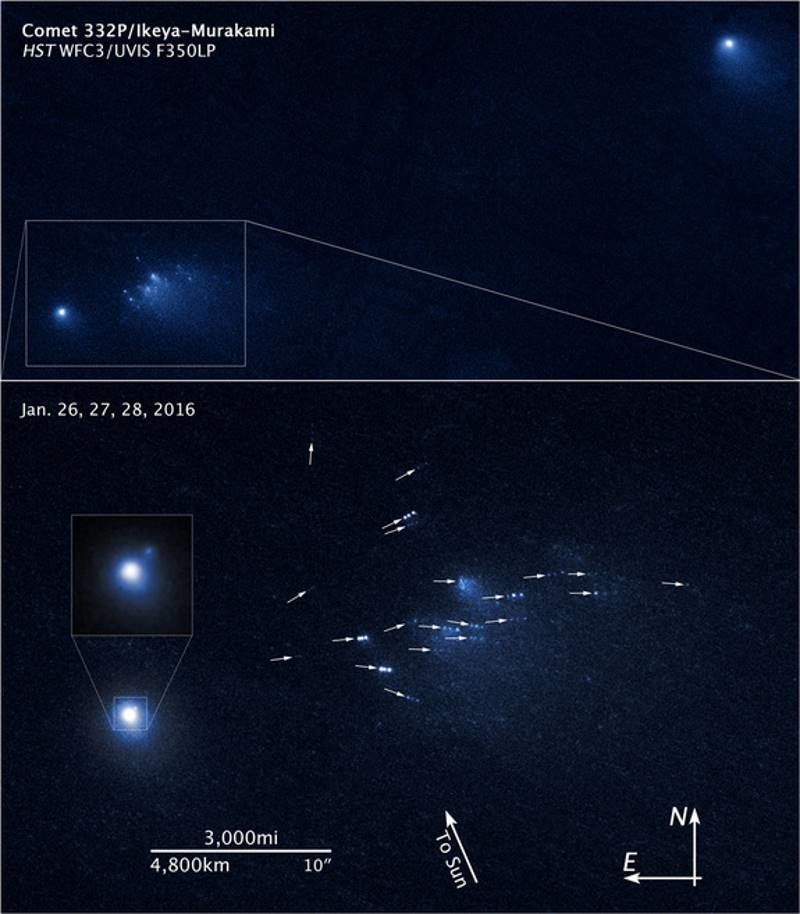

Over the span of three days in January 2016, the Hubble Space Telescope captured detailed images of just that scenario happening to Comet 332P/Ikeya-Murakami, or Comet 332P, located roughly 67 million miles from Earth.

The Hubble observations revealed 25 building-size blocks made of a mixture of ice and dust that broke off from the comet and are now are scattered along a 3,000-mile-long trail, larger than the width of the continental U.S. The icy chunks comprise about 4 percent of the parent comet and range in size from roughly 65 feet wide to 200 feet wide. They are drifting away from the comet and each other at a few miles per hour, about the walking speed of an adult. See animation here.

The Hubble observations also reveal that the comet is much smaller than previously thought, measuring only 1,600 feet across, about the length of five football fields.

According to a NASA statement, these observations provide insight into the volatile behavior of comets as they approach the sun, begin to vaporize, and unleash dynamical forces. Comet 332P was 150 million miles from the sun, slightly beyond the orbit of Mars, when Hubble spotted the breakup.

"We know that comets sometimes disintegrate, but we don't know much about why or how they come apart," explained UCLA's David Jewitt. "The trouble is that it happens quickly and without warning, and so we don't have much chance to get useful data. With Hubble's fantastic resolution, not only do we see really tiny, faint bits of the comet, but we can watch them change from day to day. And that has allowed us to make the best measurements ever obtained on such an object."

Comet 332P was discovered in November 2010 by two Japanese amateur astronomers, Kaoru Ikeya and Shigeki Murakami.

Based on the Hubble data, the research team estimates the comet probably shed material over several months, between October and December 2015. Jewitt suggests that even some of the ejected pieces have themselves fallen to bits in a kind of cascading fragmentation.

Hubble also imaged a chunk of material close to the comet, which may signal another outburst. A fragment from yet an older flare-up, which may be as large as Comet 332P, is also visible, suggesting the comet split in two.

That icy remnant was spotted in Dec. 31, 2015, by the Pan-STARRS telescope in Hawaii. It was that initial discovery which prompted Jewitt and colleagues to request Hubble time to look at the comet in detail. Around the same time, astronomers around the world began to notice a cloudy patch of material near the comet - which Hubble later resolved into the 25 pieces.

"In the past, astronomers thought that comets die when they are warmed by sunlight, causing their ices to simply vaporize away," Jewitt said. "Either nothing would be left over or there would be a dead hulk of material where an active comet used to be. But it's starting to look like fragmentation may be more important. In Comet 332P we may be seeing a comet fragmenting itself into oblivion."

"Hubble's best previous glimpse at a fragmenting comet came during Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) observations of 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 (73P) in April 2006," said Harold Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. "In those observations, Hubble witnessed a comet with more than 60 named pieces. The Hubble images showed unprecedented detail of 73P's breakup, but the comet wasn't observed long enough to document the evolution of the fragments over time, unlike the case of 332P."

The researchers estimate that Comet 332P may have enough mass for at least 25 more outbursts.

"If the comet has an episode every six years, the equivalent of one orbit around the sun, then it will be gone in 150 years," Jewitt said. "It's the blink of an eye, astronomically speaking. The trip to the inner solar system has doomed it."

A study based on these findings is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"Editor by trade, artist by design." Lola Gayle is a Texas-based science writer and editor with over 16 years of experience in the business. When she's not researching and writing for STEAM Register, she spends her time supporting wildlife conservation efforts, pet adoptions, and STEM/STEAM education.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter