... Well, it doesn't have quite the ring of the better known poem that, having once landed Erdogan in jail, has now ensured his survival.

So people are now asking: Without Erdogan's closer ties to a religion far more passionary than Orthodox Christianity, without his allegedly superior democratic credentials, would anyone actually bother out to defend the Dark Lord of the Kremlin cometh the Great Day of his Reckoning that every second Russia think-tank analyst in London and Washington D.C. has been prophesying for more than a decade?

Of course not. I even feel a bit stupid for putting fingers to keyboard to write this post. But nonsense has to be cleared up.

I

The first problem with thinking about a prospective Russian coup is finding even a semi-plausible candidate to play the plotters' part.

The actors that immediately come to mind are the generals - but they are also the unlikeliest group to move against Putin. The last time the Russian armed forces had regularly played kingmaker was during the 17th century, when the streltsy acted as a kind of Praetorian guard to the Tsars. The last successful coup that relied on military support took place more than two century ago, when Catherine the Great deposed the wildly unpopular Peter III, an 18th century Wehraboo who had withdrawn Russia from a hard-fought but successful war against Prussia on account of his boyhood fascination with Frederick the Great and the Prussian Army. The Russian military would never again be politically influential. The Kornilov putsch in 1917 failed. In both 1991 and 1993, the Armed Forces remained loyal to their respective heads of state, Gorbachev and Yeltsin, even though neither man enjoyed their respect. Despite the frailty of post-Soviet polities, the entire region would only see three military coups after 1991: One successful coup in Georgia, and two coups in Azerbaijan, of which one was successful. Azerbaijan is, of course, the closest "relative" to Turkey - with its seven coups this past century alone - in the former USSR, so it is unlikely that its experience would be much extensible to Russia.

In contrast to both Gorbachev and Yeltsin, Putin has enjoyed consistently high approval ratings, and the respect of the military and siloviks [Russian politicians from the old security or military services, often KGB, FSB, and military officers or other security services - ed.] in particular. He can speak their language and has furnished lavish spending on both the military and the security services. The current Defense Minister, Sergey Shoigu, is highly popular without harboring much in the way of personal political ambitions of his own. This is in contrast to his predecessor Anatoly Serdyukov, who was highly unpopular for his questionable reforms and blatant corruption. He was eventually dismissed from his post, but the corruption investigation went nowhere and was eventually quietly shut down. Although the legal impunity of the Russian political elites is one of the few real sources of popular discontent with Putinism, it may also play a role as a political safety valve. Bureaucrats who steal too much - Serdyukov, Yakunin, Luzhkov, etc. - might get dismissed, but don't tend to go overtly hostile because, apart from their low chances of success and high risk of ruin, they also know that the next regime might not be so forgiving towards them.

It is ultimately the oligarchs who are the most credible threat to Putin's power. After all, it was the oligarchs who were instrumental in keeping an ailing Yeltsin in power in 1996, who ruled it for a time as the Semibankirschina, ["Seven Bankers" - ed.] and who eased the transition towards a Putin Presidency (upon which he promptly told them to get out of politics). They also played a huge role in the political life of the other post-Soviet states. In Georgia, it was essentially an oligarchic coup by the billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili that doomed Saakashvili's attempts to set himself up for permanent rule in late 2012. In Ukraine, it was above all the defection of several key oligarchs critical to the coalition supporting Viktor Yanukovych - together with their media assets and bought up Rada MPs - that ensured the success of Euromaidan (though a false flag helped). Moldova is essentially a playground for various oligarchic and nationalist factions. So oligarchs have a record of successfully influencing politics throughout the former USSR, and moreover, as a class they have no particular reasons to love Putin. So how much of a threat are they?

They are a bigger threat than any other force, but still not all that dangerous. First, there has already been stringent selection for loyalty; recalcitrants (Gusinsky, Berezovsky, Khodorkovsky, etc.) have long been purged or exiled abroad. The 1990s class of oligarchs, who have the most reason to hate Putin, now have very little institutional influence. Khodorkovsky tried to infiltrate the system by buying up Duma MPs in the early 2000s, which no doubt contributed to the decision to bring down the hammer of the law against him. Since his release he has said he wants to lead Russia (thus once again breaking his promise not to go into politics), but his main political asset is but a slick PR campaign centered almost exclusively on the West. How that could translate into meaningful political power in Russia is unclear to say the least.

Meanwhile, the large class of billionaires created in the 2000s has no particular reason to dislike Putin, especially since he was the man who enabled many of them to acquire or expand their fortunes; nor do they have much in the way of political influence, since staying out of politics was a condition of them being allowed to do large-scale business in the first place (Mikhail Prokhorov's 2008 Presidential run was a mutually agreed upon exception). The supportive political role of the AKP-linked construction barons in Erdogan's Turkey, who have gotten rich on providing homes and malls for Anatolians moving to the western cities, is in Russia played by a small group of Putin's friends, who get privileged contracts in return for their loyalty and helping out with projects of national importance. Is this corrupt? Sure. But on the flip side, nobody apart from the Roternbergs was rushing to build a bridge to Crimea, because they have too many assets tied up in the West. Incidentally, speaking of the West, far from destabilizing Putin's domestic position as initially hoped for, the sanctions on Russian figures close to Putin have only strengthened Putin's position, since they are more reliant on his favor than ever before now that the option of fleeing to Londongrad has been foreclosed.

II

But okay, let's put all that aside and wave a magic wand.

While Putin is away at a UN summit, his approval at a record low due to a recent crab-related sex scandal, a group of oligarchs manage to buy off the directors of most of the main TV channels, a large chunk of United Russia MPs, and the head of the Moscow police and OMON. Putin's Cabinet are taken into custody. Khodorkovsky and the rest of his merry revolutionaries jet in, while Putin's plane is discovered to have mechanical problems (a group of men are seen furtively sneaking out of the hangar), delaying his return to Russia for a number of critical hours.

In this scenario, will the coup go ahead successfully, the now liberal-controlled state TV brainwashing vatnik brains overnight into avid becoming avid supporters of Khodorkovsky and holding a gay parade in his honor, or will they take to the streets to preserve their democratically elected President/evil totalitarian regime (cross out as appropriate)?

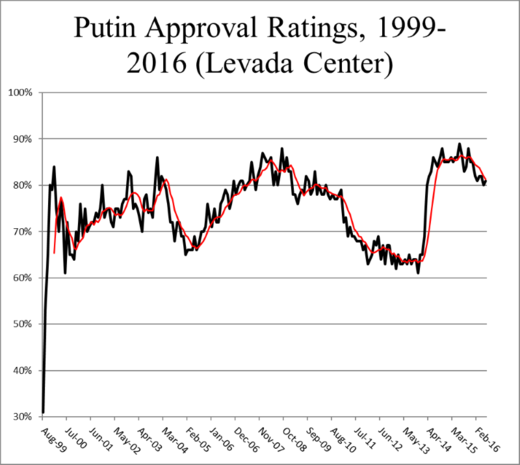

Well, the first and most obvious "problem" is that Putin's approval rating has hovered at a steady 60%-90% through the 16 years of his rule.

Color revolutions, even coups, are pretty much impossible with these kinds of ratings. Yanukovych was in his 20%'s on the eve of Euromaidan (similar to Poroshenko today), and even lower in Kiev. Even the failed recent coup against Erdogan occured when he was in his 40%'s. All three of the post-Soviet coups came at a time of double-digit annual GDP collapse and civil war/failed war against Armenia. Despite political crises in 1961 and 1968, there was never a successful coup against France's Charles de Gaulle, the postwar West European leader with whom Putin perhaps has the most commonalities; between 1958 and 1969, De Gaulle's approval ratings averaged 60% (Putin: 75%), and never dipped below 42% (Putin: Low 60%'s).

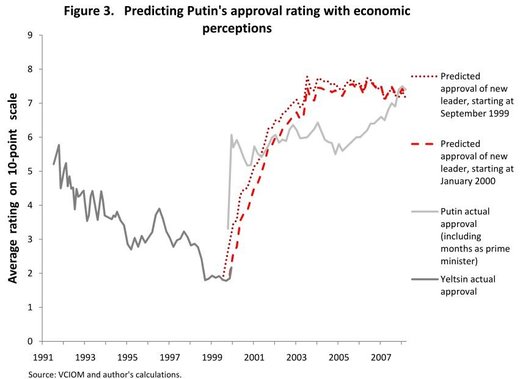

One popular theory advanced by Daniel Treisman used to explain Putin's Teflon-like popularity (and popularized in his book The Return) tied Putin's (and Yeltsin's) approval ratings to economic performance.

However, as it later emerged, this tight correlation must have been an artifact. It broke down to the downside during the 2011-12 protests over electoral falsifications, even though the economy then was chugging along more or less normally; and it veered sharply upwards after the incorporation of Crimea in 2014, even as the economy went into a long recession.

So you can't rely on sanctions and/or The Next Recession to torpedo Putin's ratings.

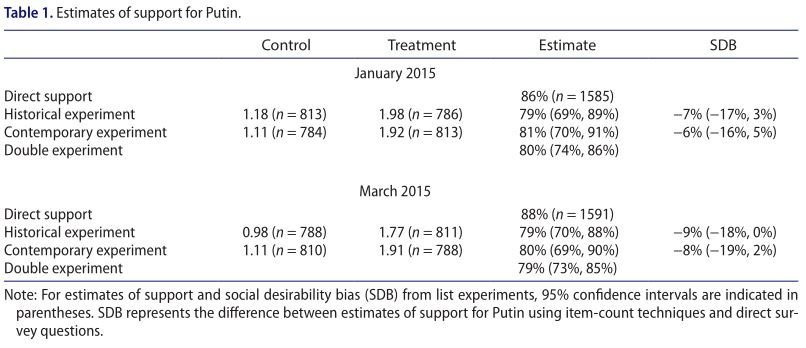

Another popular theory is that Russian pollsters are unreliable. It is also incredibly illogical, since the Levada Center is for all intents and purposes an oppositional organization, and because even Western pollsters consistently confirm Putin's high approval ratings.

The most nuanced critique is the "mile wide but inch deep" theory of post-Soviet politics, which as repeatedly applied to Putin's Russia means that the population is too afraid to answer pollsters truthfully, and/or supports Putin but without much enthusiasm, such that they will all defect from him once his sorceror's spell is broken, and the mind-control Towers of Saraksh crumble. (There is also of course an ideological component here as well, namely the unwillingness of Western elites to come to terms with democratic choices that they disapprove of, as has been blatantly demonstrated in the past year by their reactions to Brexit and Trump).

This theory, however, has been conclusively debunked by Timothy Frye et al. in 2015, who used a double list experiment - a clever way of gauging attitudes towards a potentially controversial topic without respondents having to answer it directly - to confirm that Putin's approval ratings as measured by mainstream pollsters were accurate to at least within 10 percentage points, and concluded that the "main obstacle at present to the emergence of a widespread opposition movement to Putin is not that Russians are afraid to voice their disapproval of Putin, but that Putin is in fact quite popular."

III

Leonid Bershidsky identifies three reasons why a coup might have better prospects against Putin than against Erdogan.

First, Bershidsky claims that as an "essentially one-party democracy," Russian voters will not be under any great incentive to defend their votes: "Putin's supporters are passive and often dependent on government largesse - which might still be available from whoever tries to depose the president." This is a dangerous assumption for the coup plotters, and as shown above, almost certainly a false one.

Second, Turkey has allowed foreign media to operate widely: "As a result, it wasn't state television but the secularist, private Dogan media group, which owns the CNN Turk TV channel, that put Erdogan on the air first so he could tell the nation he was fighting the coup attempt." Because of course the Western media is well known for its impartiality towards Putin and its absolute respect for democracy. It's not like they've spent the past sixteen years relentlessly smearing Putin and denying the democratic choices of the Russian people.

Third, Bershidsky points out that "vibrant connection to organized religion is another strength of the Erdogan regime." Although Putin has a good relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church, it is true that that nobody is going to come out even if they were to ring their bells. However, Russia does have a means of instantly politically mobilizing its population: "Patriotic" websites and social media.

Within an hour, if not minutes, of a hostile coup, patriotic bloggers such as Nikolay Starikov are going to call their readers out into the streets. So will Sergey Kurginyan's patriotic-Communist "Essence of Time" movement. They will have a huge immediate audience because Internet penetration in Moscow is at 80%, and close to 70% in the rest of Russia.

This is barely mentioned or remembered nowadays, but it is worth mentioning that during the 2011-12 wave of protests, when Putin's approval ratings were at their nadir, the Kurginyanites still managed to pull off the single biggest (counter)protest of that entire electoral cycle, and they did it in the country's most oppositional city at the time.

Even if, at the time of the coup, Putin's approval rating were to drop to a historic low of 50%, that would still leave 16% of Russians whose "Putinism Quotient" is +1 S.D. [Social Desirability] above the average - perhaps, many of the 16% of Russians who today either have or want to acquire a portrait or sculpture of Putin - who are strong Putin supporters and who would spill over into the streets, like the 800,000 Parisians who marched against a Communist revolution and in support of Charles de Gaulle on May 30, 1968.

The 2% of Russians whose PQ is +2 S.D. above the mean - i.e., easily 100,000 Muscovites alone - would be the ones lynching coup sympathizers on the streets and engaging in battles with the Traitor Legions.

And there does exist a group of people, the +3 S.D. types, too embarrassingly fanatical to be overtly associated even for your average Putin supporter, small in percentage terms but nonetheless substantial in absolute numbers, who can more or less fairly be described as Putin cultists:

The path laid by the father is not one of argument with him, but rather argument with the open world laying before us, an argument in which we are together with the father, at one with him," it says. "We don't fight with the power of the father, we share it, we learn the power, we master the power, together with the father we direct its energy toward our present and future.Presumably, they will most certainly not take the coup lying down (unless it's in front of a tank).

This is ultimately all just bell curve dynamics.

It is almost impossible that the Army or any significant portion of the security agencies would support the coupists. The Russian Armed Forces are a mix of conscripts and professionals. Conscripts tend to come from poorer, working-class families - i.e., more patriotic than hipsters who avoid service - and the professional soldiers are self-selected for greater patriotism, as with militaries almost anywhere. As for the generals, as mentioned above, it is hard to see them ditching the reliable Putin they know for an unelected emigre and convicted financial fraudster from Switzerland.

With neither the people nor the Army behind them, the coup will fail. And that is also why it will almost certainly never start.

There are several conceivable ways in which the Putin regime could end prematurely - an accident or assassination, a huge geopolitical defeat, or perhaps a liberalization of the political system that veers out of control - but a coup is not one of them under both the current and most conceivable future circumstances.

Unlikely, IMHO. Loyalty is a rare commodity and the past couple of decades have shown that leaders come and go; they are expendable and populations are fickle. Also he is not that young so, speaking logically and unemotionally, he probably wouldn't be worth saving in terms of average life expectancy.