OF THE

TIMES

A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual doom.

Hitler (and his party) did not seize power. The Nazis did well in the elections and were able to form a coalition government. After the Reichstag...

There is nowhere to run and hide from the NWO and its nato poodle. Meanwhile the US senate tells zelensky to curb his stealing. Must be a jew...

"Maybe the real trauma was realizing that the majority of injuries and fatalities were due to the actions of the IDF, the 'invincible' force that...

Come back home to be treated like dirt first for trying to avoid being killed uselessly, then be killed. Going ''underground'' (pun not intended)...

In this age of female equality (and Ukraine loves Western values we are told) why is this legal passport restriction only applied to men? Will all...

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

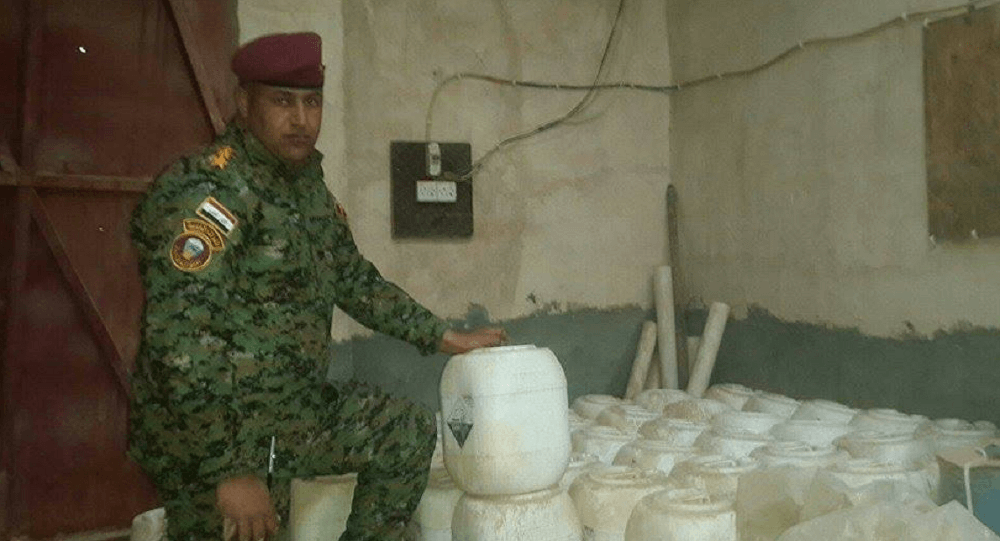

Comment: Western media dare not call attention to the fact that terrorists regularly use chemical weapons when the puppet masters are in the midst of a propaganda frenzy to lay all blame for the recent 'gas attack' in Syria on Assad's government. Can't have the sheeple asking questions or doubting the narrative.