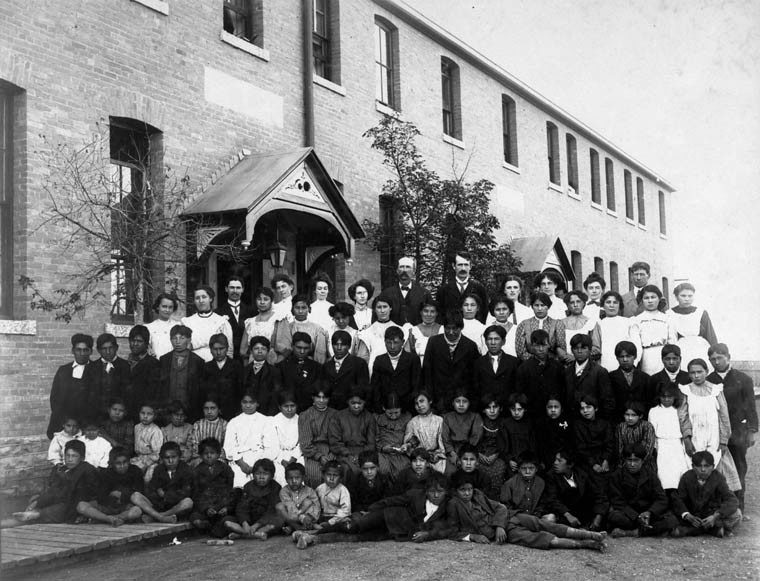

It's true that while we're very quick in this country to apologize for, say, cutting somebody off in line at Tim Horton's, we're less than prompt at apologizing for the really big stuff - like the century-long policy know as the Canadian Indian residential school system, which forcibly removed indigenous children from their families. The first real apology on behalf of the Canadian government didn't come until 2008, when then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper acknowledged the excesses of the residential school system, and that the system itself had been a crime. This was a first - and it took 130 years since the creation of the Indian Act in 1876, which led to the system's creation.

In a way, Harper's apology was premature. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada would not issue its final report on the crimes committed by the Canadian government - and their literal partners-in-crime, the Catholic and Protestant churches - until 2015. After a decade of digging into the annals of the residential school system, it produced a raft of statistics that astonished most Canadians (at least those who deigned to pay attention). Here is but a taste of what the report revealed:

- Over 150,000 indigenous children across Canada (nearly one out of three indigenous children) were forcibly removed from their parents and placed in church-run residential schools between 1876 and the closure of the final school in 1996 (yes, 1996, the same year the Spice Girls released "Wannabe").

- More than 6,000 children are confirmed to have died while attending residential schools, with some estimates placing the death toll at three times this number. But even the most conservative estimates still give children in the Indian residential school system a higher mortality rate than Canada's fighting forces during World War II.

- During the early years of the system, as many as half of the children may have died of tuberculosis. This was as a result of shockingly poor sanitation and lack of access to healthcare. According to a 1907 report, as many as 69 percent of students at one unnamed school may have died.

- Official death tolls from the residential schools are still a matter of debate as a result of poor record-keeping on the part of the schools - and the fact that dead children were typically interred in unmarked graves.

- Some 32,000 children in the residential school system were physically and/or sexually abused, with a further 5,995 claims of such abuse still under investigation as of the tabling of the final report. Again, for the sake of perspective, that's nearly a quarter of all attendees.

- Residential schools were typically underfunded and relied largely on forced child labour to remain solvent.

- Between 1942 and 1952, nutrition research and human biomedical experiments were carried out on Aboriginal children in residential schools, with the endorsement of federal and provincial governments. In some cases children were deliberately malnourished for experimental purposes.

- Parental visitation was all but prevented by the "pass system" imposed in 1885 and enforced by government Indian Agents, which kept indigenous people confined to reserve land. Schools were also deliberately situated in remote locations (of which there's no shortage in Canada) so as to discourage parental visits.

- Children were routinely physically beaten or forced to eat soap for the "crime" of speaking their native languages.

- A sample of 127 residential school survivors revealed that some 65 per cent had incurred post-traumatic stress disorder.

By the late 1950s, criticism of the residential school system (or at least its excesses) had become widespread, and the system was on the wane. But that didn't mean that mainstream (i.e. white) Canadian society was ready to let indigenous people parent their own children.

From the 1950s until the 1980s, an estimated 20,000 aboriginal children were once again wrenched from their families and placed in foster care or with adoptive white middle-class families as part of the so-called Sixties Scoop (sometimes also the Seventies Scoop). As of 1977, approximately 15,500 indigenous children were in foster care, representing roughly 20 per cent of all children in the child welfare system - in spite of being only five per cent of the total population.

The western provinces were especially aggressive in prosecuting the scoop, with aboriginal children representing 40-50 percent of foster children in Alberta, 60-70 percent in Saskatchewan, and 50-60 percent in Manitoba. In many cases children were removed from their parents by child and family services personnel without the parents even being informed.

The consequences of over a century of government-sanctioned destruction of indigenous families and communities are starkly depicted by modern statistics. According to a 2016 study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, some 51 percent of First Nations children live in poverty, a rate that increases to 60 percent for children who live on First Nations reserves. Again, the rates are highest in the western prairie provinces, with a staggering 76 percent poverty rate for Aboriginal children in Manitoba and a 69 percent rate in neighboring Saskatchewan. Mental health problems abound in First Nations reserves, and intergenerational cycles of sexual abuse remain a massive unresolved problem. Indigenous youth commit suicide at roughly six times the rate of non-indigenous youth.

Meanwhile, as of 2011 some 3.6 percent of all indigenous children aged 14 and under remain in foster care, compared to 0.3 percent of non-indigenous children.

In spite of this horrifying history, a disturbing number of Canadians - including people who really ought to know better - continue to defend the indefensible. Former Conservative senator for Ontario Lynn Beyak notoriously threw shade at the TRC in 2017, alleging that its final report overlooked the "good deeds" accomplished by "well-intentioned" religious teachers. As with the system's earliest proponents, Senator Beyak's defense was rooted in religious conviction, adding that it was unfair to brand Hector-Louis Langevin, a Father of Confederation and one of the system's chief architects, as a racist given that students "learned valuable teachings about Jesus and the Gospel." (Beyak has since been booted from the Senate and the federal Conservative Party, but remains an independent candidate in her Ontario riding.)

Lessons for Trumpian America

The United States of America of course also has a lengthy legacy of forcibly separating parents from their children, ranging from the formal practice of slavery (in which it was a standard feature) to practices similar to those employed in Canada regarding Native American children.

In fact, one is hard-pressed to find a colonial society anywhere that hasn't practiced some form of this. Australia has its "Stolen Generation" legacy. The Group Areas Act in Apartheid-era South Africa had the result in many cases of forcing families apart, particularly mixed-race families (a fact that comedian Trevor Noah brought to public attention in his autobiography Born A Crime). In Korea, during World War II, some 450,000 male laborers were forcibly relocated to Japan, while between 10,000 to 200,000 women were forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military.

Separating children from their families has long been a part of colonial subjugation. It also - suffice it to say - never ends well. What do any of Trump's immigration policy defenders think is going to happen to these children, who presumably will be at the mercy of a child and welfare system supported by the American taxpayer?

In large part, the current influx of asylum seekers from Central America is a consequence of US immigration policy. It was an outflow of former illegal migrants to the US from El Salvador and elsewhere in the 1980s that fed into the ranks of MS-13 and other violent gangs, which in turn transformed cities like San Salvador, San Pedro Sula, and Guatemala City into bullet-ridden war zones from which current migrants are attempting to escape.

It's worth re-examining America's history as a de facto colonial power in countries where current migrants are coming from. From the issuance of the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 (which coincided with much of Latin America's newfound independence from Spain) to today, US involvement in Central America and the Caribbean has ranged from relatively benign economic and military support to brazenly heavy-handed intervention based on completely self-serving geopolitical and economic goals. These "interventions" ranged from overthrowing democratically elected Guatemalan president Jacobo Árbenz in 1954 (at the behest of United Fruit Company), training and arming the death squads that terrorized the El Salvadoran and Nicaraguan countrysides during those countries' respective civil wars, to propping up thuggish puppet leaders like Jorge Ubico in Guatemala, Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua, and Fulgencio Batista in Cuba.

Americans who might take umbrage at my comparison of Trump's immigration policy with Canada's residential school system - on the grounds that Canada "did it to its own people" - might want to revisit their country's history. It's also worth remembering that, for most of the time Canada's residential schools were in operation, Canada's First Nations were denied the right to vote (they gained it in 1960). In other words, at the time native children were being rounded up and forced into residential schools, their parents had about as much say in matters of government policy than the Guatemalan or Nicaraguan peasantry in the 1950s or 1980s had over US foreign policy in their countries. Same colonialism, different pile.

Thankfully, in Canada at least - knuckle-draggers like Lynn Beyak notwithstanding - admirable steps have been taken in recent years to address the country's horrifying legacy of cultural genocide and of the systematic destruction of indigenous family and community networks. Much more remains to be done, and far too many Canadians are still woefully ignorant of the country's appalling history of racist abuse against aboriginal children and families, but it has nonetheless been reassuring to see the considerable consternation on social media and elsewhere over Trump's monstrous attack on asylum-seeking families on the part of Canadians (and others) who see echoes of their own history. It's deeply disturbing - because it's all deeply familiar.

Hearing Fox News' Laura Ingraham liken the child detention facilities that have been set up at the US-Mexico border to a "summer camp," to which the Twitterverse quickly (and rightly) responded with disgust, struck me as simply another case of a Fox News pundit saying something asinine - in other words, completely par for the course. Fewer people, however, noticed that she also described the facilities as "like a boarding school". But given our own history here in Canada, it's the latter remark that scares me the most. Doing exactly this to children and families was our official government policy here for a very long time, and we're still very much contending with the consequences.

If there's ever been a government policy anywhere on earth predicated on prying families apart that wasn't an epic disaster, I have yet to hear about it. And saying soary, eh after the fact never cuts it.

Comment: See also: Trudeau criticizes Trump over illegal immigration, while Canada keeps illegal immigrant children in prison and under surveillance