Landing in London, "MBS" might have dispensed with his chauffeur-driven car, travelling into the capital by Uber, while his aides finalised his itinerary on smartphones powered with chips designed by Cambridge-based ARM Holdings. After glad-handing bank chiefs in the City, any investment plans they discussed could have been further developed using cloud office app Slack.

On the US leg of the journey, perhaps slumming it in an Accor hotel, MBS and his entourage might have dialled up a plate of the Saudi national rice dish, kabsa, from delivery service DoorDash. Later, they could have relaxed by playing computer games partly designed by simulation technology firm Improbable.

Every one of these companies is part of the portfolio of Riyadh's Public Investment Fund (PIF), which manages the country's oil wealth. Under the stewardship of the young prince - he is just 33 - the PIF has adopted a more aggressive investment approach, seeking out eye-catching, forward-looking deals, particularly technology startups. Its aim is to increase the pot from $250bn to $2 trillion in the next 12 years.

This strategy is a key part of Vision 2030, a blueprint to reduce Saudi reliance on oil and diversify the economy into sustainable industries with a long-term future. But the plan hasn't gone smoothly.

"The idea is that you give the money to the PIF and they invest seriously all over the world, particularly in hi-tech and future-oriented industries," says David Butter, Middle East and north Africa analyst at Chatham House.

"But a sovereign wealth fund is by definition based on surplus revenue and Saudi Arabia has been running deficits because the oil price is weak, so they need to get [the money] from somewhere else."

Butter points out that Riyadh hoped to accelerate its plans by raising $100bn from the flotation of a 5% stake in its giant state oil company, Aramco, an offering since put on hold.

But even if funds can be raised elsewhere, the international investment component of the masterplan is at risk, due to the allegations - denied by the crown prince - that he ordered the murder and dismemberment of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

The keystone of the international strategy - which could now be under threat - has been the kingdom's provision of nearly half the money in the $93bn Vision Fund managed by Japan's Softbank. Much of that cash has gone into potential future blue-chips such as Uber, electric car start-up Lucid Motors and General Motors's driverless car unit, GM Cruise.

MBS is close to Softbank's billionaire chief executive, Masayoshi Son, one of the few business leaders not to have pulled out of next week's Future Investment Initiative (FII) in Riyadh - described as "Davos in the desert" - in light of the allegations. But the gruesome scandal does appear to have tested even that close relationship.

Earlier this month, MBS told Bloomberg that the PIF was ready to pump another $45bn into a second Vision Fund. By the end of last week, Softbank appeared to have cooled on the idea, with its chief operating officer, Marcelo Claure, saying there was "no certainty" such a fund was in the offing.

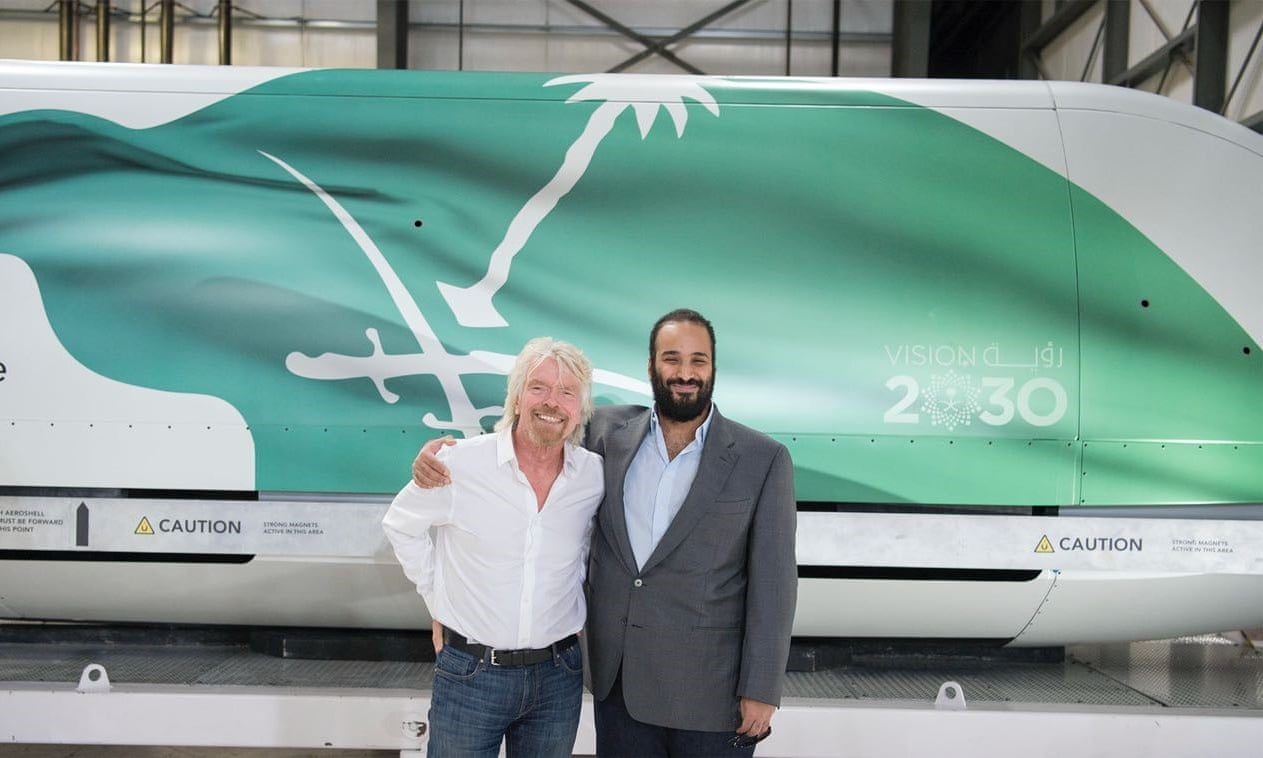

The high-profile pull-outs from the FII include JP Morgan's Jamie Dimon, the head of the IMF, Christine Lagarde, Glencore chairman Tony Hayward and many more - even Uber's boss, Dara Khosrowshahi, despite the PIF's $3.5bn investment in his company. Separately, Richard Branson has suspended the Gulf state's $1bn investment in his space project, Virgin Galactic. Rarely have so many business leaders been seen running in the same direction, in this case away from Saudi Arabia at speed.

All of this deals considerable damage to the public profile of a man who was meant to be the standard-bearer for reform and modernisation. When MBS was in California on his tour, he hired out most of the Four Seasons hotel in Beverly Hills, enjoying lunches with Rupert Murdoch, rubbing shoulders in Silicon Valley with the likes of Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg and schmoozing film stars.

"The persona he was trying to put out there was that he's one of them, these business moguls. It was clear that rubbing shoulders with all of these big names was something he enjoyed," says Butter.

"There's definitely a prestige goal and they've been explicit about that," says Rachel Ziemba, adjunct senior fellow at the Centre for a New American Security thinktank. "There's a desire to be an economic powerhouse and an effort to invest in state-of-the art technologies that they hope to use in Saudi Arabia, but which also put them on the front page of the newspaper."

Even more crucial than prestige are the economic ramifications, and not just when it comes to boosting investment returns from the PIF. Every overseas deal brings with it international connections that contribute towards realising the domestic Vision 2030 plans.

These include massive expansion into solar power, cultural and technological development, not to mention the so-called giga-projects, such as the construction of islands in a tourism complex along the Red Sea coast and a futuristic new city, known as Neom, in the country's far north-west.

Achieving these goals requires expertise that the kingdom doesn't necessarily have, cannot develop quickly and must import instead.

The document was full of mutual praise. The UK recognised "the substantial potential for Saudi Arabia as a global investment powerhouse", while the Saudis recognised London's "unrivalled" place as a financial centre, a position the capital promptly lost to New York shortly afterwards.

But the core of the agreement was for "mutual investment opportunities" worth $100bn over 10 years, including $30bn in direct investments in the UK from the PIF. In exchange, the UK is to share expertise in clean energy, electric vehicles, financial services, culture and entertainment, healthcare, life sciences and, of course, defence.

Any and all of these partnerships are likely to involve businesses which, right now at least, fear Saudi is toxic.

"There's a line between not going to a public event [the FII] and what happens with actual cash placements," says Ziemba. "But for some investors, this is another example of uncertainty around Saudi foreign policy.

"They may have more challenges attracting inward investment than placing it abroad with companies that usually need the money."

Nigel Kushner, chief executive of W Legal and an expert in sanctions, warns that the worst-case scenario for the Saudis is if the US decides to put individuals and businesses on the list of those sanctioned under its Magnitsky Act.

"The reality is that business internationally would be closed for anyone on the list," says Kushner. "If they put business people or companies on the list that would have a meaningful impact: it could all be removed overnight if the US were minded to do so. But I very much doubt it will be."

A wide portfolio

The vast oil wealth of Saudi Arabia and its royal family has been spread liberally around the world in recent years. Many of their overseas assets are owned via the mammoth $93bn Vision Fund shared with Japan's Softbank, while some are personal playthings of sundry royals.

These are some of the assets, ranging from steel to Silicon Valley.

The Vision Fund

Saudi Arabia put up $45bn of the $93bn in the Vision Fund, the world's largest private equity pot, managed by Softbank. The investment vehicle has poured cash into more than 25 companies, particularly tech startups and champions such as Uber - the Vision Fund is the ride-hailing app's single biggest shareholder with a $9bn stake. Saudi Arabia's sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF), separately owns 5%, worth $3.5bn.

ARM Holdings is the second biggest investment in the Vision Fund stable. The Cambridge-based tech firm designs chips used in millions of smartphones around the world. The Vision Fund has a 25% stake worth $8.3bn, as well as $8.2bn in fellow chipmaker Nvidia.

It has also ploughed $2.3bn into GM Cruise, the driverless cars unit of General Motors, and $4.4bn into workspace company WeWork.

London-based startup Improbable, which creates virtual worlds for video games, attracted $500m from Softbank, which later moved it into the Vision Fund.

Slack, perhaps best described as a Facebook for business, is a cloud-based virtual office that won a $300m injection. Other Vision Fund investments include food delivery service DoorDash ($500m), German online car dealer Auto1 ($460m) and biopharma firm Roivant ($1bn).

Blackstone infrastructure

During President Trump's visit to Saudi last year, it was announced that the PIF would plough $20bn into a $40bn US infrastructure fund managed by investment giant Blackstone. The project is in its early stages and has struggled to find appropriate investments.

Other investments

The PIF has also sought out tech projects beyond the Vision ambit and owns a 5% stake in electric car maker Tesla. It also joined big-name backers to invest in secretive augmented reality startup Magic Leap, backing it with $400m. It also holds interests in steel, via a subsidiary of ArcelorMittal.

Personal investments

Some Saudi royals are big investors in their own right. Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal spent $25m on a 2.3% stake in Snapchat this year, plus $267m on shares in French music streaming service Deezer. He already owns stakes in Twitter and ride-hailing service Lyft.

Then there are the usual personal fripperies, such as Mohammed bin Salman's $300m French chateau and a yacht that cost even more, at $500m. But they hardly seem worth mentioning.

Comment: See also: