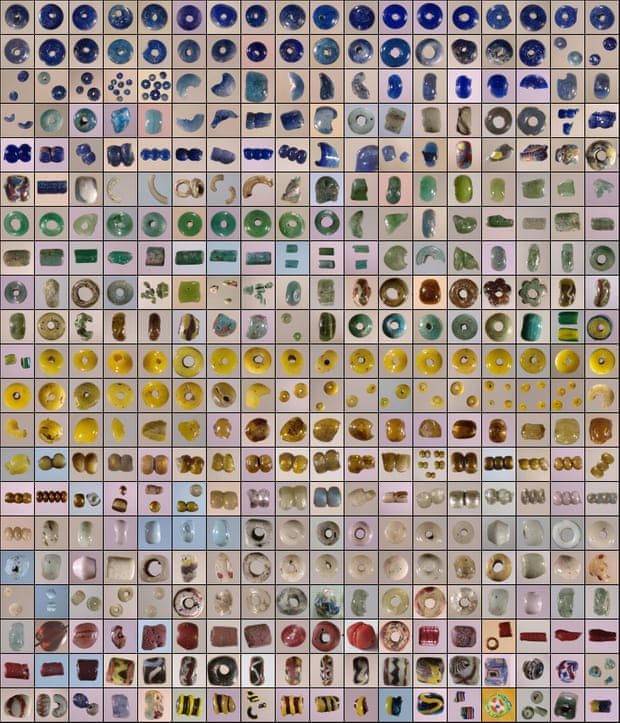

This method has revealed that the bead-makers of Viking Ribe were early victims of globalisation. Mass-produced beads from towns such as Raqqa in present-day Syria started arriving in bulk around AD780, undercutting the local trade.

The Danish archaeologists have applied another technique for squeezing every last drop of knowledge out of the site at Ribe. Blocks of soil no larger than a cigarette packet are impregnated with resin so they can be sliced into thin sections, which can then be analysed under a microscope.

The dig, funded by the Carlsberg Foundation and carried out by Aarhus University with the Museum of Southwest Jutland, began in 2017 and is now complete; the 100 sq metre site has returned to public use. Many discoveries lie ahead, Sindbæk says, as he and his colleagues study the data and materials they have assembled.

A few days earlier, she says, she plucked a perfect tiny amulet from the muddy soup, marked with a Christian cross - a "huge adrenaline rush" - suggesting Christian currents were present here long before King Harald Bluetooth's declaration on the Jelling runestone circa AD965 that he had brought the religion to the Danes.

"Some written sources have presented the Vikings as barbarians in order to make themselves look good," Hee says. "So we cannot completely trust people writing at the time: are they describing what they saw or imposing their own understanding on it?"

Archaeologists uncover a Viking musical instrument from Ribe, the site of an early Viking city.

Comment: Evidently what we've been told about the Viking's is far from the truth, and it's likely they're used as cover by chroniclers to explain the disaster which befell Briton and nigh on wiped out the population.

As Laura Knight-Jadczyk in Meteorites, Asteroids, and Comets: Damages, Disasters, Injuries, Deaths, and Very Close Calls writes: And the Vikings were likely beneficiaries of the warm period that followed: See also: