Researchers say they were largely driven by changes in sea level and associated environmental change.

However, they say it is still an 'open question' whether it will recover from the current crisis, caused by coral bleaching.

Over millennia, the reef has adapted to sudden changes in environment by migrating across the sea floor as the oceans rose and fell - but say this might not be enough to deal with the current crisis.

The 10-year, multinational effort has shown the reef is more resilient to major environmental changes such as sea-level rise and sea-temperature change than previously thought - but also showed a high sensitivity to increased sediment input and poor water quality.

Comment: Worldwide ocean anoxia driven by global cooling was possible factor in previous mass extinctions

'Our study shows the reef has been able to bounce back from past death events during the last glaciation and deglaciation,' said the University of Sydney's Associate Professor Jody Webster.

Webster said it remains an open question as to whether its resilience will be enough for it to survive the current worldwide decline of coral reefs.

The study used data from geomorphic, sedimentological, biological and dating information from fossil reef cores at 16 sites at Cairns and Mackay.

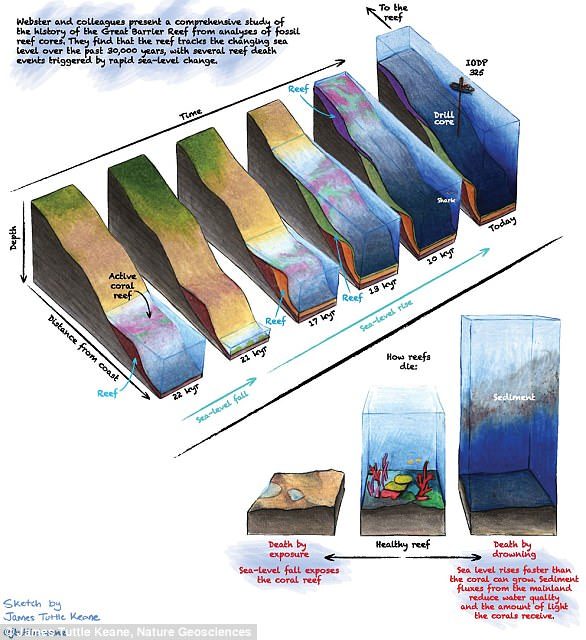

The study covers the period from before the 'Last Glacial Maximum' about 20,000 years ago when sea levels were 118 metres below current levels.

As sea levels dropped in the millennia before that time, there were two widespread death events (at about 30,000 years and 22,000 years ago) caused by exposure of the reef to air, known as subaerial exposure.

During this period, the reef moved seaward to try to keep pace with the falling sea levels.

During the deglaciation period after the Last Glacial Maximum, there were a further two reef-death events at about 17,000 and 13,000 years ago caused by rapid sea level rise.

These were accompanied by the reef moving landward, trying to keep pace with rising seas.

Analysis of the core samples and data on sediment flux show these reef-death events from sea-level rise were likely associated with high increases in sediment.

The final reef-death event about 10,000 years ago, from before the emergence of the modern reef about 9000 years ago, was not associated with any known abrupt sea-level rise or 'meltwater pulse' during the deglaciation.

The authors propose that the reef has been able to re-establish itself over time due to continuity of reef habitats with corals and coralline-algae and the reef's ability to migrate laterally at between 0.2 and 1.5 metres a year.

However, Associate Professor Webster said it was unlikely that this rate would be enough to survive current rates of sea surface temperature rises, sharp declines in coral coverage, year-on-year coral bleaching or decreases in water quality and increased sediment flux since European settlement.

WHAT IS CORAL BLEACHING?

Corals have a symbiotic relationship with a tiny marine algae called 'zooxanthellae' that live inside and nourish them.

When sea surface temperatures rise, corals expel the colourful algae. The loss of the algae causes them to bleach and turn white.

This bleached states can last for up to six weeks, and while corals can recover if the temperature drops and the algae return, severely bleached corals die, and become covered by algae.

In either case, this makes it hard to distinguish between healthy corals and dead corals from satellite images.

This bleaching recently killed up to 80 per cent of corals in some areas of the Great Barrier Reef.

Bleaching events of this nature are happening worldwide four times more frequently than they used to.

Associate Professor Webster said previous studies have established a past sea surface temperature rise of a couple of degrees over a timescale of 10,000 years. However, current forecasts of sea surface temperature change are around 0.7 degrees in a century.

'Our study shows that as well as responding to sea-level changes, the reef has been particularly sensitive to sediment fluxes in the past and that means, in the current period, we need to understand how practices from primary industry are affecting sediment input and water quality on the reef,' he said.

Comment: Ocean currents have been shown to be the weakest in over 1,600 years, with an overall drop in temperatures and low oxygen levels, as well as in many areas sea level appears to be dropping (or the land is rising, or both), while at the same time due to increasing storm activity the oceans are becoming more destructive. But as noted in the article, all hope is not lost, our planet seems to always recover: