It would hardly be an exaggeration to note that Russian state and media figures have, in a figurative sense, danced on the grave of a U.S. lawmaker whose latter years in politics were marked by an abiding hatred of all things associated with the Kremlin, and a deep commitment to expanding NATO across the post-Soviet space.

"The main Russophobe of America" was one appellation given to the right-wing Arizona lawmaker in an obituary carried by state-run news agency RIA NOVOSTI, which noted:

Perhaps McCain was a patriot of America, and perhaps even a hero; but Russia remained a mystery to him. He did not understand [it.]"Russian legislator and Chairman of the Federation Council Alexei Pushkov cited McCain's own words to mock the late senator's efforts to effect regime change in the Syrian Arab Republic through the ouster of President Bashar al-Assad and backing of Islamist militants. He wrote:

'Gaddafi is on the way out, next in line with Bashar Assad,' John McCain said seven years ago, in August 2011. The overthrow and death of Assad did not happen on the watch of McCain. Politics and fate decided otherwise. McCain's plans to restructure the world under the total hegemony of the United States have not come true."Senator Oleg Morozov of the Federation Council's Foreign Affairs Committee offered his own back-handed honors, noting that McCain "was good in his hatred toward Russia. He was the symbol of contemporary overt anti-Russian thinking."

"Give him credit for his honest enmity, hatred and intransigence. Others play a double game. He said what he thought," he added, concluding:

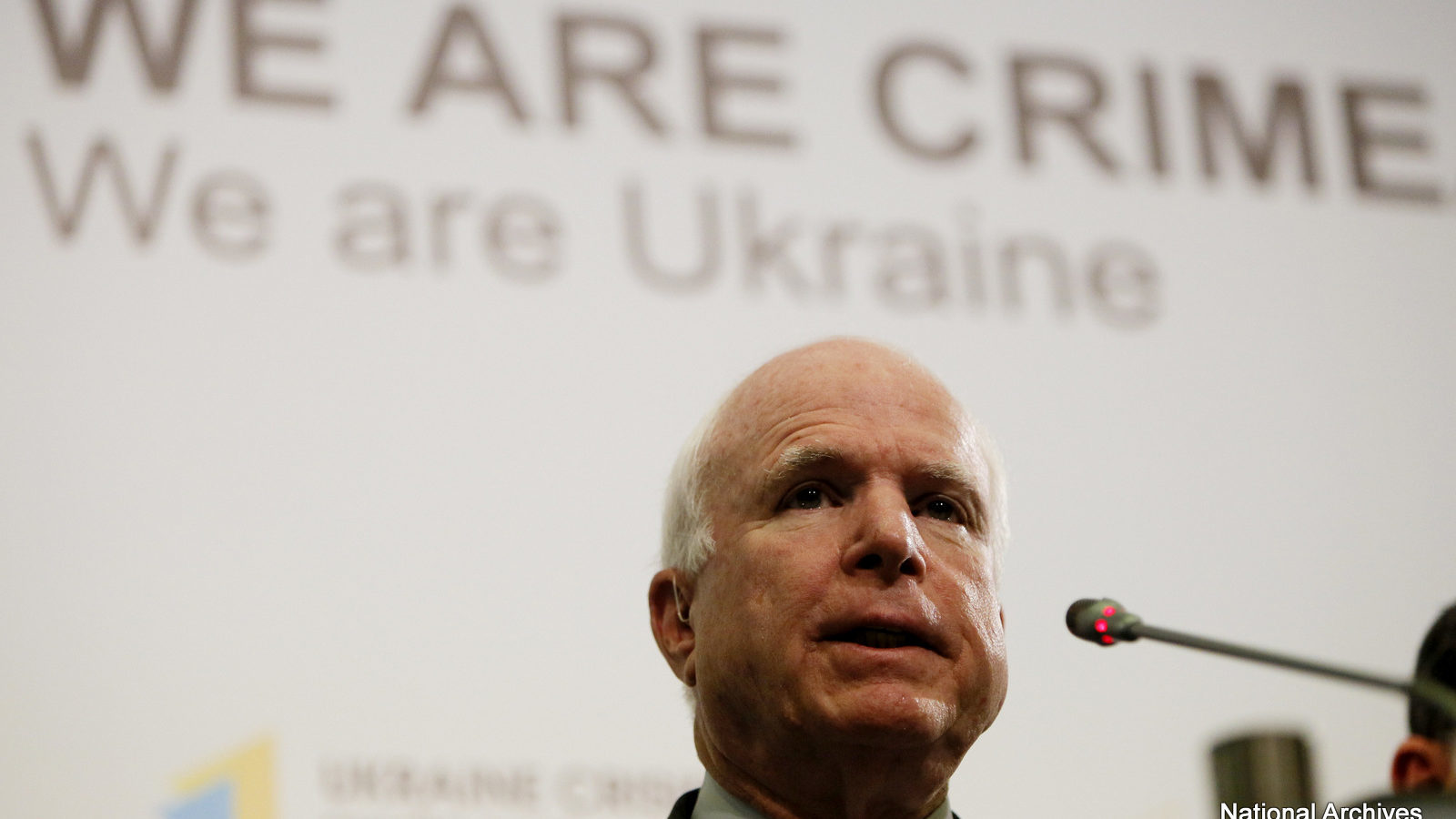

The enemy is dead... May the Lord accept his dark soul and determine its future."Over the course of countless congressional recesses, Senator McCain's travelogue included trips across Southeastern Europe, the Caucasus, and former Soviet states such as Georgia and Ukraine. This led many in Russia to believe that McCain had an obsessive loathing for Russia as a nation, regardless of the bygone anti-communism of the Cold War cauldron within which his career had been forged.

General Vladimir Dzhabarov, a senator and deputy chairman of the Federation Council's Foreign Affairs Committee, noted that post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from McCain's Vietnam War shootdown and imprisonment may have played a role in the politician's hatred of Russia:

Mr. McCain was always an American patriot. Unfortunately, however, the 'Vietnam Syndrome' had affected him all his life... He was an outspoken Russophobe over the past decades. Not only did he simply dislike our country, but he in fact hated it. Peace be upon him."Portrait of an anti-Russian crusader

It can be said either that Senator McCain was a Cold War fossil who couldn't break from the habit of referring to the Russian Federation as the "Soviet government," or that he was a visionary U.S. politician who understood the irreconcilable interests at stake in Washington's relations with Moscow - and the fact that the two governments were destined to remain bitter rivals.

McCain began advocating confrontation with Russia during the 1990s, when he saw Russia as backing Serbia versus NATO in a kabuki dance of sorts that merely masked a trend moving toward high-stakes conflict. It was at this time that the "maverick" began to excoriate the Clinton administration for its naive view that democracy could be achieved in Russia.

In 2003, the arrest of oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky convinced the Republican neoconservative McCain and his longtime Democratic counterpart Joe Lieberman that all hope was lost for the cause of "freedom" in Russia. The two began to set in motion their push to expel Russia from the Group of Eight (G8) industrialized nations. Following its annexation of Crimea in March 2014, Russia was finally suspended from the group.

At the Munich Security Conference in February, 2007, Russian President Vladimir Putin bluntly unveiled Russia's newfound assertiveness while rattling off a litany of Moscow's grievances with Washington, marking a solid break from the largely inconsequential partnership the two capitals nominally enjoyed following the World Trade Center attacks of September 11, 2001.

Putin's comments were shorn of any "diplomatic niceties," as the Russian leader had warned in advance, and were marked by a tense moment when Putin stared down Senators McCain and Lieberman, as well as then-U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates. While Gates laughed off Putin's theatrics, the legislators were visibly unsettled - with McCain even looking away, laughing in embarrassment. How dare the Russian leader act with such impudence!

McCain grew obsessive in his resentful attitude toward Moscow, and his hawkishness only grew as Putin followed through on his pledge to not behave as a U.S. vassal - an announcement the Russian leader made good on in 2008, when Russian Armed Forces columns crossed into South Ossetia to mete out a humiliating defeat to close McCain comrade and Georgian leader Mikhail Saakashvili.

At the time, McCain told reporters:

I think it's very clear that Russian ambitions are to restore the old Russian Empire ... Not the Soviet Union, but the Russian Empire."The trend merely repeated itself in Ukraine and Syria, with McCain's cries for anti-Russian measures growing shriller with each perceived "attack" by Putin on the so-called democratic world. McCain's red lines were innumerable, and the hawkish lawmaker seemed willing to plunge the globe into a third world war if it meant teaching Putin a lesson.

A career sailor, grandson and son of four-star U.S. Navy admirals, McCain died with his personal enemy Donald J. Trump seated as commander-in-chief of the U.S. Armed Forces. McCain was hardly shy about his distrust and anger over Trump's attempts to seek rapprochement with Russia.

In May, McCain referred to Putin as an "evil man" plotting "evil deeds," dramatically commenting:

Putin's goal isn't to defeat a candidate or a party. He means to defeat the West ... He meddled in one election, and he will do it again because it worked and because he has not been made to stop."As a "prophet" of an anti-Russian hysteria whose popularity among U.S. imperialist elites had shrunk following the collapse of the Soviet Union, McCain suffered the final stages of brain cancer basking in the glory of his success in not only keeping Russophobia alive, but in helping it metastasize once again across U.S. political culture.

Elliott Gabriel is a former staff writer for teleSUR English and a MintPress News contributor based in Quito, Ecuador. He has taken extensive part in advocacy and organizing in the pro-labor, migrant justice and police accountability movements of Southern California and the state's Central Coast

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter