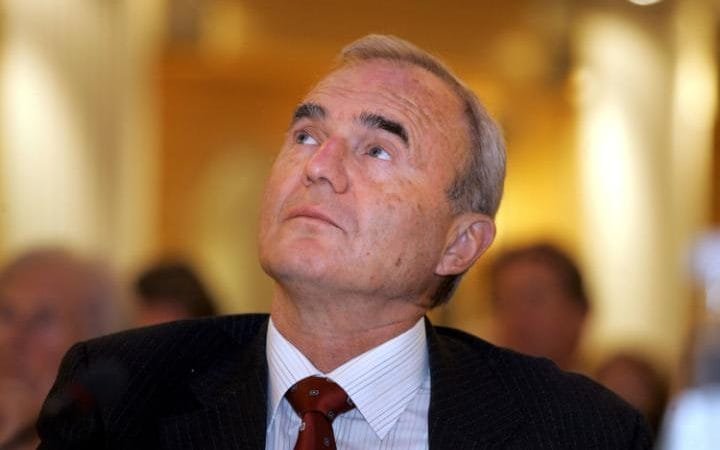

© AFP/GETTY IMAGESOtmar Issing was a towering figure at the euro's inception

The European Central Bank is becoming dangerously over-extended and the whole euro project is unworkable in its current form, the founding architect of the monetary union has warned.

"One day, the house of cards will collapse," said Professor Otmar Issing, the ECB's first chief economist and a towering figure in the construction of the single currency.

Prof Issing said the euro has been betrayed by politics, lamenting that the experiment went wrong from the beginning and has since degenerated into a fiscal free-for-all that once again masks the festering pathologies."Realistically, it will be a case of muddling through, struggling from one crisis to the next. It is difficult to forecast how long this will continue for, but it cannot go on endlessly," he told the journal

Central Banking in a remarkable deconstruction of the project.

The comments are a reminder that the eurozone has not overcome its structural incoherence. A beguiling combination of cheap oil, a cheap euro, quantitative easing and less fiscal austerity have disguised this, but the short-term effects are already fading.

The regime is almost certain to be tested again in the next global downturn, this time starting with higher levels of debt and unemployment, and greater political fatigue.

Prof Issing lambasted the European Commission as a creature of political forces that has given up trying to enforce the rules in any meaningful way. "The moral hazard is overwhelming," he said. The ECB is now buying corporate bonds that are close to junk, and the haircuts can barely deal with a one-notch credit downgrade

The European Central Bank is on a "slippery slope" and has in his view fatally compromised the system by bailing out bankrupt states in palpable violation of the treaties."The Stability and Growth Pact has more or less failed. Market discipline is done away with by ECB interventions. So there is no fiscal control mechanism from markets or politics. This has all the elements to bring disaster for monetary union.

"The no bailout clause is violated every day," he said, dismissing the European Court's approval for bailout measures as simple-minded and ideological.

The ECB has "crossed the Rubicon" and is now in an untenable position, trying to reconcile conflicting roles as banking regulator, Troika enforcer in rescue missions and agent of monetary policy. Its own financial integrity is increasingly in jeopardy.The central bank already holds over €1 trillion of bonds bought at "artificially low" or negative yields, implying huge paper losses once interest rates rise again. "An exit from the QE policy is more and more difficult, as the consequences potentially could be disastrous," he said.

"The decline in the quality of eligible collateral is a grave problem. The ECB is now buying corporate bonds that are close to junk, and the haircuts can barely deal with a one-notch credit downgrade. The reputational risk of such actions by a central bank would have been unthinkable in the past," he said.

Cloaking it all is obfuscation, political mendacity and endemic denial. Leaders of the heavily indebted states have misled their voters with soothing bromides, falsely suggesting that some form of fiscal union or debt mutualisation is just around the corner.Yet there is no chance of political union or the creation of an EU treasury in the forseeable future, which would in any case require a sweeping change to the German constitution - an impossible proposition in the current political climate. The European project must therefore function as a union of sovereign states, or fail.The Greeks should have been offered generous support, but only after it had restored exchange rate viability by returning to the drachma

Prof Issing slammed the first Greek rescue in 2010 as little more than a bailout for German and French banks, insisting that it would have been far better to eject Greece from the euro as a salutary lesson for all. The Greeks should have been offered generous support, but only after it had restored exchange rate viability by returning to the drachma.

His critique will exasperate those at the ECB and the International Monetary Fund who inherited the crisis, and had to deal with a fast-moving and terrifying situation.

The fear was a chain-reaction reaching Spain and Italy, detonating an uncontrollable financial collapse. This nearly happened on two occasions, and remained a risk until Berlin switched tack and agreed to let the ECB shore up the Spanish and Italian debt markets in 2012.

Many would say the crisis mushroomed precisely because the ECB was unable to act as a lender-of-last resort. Prof Issing and others from the Bundesbank were chiefly responsible for this design flaw.

Jacques Delors, the euro's "political" founding father, issued his own candid

post-mortem last month on the failings of EMU but disagrees starkly with Prof Issing about the nature of the problem.

His foundation calls for a supranational economic government with debt pooling and an EU treasury, as well as expansionary policies to break out of the "vicious circle" and prevent a second Lost Decade.

"It is essential and urgent: at some point in the future, Europe will be hit by a new economic crisis. We do not know whether this will be in six weeks, six months or six years. But in its current set-up the euro is unlikely to survive that coming crisis," said the Delors report.Prof Issing is not a German nationalist. He is open to the idea of a genuine United States of Europe built on proper foundations, but has warned repeatedly against trying to force the pace of integration, or to achieve federalism "

by the back door".

Such a system would erode the budgetary sovereignty of the member states and violate the principle of no taxation without representation

He decries the latest EU plan for a "fiscal entity" in the

Five Presidents' Report, fearing that such move would lead to a rogue plenipotentiary with unbridled powers over sensitive issues of national life, beyond democratic accountability.

Such a system would erode the budgetary sovereignty of the member states and violate the principle of no taxation without representation, forgetting the lessons of the English Civil War and the American Revolution.

Prof Issing said the venture began to go off the rails immediately, though the structural damage was disguised by the financial boom. "There was no speed-up of convergence after 1999 - rather, the opposite. From day one, quite a number of countries started working in the wrong direction."

A string of states let rip with wage rises, brushing aside warnings that this would prove fatal in an irrevocable currency union. "During the first eight years, unit labour costs in Portugal rose by 30pc versus Germany. In the past, the escudo would have devalued by 30pc, and things more or less would be back to where they were."

"Quite a few countries - including Ireland, Italy and Greece - behaved as though they could still devalue their currencies," he said.

The elemental problem is that once a high-debt state has lost 30pc in competitiveness within a fixed exchange system, it is almost impossible to claw back the ground in the sort of deflationary world we face today.

It has become a trap. The whole eurozone structure has acquired a contractionary bias. The deflation is now self-fulling. Prof Issing's purist German ideology has no compelling answer to this.

Professor BS knows as much about economics as the guys picking the garbage in my neighborhood. They are more useful than he is. The euro is not going to collapse unless the Rothschild so wish, which is something they do not wish and not only that, they can back up their wish. The Telegraph : Another U.K. rag. @Sott : Check your sources

people.